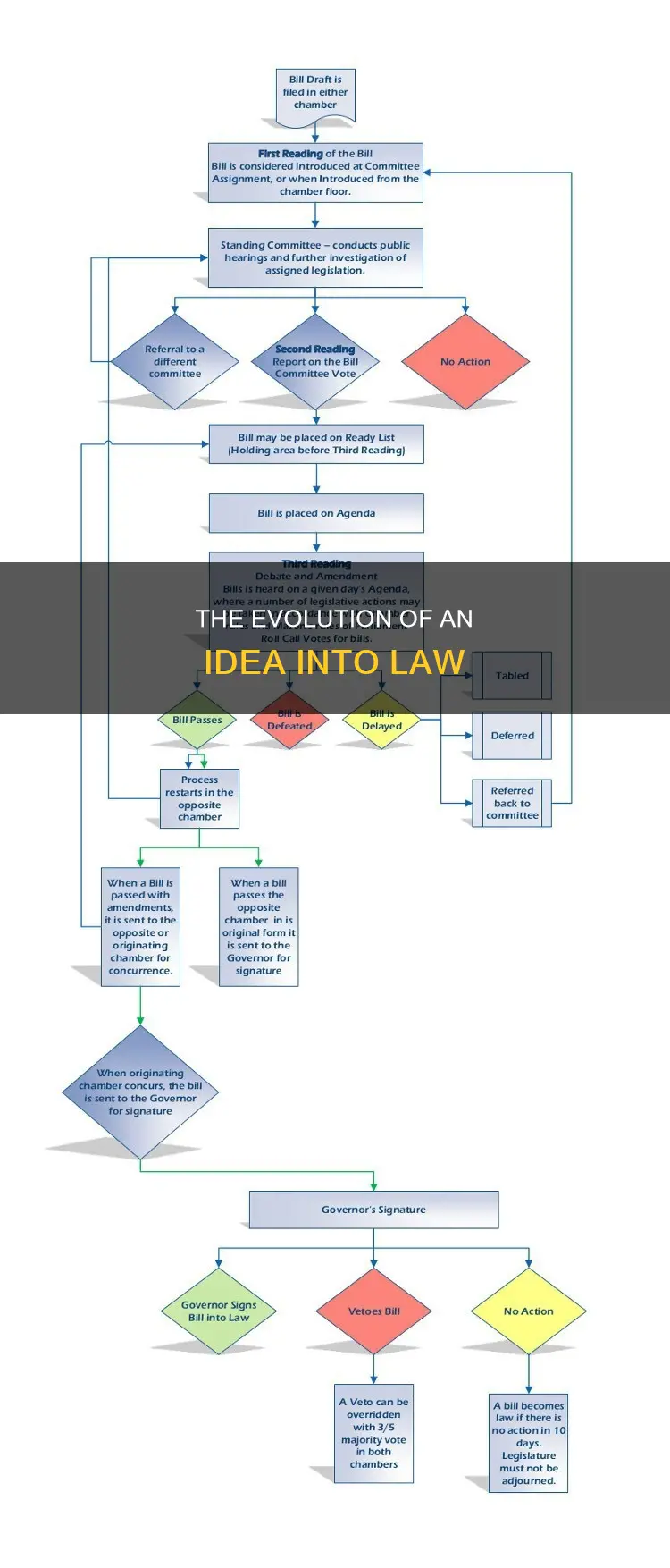

In Massachusetts, any citizen can request that their State Representative or State Senator file a bill, meaning that anyone can be the originator of a new law. The State Rep or Senator then files the bill in the House or Senate, where it is given a number – H for the House, and S for the Senate. The bill is then sent to a committee relevant to its topic, where a public hearing takes place. After the hearing, the committee decides whether to pass the bill on, reject it, or send it for Study (which usually kills the bill). If the bill passes this stage, it goes through three readings and can be debated and amended by State Reps and Senators.

What You'll Learn

The role of citizens and legislators in proposing an idea for a bill

In Massachusetts, citizens can ask their legislators to present bills "by request", which means that the bills do not necessarily have the support of the legislators who file them. This is the first step in the cycle of a bill becoming a law. The legislators can then file the bill in the House or Senate Clerk's office, where it is given an initial number and recorded in a docket book. The bill then goes through three readings in each branch, during which it is considered, debated, and amended. Citizens can attend the hearings and address the committee.

Legislators, including members of the House and Senate, can also file legislation. The Governor may also file legislation at any time. Once a legislator's bill is filed, it is given an initial number and recorded in a docket book. The bill is then assigned a bill number and sent to the appropriate Joint Committee, which holds a hearing and issues a report. The committee may recommend changes or redraft the bill entirely. If the bill receives a favorable recommendation, it moves through the legislative process, which includes the three readings in each branch.

Understanding Delegated Legislation: How It Becomes Law

You may want to see also

The process of introducing a bill

In Massachusetts, a bill is first filed with the House or Senate Clerk's office by a legislator. It is then assigned to a committee and given a bill number, which is used to track the bill.

Every bill must then have a public hearing held by the committee to which it is assigned. For example, a bill providing access to healthcare will likely have a hearing before the Health Care Financing Committee. All members of the public are invited to give testimony in favour of or against the bill.

After a bill is heard in committee, the chairperson decides whether to report it out of committee favourably or unfavourably, or into a study order. A study order means the committee wishes to continue reviewing the legislation and does not plan to report it out favourably. If a bill is reported out favourably, it may go to another committee, especially if it involves money.

If a bill is reported out unfavourably, it will go to the Floor of that branch for concurrence, and if there is no objection, it will die on the floor. All bills relating to money originate in the House and go to the House Committee on Ways and Means. Other bills can go to the Ways and Means Committee, but this is not a good sign for the bill, as they often never come out of that committee.

If a bill makes it out of Ways and Means or another committee and then to the Committee on Steering Policy and Scheduling, it goes to the Committee on Third Reading. If reported out of that committee, it goes to the Floor of one branch, and if passed favourably, to the floor of the other branch.

The Law-Making Process: From Proposal to Enactment

You may want to see also

The role of committees and subcommittees in reviewing a bill

Committees play a crucial role in the legislative process, receiving and reviewing many bill referrals over the course of a Congress. The committees are made up of a small group of MPs, typically between 16 and 50, who are chosen based on their expertise in the particular field or area covered by the bill. The committee chair has the chief agenda-setting authority and identifies the bills or issues the committee will act on through hearings and/or a markup.

The first formal committee action on a bill might be a hearing, which provides a forum for committee members and the public to learn about the strengths and weaknesses of a proposal from selected parties, such as relevant industries and groups representing interested citizens. Hearings also spotlight legislation to colleagues, the public, and the press. Invited witnesses provide oral remarks and written feedback on the bill, after which committee members ask questions of the witnesses.

While hearings are the formal public setting for feedback, committees also engage in additional assessment through informal briefings and other mechanisms. A markup is the key formal step a committee takes for a bill to advance. The committee chair chooses the proposal for markup, and committee members consider possible changes by offering and voting on amendments. A markup concludes when the committee agrees by majority vote to report the bill to the chamber. Committees rarely hold a markup unless the proposal is expected to receive majority support.

Most House and Senate committees also establish subcommittees, which are subpanels where members can further focus on specific elements of the policy area. The role subcommittees play in policymaking varies, but they cannot report legislation to the chamber; only full committees may do so.

The Journey of a Bill to Becoming a Law

You may want to see also

The process of voting on a bill

In Massachusetts, the process of voting on a bill involves several stages, starting with the introduction of the bill, followed by debates, committee review, voting, and, ultimately, enactment. Here is a detailed overview of the process:

The process typically begins with a legislator, who drafts and introduces the bill. This legislator becomes the sponsor of the bill and is responsible for guiding it through the legislative process. The bill is then assigned a number and referred to the appropriate committee for consideration.

Committee Review

The committee stage is crucial, as it allows for a thorough examination of the bill. The committee reviews the bill, holds hearings, invites experts and stakeholders to provide testimony, and may propose amendments. This stage ensures that the bill is scrutinised and improved before proceeding further.

Floor Debate and Voting

After the committee stage, the bill returns to the full legislative chamber for debate and voting. This stage involves robust discussions, where legislators can voice their support or opposition to the bill. Amendments proposed by the committee or individual legislators may also be considered and voted on.

Final Passage

If the bill receives a majority vote, it moves forward. In some cases, a supermajority vote may be required, depending on the nature of the bill and the rules of the legislative body. The bill then moves to the other chamber for a similar process of debate and voting.

Reconciliation

If the bill passes in both chambers but with amendments, a conference committee may be formed to reconcile the differences between the two versions. This committee includes members from both chambers, who work together to create a final version of the bill acceptable to both sides.

Enactment

Once the bill passes both chambers in identical form, it is typically sent to the executive for approval. In some cases, this may be the governor or the president, who can choose to sign the bill into law or veto it. If vetoed, the bill may return to the legislature, which can override the veto with a higher majority vote. Finally, the bill is enacted and becomes a law in Massachusetts.

The Legislative Journey: Proposal to Law

You may want to see also

The role of the president in signing a bill into law or vetoing it

In the United States, the president plays a crucial role in the legislative process, as they have the power to sign bills into law or veto them. Once a bill has passed both chambers of Congress, it is enrolled and presented to the president for review. The president then has ten days, excluding Sundays, to make a decision. If the president approves of the bill, they will sign it, and it will become a law.

On the other hand, if the president disagrees with the bill, they can choose to veto it. A veto means that the president refuses to approve the bill and sends it back to Congress with a note explaining their reasons. However, Congress can override a presidential veto if there is a two-thirds majority in favour of the bill in both chambers. In this case, the bill will become a law even without the president's signature.

It is important to note that if the president does not act on the bill within the ten-day period and Congress remains in session, the bill will become a law without the president's signature. This is not the case if Congress has adjourned under certain circumstances, which is known as a "pocket veto". A pocket veto cannot be overridden by Congress, and the bill will not become a law.

Understanding the Process: Bills to Laws

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Members of the House and Senate and the Governor can file legislation. The state constitution also allows citizens to ask their legislators to present bills “by request”.

The bill filing deadline for legislators is 5:00 p.m. on the third Friday in January of the first annual session of the General Court. The Governor may file legislation at any time.

Once a bill is filed in the House or Senate Clerk's office, it is given an initial number (a docket number) and is recorded in a docket book. The bill is then assigned a bill number and the appropriate Joint Committee to hear it. Bills that originate in the House begin with “H” and those that originate in the Senate begin with “S.”

After being filed and assigned to a Joint Committee, the bill must go through three readings in each branch, during which it is considered, debated, and amended. If the bill receives a favorable recommendation at each stage, it moves to a conference committee, where differences between the House and Senate versions are resolved. Once both branches agree on a version, the bill proceeds to an enactment vote. Following enactment, the bill is sent to the Governor, who can sign it, veto it, or let it become law without their signature.

The legislative process can take up to two years, as legislative sessions are two years in length and begin in the odd-numbered year and end in the even-numbered year. However, once a bill is enacted and sent to the Governor, it typically becomes law within 90 days, unless it contains an emergency preamble or includes a specific effective date.