The US Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it specify when a president can declare it. However, it does grant Congress the power to impeach the president for abuse of power. Given the ambiguity surrounding the term martial law and the president's extensive authority to deploy the military domestically, it is unclear whether a president could declare martial law if being impeached.

What You'll Learn

- Martial law is a vague term for when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement

- The US Constitution does not define martial law or specify when it can be declared

- Congress has the power to impeach a president for abuse of power

- The Insurrection Act allows the president to deploy troops to suppress insurrection

- Martial law has been used in response to domestic issues, but it is a last resort

Martial law is a vague term for when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement

Martial law is a somewhat vague term for when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement. It is a "dramatic departure from normal practice in the United States", as federal laws usually prevent the military from acting within the country. The US Constitution and founding documents do not mention martial law, nor has Congress passed a law specifying when it can be declared. The Constitution does, however, give Congress the power to declare war and to raise, support and govern armies.

The US President is the Commander-in-Chief of the US Army, Navy, and state militias. This role gives the President the power to call the military into action to help local governments after a natural disaster, for example, or to enforce the law in response to domestic problems. However, this does not amount to declaring martial law. The Posse Comitatus Act, passed by Congress in 1878, prevents the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities.

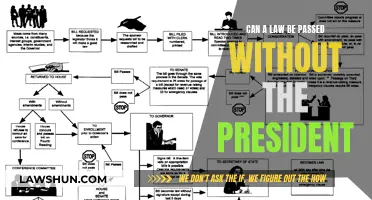

There is no clear answer as to what actions Congress or US citizens could take if a President were to declare martial law without cause. However, Congress does have the right to impeach a President for an abuse of power. Impeachment is an important check on the Executive and Judicial Branches, and Congress has sole power over impeachment.

In the absence of legislation specifically addressing martial law, the exact scope and limits of the term remain unclear. This lack of clarity could lead to confusion and competing interpretations, which could be abused as a political tool to control the population.

Understanding Florida's Trust Garnishment Laws

You may want to see also

The US Constitution does not define martial law or specify when it can be declared

However, the Posse Comitatus Act, enacted by Congress in 1878, prevents the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities. This act restricts the president's ability to use the military for domestic purposes. Additionally, the Insurrection Act allows the president to deploy the National Guard or the armed forces to suppress an insurrection in a state upon the request of its legislature or governor. While this deployment of troops may resemble martial law, it is not the same as declaring martial law, as the National Guard assists in enforcing existing laws without creating or enforcing its own.

The lack of a clear definition of martial law and its limits in the Constitution has led to confusion and varying interpretations. The term has evolved over time, and its use throughout history has defined its application. Generally, martial law refers to when the military temporarily replaces civilian authority and imposes its own rules. It is considered a dramatic departure from normal practice and is intended as a last resort for extreme emergencies when civilian government and law enforcement have ceased to function effectively.

While the president has the power to call on the military for support, the absence of specific legislation addressing martial law leaves room for competing interpretations. The exact scope and limits of martial law remain unclear until Congress and state legislatures enact laws to better define them. Congress has the power to impeach a president for abuse of power, but it is unclear what actions they could take if a president were to declare martial law without cause.

Is It Possible to Pass a Law Targeting One Company?

You may want to see also

Congress has the power to impeach a president for abuse of power

The United States Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it explicitly state when a president can declare it. However, it does grant Congress the power to impeach a president for abuse of power. While the president is the Commander-in-Chief of the US military, Congress also has war powers that act as checks on the president's authority.

Congress, comprised of the House of Representatives and the Senate, has the sole power of impeachment. The House of Representatives charges an official of the federal government by approving, through a simple majority vote, articles of impeachment. The Senate then sits as a High Court of Impeachment to consider evidence, hear witnesses, and vote to acquit or convict the impeached official. A two-thirds vote of the Senate is required for conviction, and the penalty for an impeached official is removal from office and possibly a bar from holding future office.

The impeachment process is a crucial tool for holding government officials accountable for violations of the law and abuses of power. It acts as a check on the Executive and Judicial Branches, helping to prevent the centralization of political power in Congress and ensuring the independence of the separate branches of government.

While the president can declare martial law, it is considered a dramatic departure from normal practice and is typically a last resort. Martial law refers to when the military temporarily substitutes its authority for civilian authority, which can easily be abused as a political tool to control the population. Congress has passed laws, such as the Posse Comitatus Act, to prevent the military from acting within the country and participating in civilian law enforcement activities.

Reselling Lemon Law Cars: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

The Insurrection Act allows the president to deploy troops to suppress insurrection

The United States Constitution and founding documents do not mention martial law, nor has Congress passed a law specifying when martial law can be declared. The Constitution's enumerated war powers give both Congress and the president the power to declare martial law. Articles I and II of the Constitution give each branch some control over America's military forces. The Insurrection Act of 1807 is a United States federal law that empowers the president to deploy troops within the United States in certain circumstances, such as to suppress civil disorder, insurrection, or rebellion. The Act provides a "statutory exception" to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, which limits the use of military personnel for law enforcement purposes within the United States.

The Insurrection Act has been invoked many times throughout American history. President Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked the Act to enforce desegregation in Arkansas in 1957. In 1992, the Act was invoked to control civilian violence and public unrest following a controversial case in Los Angeles. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was invoked during labor conflicts. Later in the 20th century, it was used to enforce federally mandated desegregation, with Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy invoking the Act in opposition to the affected states' political leaders to enforce court-ordered desegregation. In 2006, the George W. Bush administration considered intervening in Louisiana's response to Hurricane Katrina, but this was inconsistent with past precedent, politically difficult, and potentially unconstitutional. On June 1, 2020, President Donald Trump warned that he would invoke the Act in response to the George Floyd protests.

Troops can be deployed under three sections of the Insurrection Act. Each of these sections is designed for a different set of situations. Section 251 allows the president to deploy troops if a state’s legislature (or governor if the legislature is unavailable) requests federal aid to suppress an insurrection in that state. While Section 251 requires state consent, Sections 252 and 253 allow the president to deploy troops without a request from the affected state, even against the state’s wishes. The second part of Section 253 permits the president to deploy troops to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” in a state that “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.” The law's requirements are poorly explained and leave much up to the discretion of the president.

Federal Law vs State Law: Who Wins?

You may want to see also

Martial law has been used in response to domestic issues, but it is a last resort

In the United States, martial law has been used in response to domestic issues, but it is generally considered a last resort. The US Constitution and founding documents do not explicitly define martial law, nor do they specify when it can be declared. However, it is generally understood as a temporary situation in which the military assumes authority over civilian governance and law enforcement, and certain civil liberties may be suspended.

Historically, martial law has been invoked in the US during times of war, invasion, domestic conflict, insurrection, civil unrest, labour disputes, natural disasters, and other emergencies. For example, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared martial law in Hawaii after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and President Abraham Lincoln invoked it during the Civil War with congressional approval. In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked the Insurrection Act, a federal law that allows the use of military forces for law enforcement, to enforce desegregation in Arkansas. In 1992, the Insurrection Act was again invoked to address civilian violence and unrest in Los Angeles following the acquittal of police officers involved in the beating of Rodney King.

While the President is considered the Commander-in-Chief of the military and has the power to call upon the military in certain situations, the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 prevents the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities without congressional approval. This act limits the President's ability to declare martial law. Additionally, the Supreme Court has ruled on cases involving martial law, establishing that trying civilians in military tribunals is unconstitutional when civilian courts are available.

Although the President can call upon the military to assist local governments in emergencies or after natural disasters, this does not constitute a declaration of martial law. Such a declaration is considered a last resort due to the potential for abuse as a political tool to control the population, particularly those expressing dissent. The power to declare martial law is not explicitly granted in the US Constitution, and Congress, as the legislative branch, has the authority to impeach a President for abusing their power.

Jeopardy Law: Can States Change Double Jeopardy Clause?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The US Constitution does not explicitly state whether a president can declare martial law, nor does it forbid it. The Constitution also does not define martial law. However, it is generally understood that the president can call martial law to some degree, as several presidents have done so throughout history.

Martial law is a vague legal term referring to when the military temporarily takes over a civilian area and imposes its own rules, displacing civilian government. It is intended to be reserved for times of extreme emergencies when existing civilian government and law enforcement have ceased to function or become ineffective.

Congress has the right to impeach a president for an abuse of power. However, it is not clear what actions Congress or US citizens could take if a president were to declare martial law without cause, and it would likely depend on the circumstances.

Two federal laws impact the president's ability to declare martial law: the Posse Comitatus Act, which prevents the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities, and the Insurrection Act, which allows the president to deploy troops to suppress an insurrection.