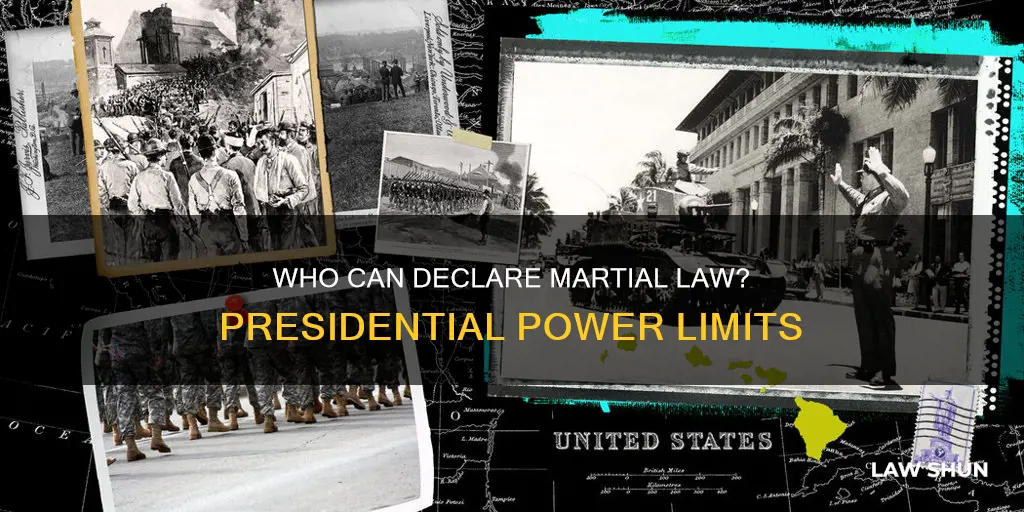

Martial law is a rare occurrence, with no precise definition, and there is little legal precedent for it. It is a dramatic departure from normal practice in the United States, where federal laws usually prevent the military from acting within the country. The US Constitution and founding documents do not mention martial law, nor has Congress passed a law specifying when it can be declared. However, the Constitution's enumerated war powers give both Congress and the president the power to declare martial law. This has been done a number of times in US history, including during times of war, civic dispute, and natural disaster.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can a president call martial law? | The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly state whether or not a president can declare martial law. However, it does not specifically forbid it either. |

| Who can declare martial law? | Both the president and Congress can declare martial law. State officials can also declare martial law, but their actions must abide by the U.S. Constitution. |

| What is martial law? | Martial law is a vague legal term for when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement. During martial law, certain civil liberties may be suspended, and the writ of habeas corpus may be suspended. |

| When can martial law be declared? | Martial law is typically a last resort and is declared in times of extreme emergencies when existing civilian government and law enforcement have ceased to function or become ineffective. |

| Has martial law ever been declared in the U.S.? | Yes, martial law has been declared nine times since World War II, and in five instances, it was used to counter resistance to federal desegregation decrees in the South. |

| What is the Insurrection Act? | The Insurrection Act is a mechanism that allows the president to call upon active-duty troops to enforce the law, not replace it. |

What You'll Learn

The US Constitution and martial law

The US Constitution and its founding documents do not explicitly mention martial law, nor has Congress passed a law specifying when it can be declared. The Constitution also does not explicitly grant the president the power to declare martial law.

The US Constitution's war powers enumerated in Articles I and II give both Congress and the president some control over America's military forces. Article II, Section 2, lists the following presidential powers:

> "The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment."

The commander-in-chief clause establishes that the president is in charge of the army, navy, and state militias. However, the Constitution does not give the president "conclusive and preclusive" authority over the domestic use of the military. Instead, it vests power in the legislative branch, and the president cannot act against Congress's wishes in this area.

The Calling Forth Clause empowers Congress to "provide for" — that is, to regulate and control — the authority and procedures for "calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions." The Guarantee Clause requires the US to "protect each [state] against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence." This language is less clear-cut than the Calling Forth Clause, but it does not grant unilateral power to the executive either. It allows unilateral federal action only in the case of invasion, and in the event of "domestic violence," the affected state must request help before the federal government can act.

The Posse Comitatus Act and other statutes also regulate the domestic use of the military, further limiting the president's ability to declare martial law.

While the president may deploy the National Guard or the regular armed forces to suppress an insurrection or enforce the laws of the United States, this is not the same as declaring martial law. The National Guard assists state and federal governments in enforcing existing laws and must respect the civil rights of all civilians during its deployment.

Martial law is a rare occurrence in the US, and there is limited legal precedent regarding it. It is considered an extraordinary remedy for emergencies and a last resort, as it could be easily abused as a political tool to control the population.

Employment Law: Your Rights & Solutions

You may want to see also

Congress and martial law

The United States Constitution and founding documents do not mention martial law, nor has Congress passed a law specifying when martial law can be declared. The US Constitution also does not explicitly define when a president can declare martial law, although neither does it specifically forbid it. The power to declare martial law is a dramatic departure from normal practice in the United States.

The consensus in 1815 was that martial law was simply another term for military law, and that military jurisdiction could extend no further than the armed forces themselves. However, in the early 1840s, former President Andrew Jackson orchestrated a campaign in Congress to refund him the cost of a fine he incurred for relinquishing control of New Orleans back to its civilian government. Congress enacted the refund bill in February 1844, symbolically endorsing Jackson's three-month-long imposition of martial law in New Orleans. This marked the beginning of a shift in how Americans understood martial law.

In 1871, the House version of Section 4 of an act explicitly authorized the president to declare martial law, but this language was removed before the bill was sent to the Senate. This demonstrates that Congress was aware of martial law and either chose not to authorize it or determined that it lacked the power to do so.

According to national security law scholar Joseph Nunn, martial law turns the relationship between the military and local governments on its head. When the federal or state governments declare martial law, they suspend all local laws, civil authority, and sometimes local judiciaries. In their place, the commanding officer substitutes temporary laws and military tribunals, giving the military commander virtually unlimited authority to govern an area.

While the president is the Commander in Chief of the Army, Navy, and state militias, the Calling Forth Clause empowers Congress to regulate and control the authority and procedures for "calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions." The Guarantee Clause also grants authority to the federal government as a whole and only allows unilateral federal action in the case of invasion.

In almost all states, the governor has the power to impose martial law within the borders of the state, a power given to them by the state constitution or the state legislature. State officials do have the power to declare martial law, but their actions under the declaration must abide by the US Constitution and are subject to review in federal court.

Congress might be able to authorize a presidential declaration of martial law, but this has not been conclusively decided. Congress does always have the right to impeach a president for an abuse of power.

Laws Within Laws: State Sovereignty Examined

You may want to see also

State officials and martial law

State officials have historically declared martial law in the United States, although it is a rare occurrence. The U.S. Constitution and founding documents do not mention martial law, nor has Congress passed a law specifying when it can be declared. The term "martial law" refers to when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement, typically as a last resort during times of extreme emergencies. In such cases, the executive or military leaders may suspend certain civil liberties.

State governors have declared martial law during times of labor unrest, although not in recent years. For example, in 1933, Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge declared martial law to force out some commissioners of the state Highway Board, whom he had no legal power to remove. In 1931, the governor of Texas declared martial law in parts of East Texas due to what he called an insurrection. The military enforced oil production limits in the affected counties.

State militias have also been used to enforce martial law. In the West Virginia Coal Wars (1920-1921), federal troops were dispatched to Mingo County to deal with striking miners. The army officer in charge jailed union miners without any sort of trial. In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked the Insurrection Act to enforce desegregation in Arkansas, but martial law was not declared.

The exact scope and limits of martial law remain unclear, and the Supreme Court precedent is too old, sparse, and inconsistent to provide certainty. Congress and state legislatures need to enact new laws to better define the scope and limits of martial law.

Law Firm Structure: LLC in New York?

You may want to see also

The Insurrection Act

The Act consists of several sections, each designed for a different set of situations. Section 251 allows the president to deploy troops upon the request of a state's legislature or governor if the legislature cannot be convened, to address an insurrection against that state. Section 252 enables the president to deploy troops without a request from the affected state, even against its wishes, to enforce US laws or suppress rebellion when "unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblies" prevent the law from being carried out. Section 253 addresses situations of insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy in any state, resulting in the deprivation of constitutionally secured rights, where the state is unable or unwilling to protect those rights.

While the Insurrection Act grants the president significant authority to deploy US military forces domestically, it has been criticised for its lack of clear definitions and limitations. The Act fails to define key terms such as "insurrection," "rebellion," and "domestic violence," leaving their interpretation up to the president's discretion. This ambiguity has raised concerns about the potential for abuse and the consolidation of federal power.

Stepparent Tax Claims: Can You Claim Your Stepchild?

You may want to see also

Martial law and civil liberties

Martial law is a somewhat vague legal term for when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement. During martial law, the executive or military leaders may suspend certain civil liberties. It is intended to be reserved for times of extreme emergencies when existing civilian government and law enforcement have ceased to function or become ineffective. Typically, the imposition of martial law accompanies curfews, the suspension of civil law, civil rights, and habeas corpus, and the application or extension of military law or military justice to civilians. Civilians defying martial law may be subjected to military tribunals.

In the United States, the Constitution does not explicitly grant the president the power to declare martial law. However, the Constitution's enumerated war powers of the legislative and executive branches give both Congress and the president some control over America's military forces. The president is the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Navy, and state militias. The Calling Forth Clause empowers Congress to regulate and control the authority and procedures for "calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections, and repel Invasions." The Guarantee Clause requires the United States to protect each state against invasion and, upon request, aid the state in addressing domestic violence.

While the president may lack the unilateral authority to declare martial law, Congress might be able to authorize a presidential declaration of martial law. Additionally, in certain circumstances, the president may deploy troops without a request from a state, even against the state's wishes, to enforce the laws of the United States or suppress rebellion. This deployment of troops does not constitute a declaration of martial law, and the troops must respect the civil rights of all civilians during their deployment.

Historically, martial law has been imposed in the United States during the Civil War, the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era, and in limited, local areas during instances of war or invasion, insurrection, civil unrest, labor disputes, natural disasters, and other emergencies. The imposition of martial law has often been controversial, and there is sparse and confusing legal precedent regarding this area.

LLB in England: Practicing Law in the US?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US Constitution does not explicitly grant the president the power to declare martial law, nor does it forbid it. There is no precise definition of martial law, but it generally refers to when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement, and certain civil liberties are suspended.

There have been a limited number of times when martial law has been declared in the US, including during the Civil War, when it was Congressionally-imposed on President Abraham Lincoln. In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked the Insurrection Act to enforce desegregation in Arkansas, but martial law was not declared. In 1931, the governor of Texas declared martial law in parts of East Texas due to what he called an insurrection.

The Insurrection Act is a mechanism that allows the President to employ the National Guard or the regular armed forces to enforce the law and suppress insurrection or civil unrest. It is not the same as declaring martial law.

Congress has the right to impeach a president for an abuse of power, including if a president were to declare martial law without cause. Congress also has the power to pass laws specifying when martial law can be declared, but it has not done so.