The Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provides the basic rule regarding the acquisition of citizenship of the United States and confers state citizenship on national citizens who reside in a state. The Amendment does not, however, address the rights that come with this status. Before the Amendment, the Constitution recognized both state and national citizenship. The question of whether a state may confer state citizenship on anyone who is not a citizen of the United States remains open. The Equal Protection Clause protects the rights of non-citizens to some extent, and federal statutes prohibit conspiracies to deprive any person of rights or privileges secured by state laws.

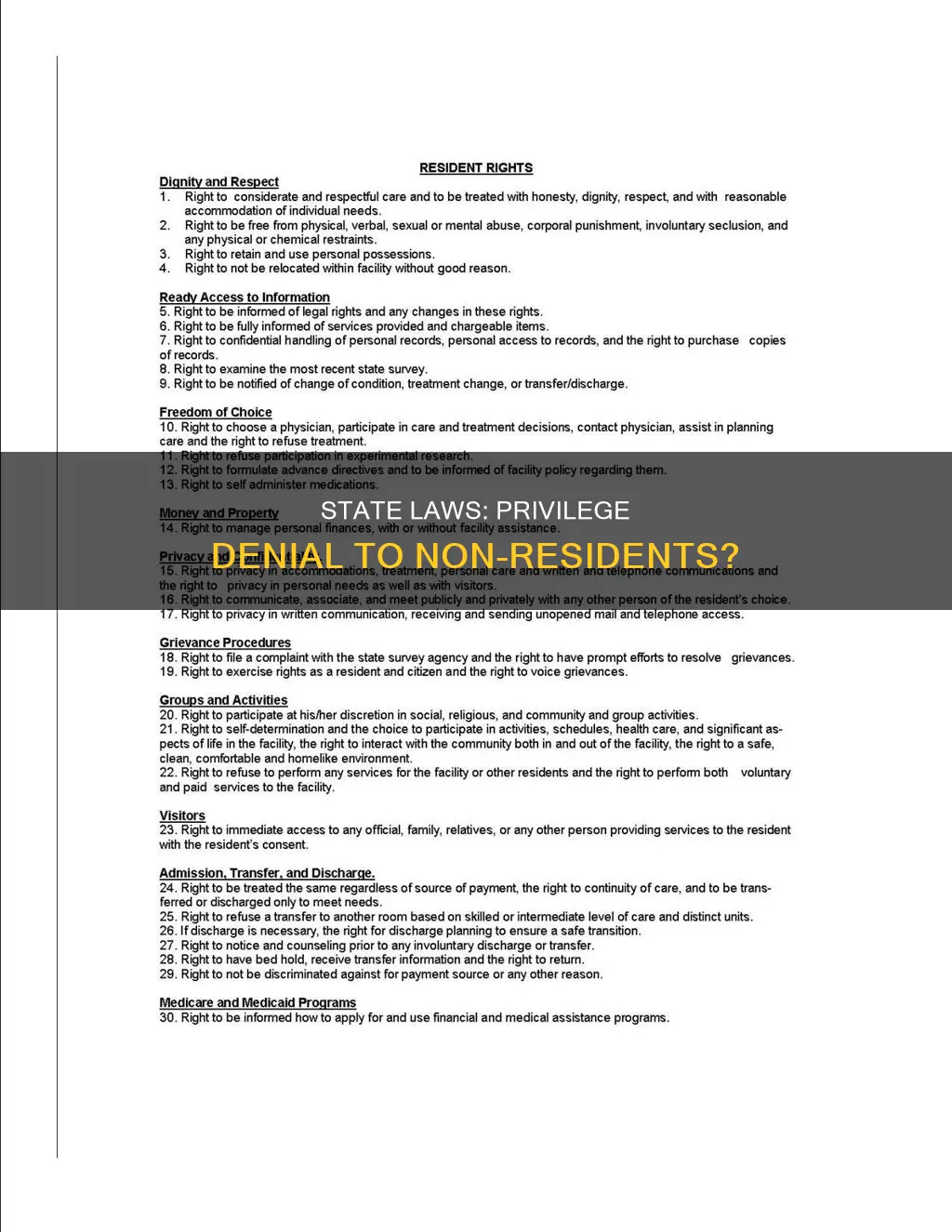

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can a state deny privileges to non-residents? | No, the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment states that no state can make or enforce any law that abridges the privileges or immunities of US citizens. |

| Can a state deny privileges to citizens of another state? | No, the Fourteenth Amendment also states that citizens of one state who are visiting another state are entitled to the "Privileges and Immunities" of citizens of the latter state. |

| Can a state deny privileges to new residents? | No, the Fourteenth Amendment affirms that a new arrival to a state is entitled to the same rights and benefits as other state citizens. |

| Can a state deny privileges to citizens who have not met durational residency requirements? | Yes, state laws that distinguish between citizens based on how long they have been in the state are evaluated under the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. |

What You'll Learn

The Fourteenth Amendment

The Amendment also guarantees the right of US citizens to choose their state of residence, as seen in Saenz v. Roe, where the Court found that a California law restricting welfare benefits for new residents violated the right of new citizens to be treated equally.

The "equal protection of the laws" is another important aspect of the Fourteenth Amendment. This phrase has been frequently litigated in landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education (racial discrimination) and Roe v. Wade (reproductive rights).

Faraday's Law: Understanding the Underlying Principles and Derivations

You may want to see also

Citizenship Clause

The Citizenship Clause, or the Fourteenth Amendment, states that:

> All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Citizenship Clause was added to the United States Constitution on July 9, 1868, as a response to the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, which had declared that African Americans were not and could not become citizens of the United States. The Clause was also a response to Senator Benjamin Wade's concern that the question of citizenship was "settled by the civil rights bill". The Civil Rights Act of 1866, which was the first action in this matter, declared that all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power were citizens of the United States. However, the Act excluded "Indians not taxed" and persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers".

The Citizenship Clause also reversed the concept of citizenship decided by the Supreme Court, which held that United States citizenship was enjoyed by only two classes of people: white persons born in the United States as descendants of persons who were citizens at the time of the Constitution's adoption, and those who were born outside the dominions of the United States but had migrated and been naturalized therein.

The Citizenship Clause has been interpreted to mean that a child born in the United States to Chinese parents who were ineligible for naturalization is nevertheless a citizen of the United States entitled to all the rights and privileges of citizenship. This interpretation was affirmed in the case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark, which restored the traditional precepts of citizenship by birth.

Congressional Power: Overturning Supreme Court Rulings?

You may want to see also

State vs national citizenship

The concept of state citizenship versus national citizenship has been a subject of debate and controversy throughout US history, with the original Constitution not providing a clear and comprehensive rule about either form of citizenship.

State citizenship was of great importance, as it granted access to federal courts and secured rights for citizens of one state while they were present in another. However, the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857 brought the issue of citizenship into sharp focus. Dred Scott, a slave who had been taken by his master into free territory, sued his master's estate, seeking a determination that he had become free. The Court's decision, which stated that Scott was not a citizen of any state and that the Constitution limited citizenship on racial grounds, was strongly disputed. This controversy played out against the backdrop of the Civil War and the debate over slavery, with the Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, ultimately winning control of the White House and taking a legal position opposing the Court's ruling.

The Fourteenth Amendment, drafted in the spring of 1866, addressed the issue of citizenship by granting both national and state citizenship, using language similar to the Civil Rights statute. The basic principle of a federal rule of race-blind citizenship based on birth and naturalization was largely undisputed, although there were debates about restricting citizenship to persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

Even today, the distinction between state and national citizenship remains relevant. For example, in the context of residency and legal residence, an individual's status as a resident or legal resident of a particular state can have significant implications for the enforcement of commercial law statutes and taxation. Additionally, while US nationals enjoy many of the same benefits as citizens, such as the right to travel, live, and work in the country, they cannot participate in certain government activities like voting or serving unless they go through the naturalization process to become full citizens.

Abortion Laws: State-by-State Differences and Their Impact

You may want to see also

The right to travel

Under the US Constitution, the right to travel includes three key components. Firstly, it protects the right of citizens to move freely between states, a right that has been long-standing but lacks a clear doctrinal basis. Secondly, it guarantees that citizens of one state who are temporarily visiting another state are entitled to the same "Privileges and Immunities" as citizens of the latter state. This provision, outlined in Article IV of the Constitution, ensures that state governments must treat all American citizens equally, regardless of their residency status. Lastly, the right to travel protects the right of new arrivals to a state to enjoy the same rights and benefits as other citizens of that state. This component is often invoked in challenges to durational residency requirements, which mandate that individuals must reside in a state for a specified period before accessing certain benefits or privileges.

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in interpreting and upholding the right to travel. In Crandall v. Nevada (1868), the Court affirmed that freedom of movement is a fundamental right, prohibiting states from imposing taxes that inhibit people from leaving. The Court further explored the right to travel in United States v. Wheeler (1920), where it reiterated that the Constitution does not grant the federal government the power to protect freedom of movement. However, the Wheeler decision also located the right to travel within the "Privileges and Immunities" clause, providing it with stronger constitutional protection.

While the right to travel is well-established, there are still unresolved issues and exceptions to this freedom. For example, durational residency requirements for occupational licenses and certain government benefits remain contentious. Additionally, restrictions on freedom of movement have been imposed as a punishment for child support debtors, although these measures have faced constitutional challenges.

Internationally, the right to freedom of movement is recognised in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that "everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state". This declaration underscores the importance of ensuring that individuals are not arbitrarily denied the ability to travel and establish residence.

Scientific Laws: Infallible or Flexible?

You may want to see also

Durational residency requirements

A durational residency requirement is when someone has to live in a particular place for a specific amount of time before they can do something, like voting or receiving in-state tuition rates at a public university. For example, some states may require that a person must live in the state for at least one year before they can vote in a state election or receive the in-state tuition rates.

While the definition of residency varies by state, generally, residency is defined as presence within the jurisdiction and the intention to be a resident of that jurisdiction. This means that simply being present in a jurisdiction may not be sufficient to establish residency, and one must also intend to make that place their home.

It is important to note that the evaluation of durational residency requirements is complex and fact-specific. What may be considered reasonable and constitutional in one context may not be in another. Each case must be carefully assessed to ensure that individuals' rights are protected while also respecting the state's authority to set certain residency requirements.

Civil Law in Common Law Courts: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No state can deny the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States. However, there are certain privileges that are exclusive to citizens of a particular state.

Privileges that are exclusive to citizens of a particular state include the right to vote and welfare benefits.

The basis for denying privileges to non-residents is often the durational residency requirement, which requires individuals to reside in a state for a specified period before enjoying the benefits of state citizenship.

No. The first sentence of Article IV provides that citizens of one state who are temporarily visiting another state are entitled to the "Privileges and Immunities" of citizens of the latter state.

It depends on the specific circumstances and the individual's status. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment offers some protection to legal aliens, but the extent of this protection is subject to legal interpretation.