The question of whether a state can enforce a federally non-enforced law is a complex one, involving the interplay between state and federal power. While federal law is typically enforced by federal agencies, there are instances where state enforcement comes into play. In certain cases, the Supreme Court has ruled that state courts must hear federal law claims unless state law explicitly bars it through a neutral rule of judicial administration. However, in other cases, the Supreme Court has upheld state courts' refusal to hear federal claims, finding that state law provided a valid excuse to decline jurisdiction. This dynamic showcases the unique model of enforcement and state power in the US legal system, where states can exert influence by adjusting the intensity of enforcement and interpreting federal law.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| State enforcement of federal law | A unique model of enforcement and a unique form of state power |

| State enforcement authority | Can thrive even in areas where state law is preempted or state regulators have chosen not to act |

| Federal law enforcement | Through a combination of public and private efforts |

| Federal civil statutes | Vest enforcement authority in a federal agency |

| Federal statutes | Authorize civil enforcement by both a federal agency and the states |

| State enforcement | Largely decentralized |

| State courts | Must hear federal law claims unless state law bars a state court from hearing a federal claim through a “neutral rule of judicial administration” that does not improperly burden claims arising under federal law |

| State court enforcement of federal law | Related to, but distinct from, the anti-commandeering doctrine |

What You'll Learn

State court enforcement of federal law

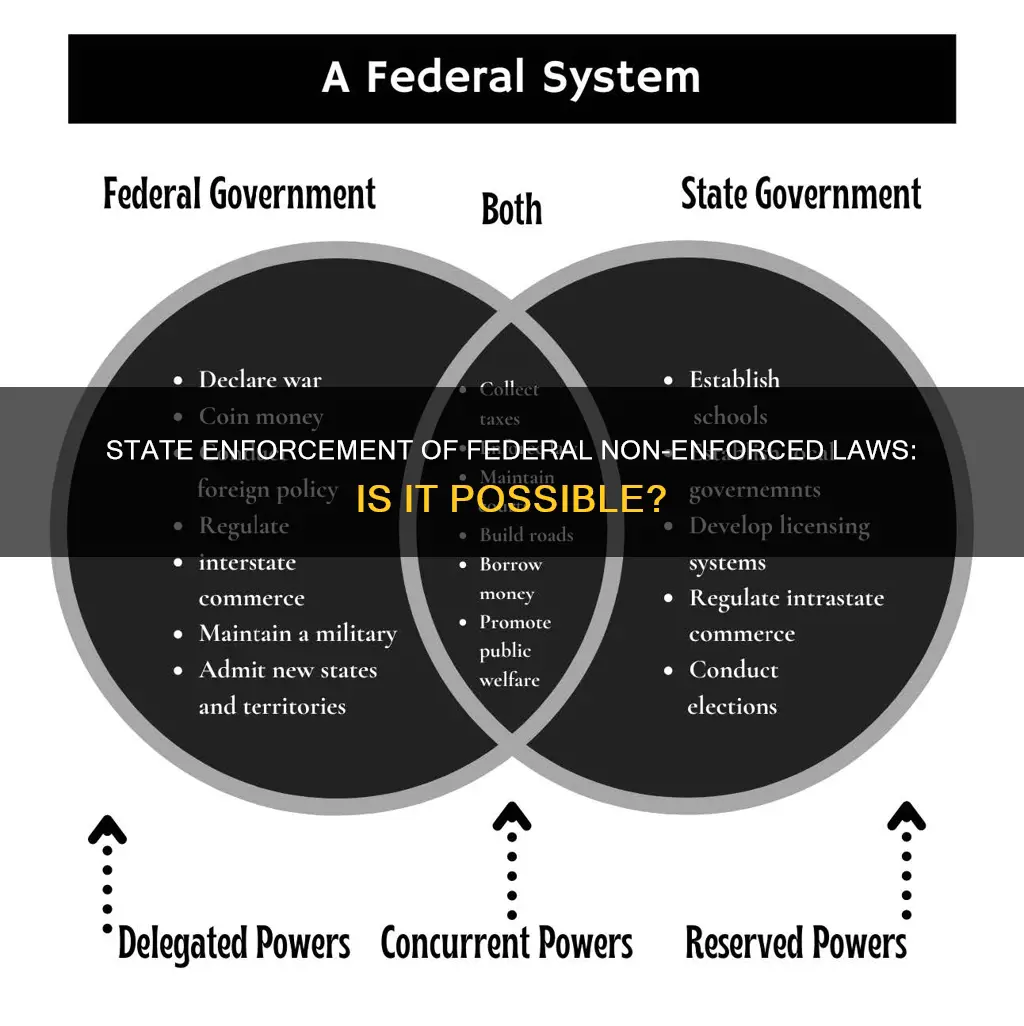

The US Constitution's Vesting Clause gives judicial power to the Supreme Court and other inferior courts ordained by Congress. While states' rights proponents initially wished to leave the enforcement of federal law and rights to state courts, the creation of inferior federal courts shifted this dynamic. This has resulted in a complex interplay between state and federal courts in enforcing federal law.

In the case of Claflin v. Houseman (1876), the Supreme Court held that state courts could hear cases arising under federal bankruptcy law, demonstrating concurrent jurisdiction. However, the Court also indicated that states could not be compelled to enforce federal law, as seen in cases involving the Fugitive Slave Law. Over time, Congress resumed practices that gave state courts concurrent jurisdiction, as seen in the Federal Employers' Liability Act (FELA), which prohibited the removal of cases from state to federal courts.

The Supreme Court has ruled that state courts must generally hear federal law claims unless state law provides a "valid excuse" through a neutral rule of judicial administration that does not burden federal law claims. This was seen in cases like Douglas v. New York, where state law allowed courts to decline jurisdiction over claims when neither party was a state resident. However, in Testa v. Katt (1947), the Court held that state courts must enforce penal laws of the US, even if the state policy was against enforcing such laws of other sovereigns.

The anti-commandeering doctrine further complicates the issue, and federal civil statutes often vest enforcement authority in federal agencies, with some allowing private parties to sue to enforce federal law. State enforcement of federal law gives states the ability to influence and interpret federal laws, even when state law is preempted or state regulators choose not to act.

Law Firms: Client Data Privacy and Security

You may want to see also

State enforcement of federal law as a unique form of state power

State enforcement of federal law is a unique form of state power. This enforcement authority is a potent means of state influence, allowing states to adjust enforcement intensity and interpret federal law in their own way. Notably, enforcement authority is distinct from regulatory authority, and state enforcement of federal law separates these two powers by authorising state actors to enforce the laws of a different sovereign. This means that state enforcement authority can exist independently of state regulatory authority.

In the US, federal law is enforced through a combination of public and private efforts. Federal civil statutes typically vest enforcement authority in a federal agency, but they may also allow private parties to sue to enforce federal law. There are two types of public enforcement: civil enforcement by a federal agency and civil enforcement by the states, usually through their attorneys general. State enforcement is decentralised, and states act on behalf of interests that differ significantly from those of federal enforcers.

The US Supreme Court has ruled that state courts must generally hear federal law claims unless state law bars a state court from hearing a federal claim through a "neutral rule of judicial administration" that does not improperly burden federal claims. For example, in the 1876 case of Claflin v. Houseman, the Supreme Court held that state courts could hear cases arising under federal bankruptcy law. However, in several cases, the Supreme Court has also upheld state courts' refusal to hear federal claims, finding that state law provided a "valid excuse" to decline jurisdiction. For instance, in Douglas v. New York, N.H. & H.R. Co., the Court upheld a state law that allowed state courts to decline jurisdiction over both state and federal law claims when neither party was a resident of the state.

In the case of Testa v. Katt, the Rhode Island Supreme Court initially declined to enforce a federal statute containing a punitive damages provision, deeming it penal in nature and not a responsibility of the state to enforce. However, the US Supreme Court reversed this decision, holding that the Rhode Island court must enforce the federal statute and that a state policy of not enforcing penal statutes of other sovereigns was not a valid excuse.

Martial Law: Can Trump Declare It?

You may want to see also

Public and private enforcement

Federal law in the United States is enforced through a combination of public and private efforts. Virtually all federal civil statutes vest enforcement authority in a federal agency, and some also create private rights of action that allow private parties to sue to enforce federal law. There are two distinct types of public enforcement: civil enforcement by a federal agency and civil enforcement by the states, typically through their attorneys general.

State enforcement of federal law is a unique form of state power. Enforcement authority can be a potent means of state influence, enabling states to adjust the intensity of enforcement and to press their own interpretations of federal law. State enforcement authority can thrive even in areas where state law is preempted or state regulators have chosen not to act. For example, in the 1876 case of Claflin v. Houseman, the Supreme Court held that state courts could hear cases arising under federal bankruptcy law.

In several cases, the Supreme Court has ruled that state courts must hear federal law claims unless state law bars a state court from hearing a federal claim through a "neutral rule of judicial administration" that does not improperly burden claims arising under federal law. However, the Supreme Court has also upheld state courts' refusal to hear federal claims in certain circumstances, finding that state law provided a "valid excuse" to decline jurisdiction.

Private law enforcement in the United States is a significant force, with over 1.05 million people employed as private law enforcement officers as of 2014. Private law enforcement can be instituted in a range of ways, from traditional security guards with a limited scope to officers with more extensive powers. Private citizens in the United States have the authority to arrest, search, carry weapons, interrogate, and detain persons suspected of certain crimes, although this also comes with certain liabilities. Private officers could be assigned to mitigate threats in areas with high property crime rates, while more trained and experienced public officers could focus on more serious hotspots.

Informants: Breaking Law, Confidentiality, and Ethical Boundaries

You may want to see also

State court refusal to hear federal claims

In the United States, state courts have both the power and the duty to enforce federal law unless federal courts have been given exclusive jurisdiction. State courts are bound to give effect to federal law and disregard state law when there is a conflict.

In several cases, the Supreme Court has upheld state courts' refusal to hear federal claims, finding that state law provided a "valid excuse" to decline jurisdiction. For example, in Douglas v. New York, N.H. & H.R. Co., the Court upheld a state law that allowed state courts to decline jurisdiction over both state and federal law claims when neither party was a resident of the state.

In the 2009 case Haywood v. Drown, the Supreme Court considered a state statute that divested New York state courts of jurisdiction over suits seeking money damages from corrections officers. The Court held that the New York law violated the Supremacy Clause, emphasizing that only a neutral jurisdictional rule would be deemed a "valid excuse" for departing from the assumption that state courts will hear federal claims.

In McKnett v. St. Louis & S.F. Ry., the Federal Constitution prohibited state courts of general jurisdiction from refusing to hear federal claims solely because the suit arose under federal law. Similarly, in Testa v. Katt, the Rhode Island Supreme Court declined to enforce a federal statute containing a punitive damages provision, but the U.S. Supreme Court reversed this decision, holding that the Rhode Island court must enforce the federal statute.

In summary, while state courts generally have a duty to enforce federal law, there may be limited circumstances where they can decline jurisdiction based on valid excuses provided by state law or neutral rules of judicial administration that do not improperly burden federal claims.

Cloud-Based Cameras: Admissible Court Evidence?

You may want to see also

State enforcement of federal law when state law is preempted

The US Constitution establishes federal law as "the supreme law of the land". This means that when a federal law conflicts with a state or local law, the federal law takes precedence and supersedes the other law(s). This is known as "preemption".

However, the preemption doctrine is not always straightforward in practice. Determining whether federal law preempts state law requires an extensive analysis. While Congress can include specific language in a statute that preempts state law, even in the absence of such language, preemption could be implied by other factors.

The Supreme Court has established requirements for preemption of state law and has identified ways to determine whether Congress intended federal law to preempt state law. In Altria Group v. Good, the Supreme Court described the preemption doctrine and cautioned that, when evaluating evidence of Congressional intent, courts should err on the side of state rather than federal authority.

In several cases, the Supreme Court has upheld state courts' refusal to hear federal claims, finding that state law provided a "valid excuse" to decline jurisdiction. For example, in Douglas v. New York, N.H. & H.R. Co., the Court upheld a state law that allowed state courts to decline jurisdiction over both state and federal law claims when neither party was a resident of the state.

Despite the preemption doctrine, state enforcement of federal law can still occur. Enforcement authority can serve as a potent means of state influence, enabling states to adjust the intensity of enforcement and to press their own interpretations of federal law. State enforcement of federal law authorises state actors to enforce the laws of a different sovereign, allowing state enforcement authority to thrive even in areas where state law is preempted or state regulators have chosen not to act.

Common Law vs Federal Statutes: Who Wins?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In several cases, the Supreme Court has upheld state courts' refusal to hear federal claims, finding that state law provided a "valid excuse" to decline jurisdiction. For example, in Douglas v. New York, N.H. & H.R. Co., the Court upheld a state law that allowed state courts to decline jurisdiction over both state and federal law claims when neither party was a resident of the state.

State enforcement of federal law is a unique model of enforcement and a unique form of state power. Enforcement authority can serve as a means for states to exert influence, enabling them to adjust the intensity of enforcement and interpret federal law. State enforcement of federal law authorizes state actors to enforce the laws of a different sovereign.

Federal law is enforced through a combination of public and private efforts. Federal civil statutes typically vest enforcement authority in a federal agency, and some also allow private parties to sue to enforce federal law. State enforcement is decentralized, and states act on behalf of interests that may differ from those of federal enforcers.