Teaching the process of how a bill becomes a law is a fundamental aspect of civics and government education. While the legislative process can be complex and time-consuming, with many minuscule steps, it is important for students to gain a comprehensive understanding of this process. This lesson can be made more engaging by incorporating collaborative activities and providing real-world context. For instance, students can examine the path of a House Resolution through legislation, learning about committees, lobbying, filibusters, and presidential actions. The lesson can also be enhanced by providing visual examples, such as photos of Congress in action or political cartoons, and by examining current legislation to demonstrate how Congress functions in practice.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of bills introduced in Congress that become law | Very few |

| Members of government involved | Members of Congress, the President |

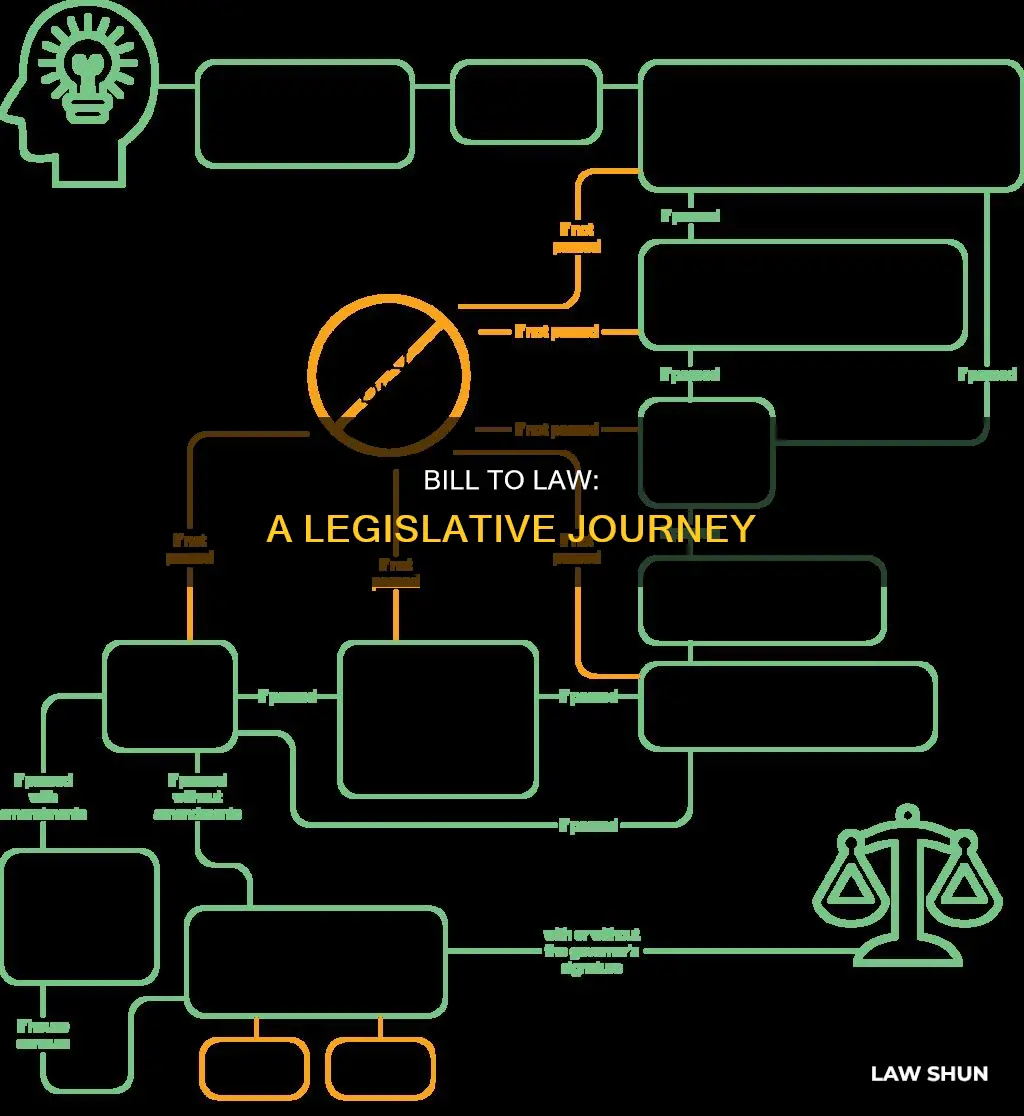

| Legislative process | A bill is drafted and introduced in either the House or the Senate; assigned to a committee; goes to the entire House or Senate for discussion and a vote; if it passes in one chamber, it goes to the other; the two chambers work together to make the bills identical; the single bill goes to the President, who has the power to sign it into law or veto it |

What You'll Learn

The role of the Legislative Branch

The Legislative Branch is a crucial component of the law-making process, and its primary function is to create laws that "provide for the common defence and general welfare" of the American people. This branch is at the heart of a representative democracy, where members of Congress are entrusted to work on behalf of their constituents. Here is a detailed overview of the role of the Legislative Branch:

Drafting and Introducing Bills

The legislative process begins with the drafting and introduction of a bill. This can be done in either the House of Representatives or the Senate, and thousands of bills are introduced in Congress each year. However, only a small fraction of these bills become laws.

Committee Assignments and Examinations

Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee, which plays a critical role in shaping the legislation. The committee closely examines, debates, and refines the bill. This process involves expertise and time, as committee members scrutinise the bill's potential impact and make amendments.

Floor Discussion and Voting

After the committee stage, the bill proceeds to the entire House or Senate for further discussion and voting. This is where the bill is presented to all members of the chamber, who can contribute to the debate and influence their peers' votes.

Bicameral Consideration

If the bill passes in one chamber, it then moves to the other chamber (the Senate or the House) and undergoes the same rigorous process. This bicameral consideration ensures that legislation is reviewed and approved by a diverse group of representatives.

Reconciliation and Finalisation

When a bill passes both chambers, the two chambers work together to reconcile any differences and make the bills identical. This step is crucial in ensuring that the final legislation is consistent and coherent.

Presidential Action

The single, reconciled bill then goes to the President, who has the power to sign it into law or veto it. This step concludes the legislative process, and the bill either becomes a law or is sent back to Congress for further revisions.

The Legislative Branch, through these steps, plays a vital role in translating the needs and desires of the people into laws. It serves as a check and balance in the law-making process, ensuring that legislation undergoes thorough scrutiny and debate before becoming law.

Understanding Riders: How a Bill Becomes a Law

You may want to see also

The life and death of a bill in Congress

The first step is the introduction of the bill, where it is assigned to a committee, and a bill number is given. The committee then reviews the bill and may hold hearings to gather input from experts and the public. After the committee has finished its work, the bill is reported back to the full house, where it is debated and voted on. If the bill passes this vote, it moves to the second house, where the process is repeated. If it fails, the bill is sent back to the drawing board.

Once a bill has passed both houses, it is sent to the president for approval. If the president approves, it becomes law. However, if the president vetoes the bill, it is sent back to Congress, where a two-thirds majority in both houses can still override the veto and pass the bill into law.

It is important to note that any bill that has not become law by the end of a Congress is considered "dead." For such a bill to be enacted, it would need to be reintroduced in the new Congress with a new number, essentially starting the entire legislative process over.

Charles' Law: Gases Transforming into Liquids

You may want to see also

Committees, lobbying, and filibuster

Committees are an essential part of the legislative process, as they are responsible for reviewing and amending bills before they reach the floor for a vote. Lobbying is the act of attempting to influence the decisions of officials and representatives. Filibustering is a tactic used to delay or prevent a vote on a bill by prolonging the debate. These three concepts are interconnected and play a crucial role in how a bill becomes a law.

Committees

Committees are an essential part of the legislative process in the United States. They are usually made up of a group of legislators with specific expertise or interest in the subject matter of the bill. These committees are responsible for reviewing, amending, and refining bills before they reach the floor for a vote. The committee process allows for a more thorough examination of the bill's content, implications, and potential impact. It also provides an opportunity for stakeholders and the public to provide input through hearings and discussions.

Lobbying

Lobbying is the act of attempting to influence the decisions, opinions, or actions of officials and representatives. It is a common practice in politics, where individuals or groups seek to promote their interests, causes, or policies. Lobbying can take many forms, including meeting with legislators, writing letters, or conducting public campaigns. While lobbying can be a legitimate form of political participation, it has sometimes been associated with corruption or undue influence.

Filibuster

A filibuster is a tactic used in legislative bodies, particularly in the United States Senate, to delay or prevent a vote on a bill by prolonging the debate. The term "filibuster" is derived from the Dutch word for "freebooter" and the Spanish "filibusteros," referring to pirates raiding Caribbean islands. It involves senators using long speeches or other dilatory tactics to prevent a vote from taking place. The filibuster has been a key component of the Senate's tradition of unlimited debate and has been both praised and criticised for its impact on the legislative process.

The filibuster has a long history in the US Senate, with the first recorded instance occurring in 1789. Over time, as the number of filibusters grew, the Senate introduced rules to limit this practice, known as "cloture." Initially, invoking cloture required a two-thirds majority vote, but this was later reduced to three-fifths of all senators (60 out of 100). Despite these rules, filibusters continued to be a frequent tactic, especially on controversial issues such as civil rights legislation.

In recent years, the filibuster has faced increasing criticism and attempts at reform, with some arguing that it obstructs the legislative process and prevents important bills from being passed. Others defend it as a protector of political minorities, ensuring that the majority cannot push through legislation without careful consideration and debate. The filibuster remains a significant aspect of the Senate's procedures, shaping the way laws are made in the United States.

The Journey of a Bill to Law

You may want to see also

The President's power to sign or veto

The US President has the power to veto a bill passed by Congress to prevent it from becoming law. The presidential veto is not absolute, however, and Congress can override the veto by a two-thirds vote in both chambers.

Once a bill has passed through both chambers of Congress, it is presented to the President. The President has ten days, excluding Sundays, to sign the bill into law or veto it. If the President does not take any action on the bill within the ten-day period, it becomes law without their signature, unless Congress has adjourned under certain circumstances.

If the President chooses to veto the bill, it is returned to the chamber in which it originated, along with a veto statement outlining the reasons for their disapproval. The chamber can then attempt to override the veto, but this requires a two-thirds majority vote. If this is successful, the bill is sent to the other chamber, which must also vote by a two-thirds majority to override the veto. Only if both chambers agree by a two-thirds majority does the bill become law.

Historically, Congress has overridden presidential vetoes about 7% of the time. The first presidential veto was exercised by George Washington in 1792, and the first successful override of a veto occurred in 1845 during the presidency of John Tyler.

The Lawmaking Process: Senate and House Worksheet Guide

You may want to see also

Examining current legislation

Teaching ideas for how a bill becomes a law are abundant, but lessons often stick to verbalizing the steps and displaying a flowchart. However, there are more creative ways to engage students with this topic.

One way to make the content more relatable is to incorporate current affairs. Teachers can pull up news outlets or official government pages to show students what legislation Congress is currently working on. This strategy demonstrates how Congress functions in real-time, which is often very different from the idealized flowchart model. Teachers can also assign students to read and analyze a news article, or they can bring in a political cartoon or two that depicts current actions and attitudes about Congress.

Another idea is to have students examine a House Resolution from the 116th Congress and follow its path through legislation. They can learn about committees, lobbying, filibusters, and presidential actions.

A third strategy is to use visual examples. Teachers can include photos and visuals of Congress in action with recent or landmark laws in their lecture slides. For instance, a photo of the President at the State of the Union Address telling Congress about the laws they want to see enacted.

Teachers can also have students examine the Constitutional wording. They can give students the text of Article I, Section 7, where the basic process of lawmaking is outlined.

Understanding How Proposals Become Law

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Any member of the House of Representatives can introduce a bill. In the Senate, members must gain recognition from the presiding officer to announce the introduction of a bill during the morning hour.

The bill must be approved by the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the President. The bill is first proposed, then introduced, and then goes to committee. After being reported, it is debated, voted on, and, if passed, referred to the Senate. If it passes in the Senate, it is sent to the President. If the President approves, it becomes a law.

The President has three options: they can sign and pass the bill, refuse to sign or veto it, or do nothing (pocket veto). If they veto the bill, it is sent back to the House of Representatives with their reasons for the veto. If two-thirds of the Representatives and Senators still support the bill, the veto can be overridden, and the bill becomes a law.

Congress's primary function as the Legislative Branch of the US government is to create and modify laws. They have the authority to levy and collect taxes and provide for the common defence and welfare of the United States.