The applicability of rules and laws to cases is a complex issue that often arises in the context of legal proceedings. In the state of Florida, the Florida Family Law Rules of Procedure outline the guidelines for handling family law cases, with the aim of simplifying the litigation process for families. These rules are subject to amendments and updates, as seen in Rule 12.015, which was last amended in May 2024. Understanding the retroactive application of laws is crucial, especially when dealing with appeals. While a new law typically applies from the date of its enactment, there are situations where retroactive effect may be considered. The Florida Supreme Court has established a two-pronged test to determine retroactivity, examining legislative intent and constitutional principles. This complex interplay between procedural rules and retroactivity underscores the importance of staying updated with the latest legal developments and seeking expert legal advice when navigating family law matters in Florida.

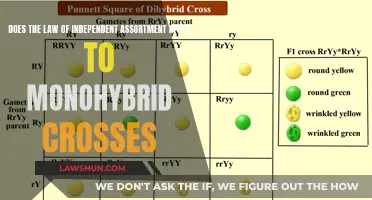

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Florida Supreme Court's two-prong test for determining retroactivity | 1. Whether the legislation clearly expresses an intent that it should apply retroactively; and |

| 2. Whether retroactive application would violate any constitutional principles | |

| Retroactive effect of new law | A new law may not be given retroactive effect, merely because it relates to conduct that predates the statute’s enactment or issuance of an appellate decision |

| Apparent tension | "A court is to apply the law in effect at the time it renders its decision" vs. "retroactivity is not favored in the law" |

| Legislative Intent Concerning Retroactivity | The first prong involves a question of statutory construction which requires that legislative intent be determined from the plain language of the statute |

| A statute that clearly and unambiguously states that it applies retroactively will be given such effect | |

| Unless the legislature expressly and unequivocally announces a contrary intent within the act, substantive legislation is presumed to apply prospectively | |

| Procedural and remedial measures | Procedural and remedial measures are presumed to apply retroactively |

| Substantive measures | Substantive measures either create or impose a new obligation or duty, or impair or destroy existing rights |

| Procedural law | Procedural law concerns the means and methods to apply and enforce those duties and rights |

| Remedial statute | "A remedial statute is one which confers or changes a remedy; a remedy is the means employed in enforcing a right or in redressing an injury" |

| Constitutional Implications of Retroactive Application | Retroactive application is constitutionally permissible if it does not violate due process, e.g., by impairing vested rights, creating new obligations, or imposing new penalties |

What You'll Learn

Legislative Intent and Retroactivity

The Florida Supreme Court has set out a two-prong test to determine whether new statutes or constitutional amendments should be applied retroactively. Firstly, it must be established whether the legislation expresses a clear intent to be applied retroactively. This involves examining the plain language of the statute, where an unambiguous statement of retroactive application will be respected. However, if legislative intent is unclear, certain presumptions come into play. Substantive legislation, which creates or imposes new obligations or duties, or impairs or destroys existing rights, is generally presumed to apply prospectively unless the legislature expressly states otherwise.

On the other hand, procedural and remedial measures are presumed to apply retroactively. Procedural law deals with the means and methods to apply and enforce duties and rights, while remedial statutes confer or change a remedy, or the means to enforce a right or redress an injury. However, even if a statute is remedial, it will not be applied retroactively if doing so would attach new legal consequences to events that occurred before its enactment.

The second prong of the test considers whether retroactive application would violate any constitutional principles. Retroactivity is constitutionally permissible if it does not violate due process, such as by impairing vested rights, creating new obligations, or imposing new penalties. For example, a law that impairs the obligation of contracts or an ex post facto law would raise constitutional concerns.

In summary, when determining the retroactivity of new legislation, it is essential to consider both the legislative intent, based on the statute's plain language, and the potential constitutional implications of applying the law retroactively.

Jim Crow Laws: Hispanics and Their Plight

You may want to see also

Procedural and Remedial Measures

Procedural law concerns the means and methods used to apply and enforce duties and rights. It relates to the admission of evidence and the rules of procedure can be applied retroactively. For example, in Windom v. State, a statute that related to the admission of evidence was considered procedural.

On the other hand, remedial measures are those that confer or change a remedy. A remedy is the means employed to enforce a right or redress an injury. However, it's important to note that Florida courts have not classified statutes that create substantive new rights or impose new legal burdens as remedial legislation that should be applied retroactively. For instance, in L. Ross, Inc. v. R.W. Roberts Const. Co., a statute creating a right to attorney fees could not be applied retroactively.

Therefore, when determining whether a procedural or remedial measure applies retroactively in Florida, it is crucial to consider whether it creates or imposes new obligations, duties, rights, or impairments. Additionally, it is essential to examine the legislative intent behind the measure and whether retroactive application would violate any constitutional principles.

Laws and Regulations for PWC Operators: What You Need Know

You may want to see also

Constitutional Principles

The Florida Supreme Court has set out a two-prong test for determining whether newly enacted statutes or constitutional amendments should be applied retroactively:

- Whether the legislation clearly expresses an intent that it should apply retroactively.

- Whether retroactive application would violate any constitutional principles.

The first prong involves a question of statutory construction, which requires that legislative intent be determined from the plain language of the statute. If the statute clearly and unambiguously states that it applies retroactively, it will be given such effect.

The second prong requires the court to determine whether retroactive application is constitutionally permissible. Retroactive application is constitutionally permissible if it does not violate due process, e.g., by impairing vested rights, creating new obligations, or imposing new penalties.

Family Law Statutes: Civil Cases in California

You may want to see also

Decisional Law

A change in decisional law while a case is pending on appeal may be applied retroactively. This principle is known as the "pipeline rule" and requires that "disposition of a case on appeal should be made in accord with the law in effect at the time of the appellate court's decision rather than the law in effect at the time the judgment appealed was rendered."

Hendeles v. Sanford Auto Auction, Inc. is a case in point. Here, the Florida Supreme Court held that a change in decisional law while a case is pending on appeal should be applied retroactively. This means that the appellate court should apply the law as it stands at the time of the final disposition, rather than the law that was in effect at the time of the original judgment.

This principle was further reinforced in Miami v. Harris, where the court asserted that "it is apodictic that where there is a change in law between the trial of a case and the final disposition of the appeal, the appellate court must apply the law as it exists at the time of final disposition."

The pipeline rule generally applies unless the opinion states otherwise. For example, in Martinez v. Scanlan, the Florida Supreme Court declared a statute void ab initio but pronounced that its "decision shall operate prospectively only." It's important to note that only the Florida Supreme Court possesses the authority to determine whether its decisions should be applied prospectively or retroactively.

In summary, the pipeline rule dictates that a change in decisional law while a case is pending on appeal is typically applied retroactively. However, the Florida Supreme Court holds the exclusive power to determine the prospective or retroactive application of its decisions, as exemplified in the Martinez v. Scanlan case.

Conflict of Interest Laws: Do They Bind the President?

You may want to see also

Statutory Interpretation

When determining the retroactivity of a statute, the Florida Supreme Court employs a two-pronged test. Firstly, it evaluates whether the legislation expresses a clear intent for retroactive application. This involves scrutinising the plain language of the statute to discern legislative intent. If the statute explicitly and unambiguously states its retroactive nature, it will be applied retroactively. However, if the legislative intent is not apparent, certain presumptions come into play. Generally, substantive legislation—which creates or imposes new obligations, duties, or rights—is presumed to apply prospectively unless the legislature expressly announces otherwise. On the other hand, procedural and remedial measures are typically presumed to have retroactive application.

The second prong of the test assesses whether retroactive application would violate any constitutional principles. This analysis focuses on due process considerations, such as whether retroactivity would impair vested rights, create new obligations, or impose new penalties. A law that impairs the obligation of contracts or includes ex post facto provisions would likely raise constitutional concerns.

Additionally, it's important to distinguish between changes in legislation and changes in decisional law while a case is pending on appeal. The "pipeline rule" dictates that a change in decisional law should be applied retroactively to cases on appeal, ensuring that the disposition of a case aligns with the law in effect at the time of the appellate court's decision.

In summary, determining the retroactive application of Florida family law rules of procedure involves interpreting legislative intent, considering presumptions, and evaluating constitutional implications. The Florida Supreme Court's two-pronged test provides a structured framework for this process, ensuring a thorough assessment of retroactivity while upholding constitutional principles and respecting legislative intent.

Stark Law and Its Applicability to Medicaid Patients

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Florida Family Law Rules of Procedure are a set of rules and regulations that govern family law cases in the state of Florida. These rules include procedures for filing, service of process, discovery, and other aspects of family law litigation.

The Florida Family Law Rules of Procedure do not apply retroactively. Any changes to these rules will only apply to cases filed after the effective date of the change. However, if a case is pending on appeal and a new rule is enacted that could affect the outcome of the case, an appellate attorney may discuss the possibility of applying the new rule to the pending case.

The Florida Family Law Rules of Procedure can be found on the Florida Courts website. The website provides links to the different rules of court procedure for Florida courts, including the Florida Family Law Rules of Procedure. Additionally, the website offers resources such as caselaw updates, self-help information, and information for elders related to family law.