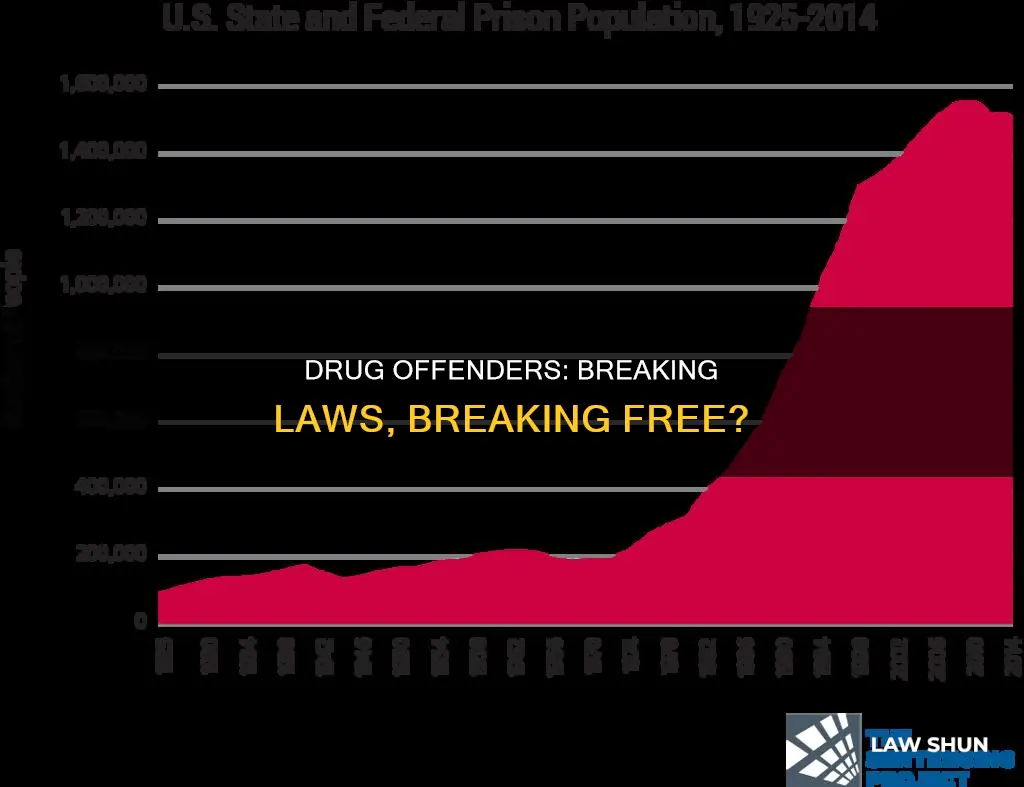

Drug-related offences are a significant factor in the high prison population in the United States. In 2011, there were an estimated 1.5 million arrests for drug offences, and by 2015, the number of federal prisoners serving time for drug offences had soared to 92,000, up from 5,000 in 1980. In 2023, 1 in 5 incarcerated people was locked up for a drug offence. While the exact rates of inmates with substance use disorders are hard to measure, some research suggests that 65% of the US prison population has an active substance use disorder, and a further 20% were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their crime.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of people in state and federal prisons for drug-law violations | Nearly 300,000 |

| Increase in the number of people in federal prisons for drug offences between 1980 and 2015 | 5,000 to 92,000 |

| Percentage of federal inmates who are drug offenders in 2015 | Nearly 50% |

| Number of people in local jails on drug charges in 2015 | 150,000 |

| Percentage of state prison and local jail inmates who have used an illegal drug | 80% |

| Percentage of state prison and local jail inmates who have used an illegal drug in the month before their arrest | 55% |

| Percentage of state prison inmates who were under the influence of drugs at the time of the offence | 32% |

| Percentage of state prison inmates who committed their crime to get money to buy drugs | 16.5% |

| Percentage of drug offenders rearrested within 3 years of release from prison | 68% |

What You'll Learn

- The US prison population has a strong connection to drug-related offences

- Treatment for substance use disorders is critical to reducing overall crime

- Inadequate treatment in prison contributes to overdoses and deaths after release

- Treatment for substance use disorders should begin in prison and continue after release

- Treatment for substance use disorders in the criminal justice system saves money in the long run

The US prison population has a strong connection to drug-related offences

The number of people in US prisons for drug-law violations has increased from less than 25,000 in 1980 to nearly 300,000 in 2018. The average time served has also increased, with the average time spent in state prisons increasing by 36% from 1990 to 2009, and federal drug offenders' prison terms jumping by 153% between 1988 and 2012.

The high rate of drug-related incarceration in the US is despite evidence that imprisonment does not reduce drug misuse. Research has found no statistically significant relationship between state drug imprisonment rates and indicators of state drug problems such as self-reported drug use, drug overdose deaths, and drug arrests. This suggests that policymakers should pursue alternative strategies to address drug misuse, as imprisonment has failed to act as a deterrent and has instead siphoned funds away from more effective programmes, practices, and policies.

The large number of individuals with substance use disorders involved in the US criminal justice system presents a unique opportunity to address public safety and public health concerns. However, a low proportion of those who could benefit from treatment actually receive it while involved in the criminal justice system. This is due to various factors, including knowledge gaps among criminal justice staff, scepticism towards treatment effectiveness, communication and collaboration problems, and resource constraints.

Effective treatment of substance use disorders for incarcerated individuals requires a comprehensive approach, including behavioural therapies, medications, and wrap-around services after release. Treatment must begin in prison and be sustained after release to be effective, but only a small percentage of those who need treatment while incarcerated actually receive it, and the treatment provided is often inadequate.

Obama's Campaign Finance: Legal or Unlawful?

You may want to see also

Treatment for substance use disorders is critical to reducing overall crime

Effective treatment of substance use disorders can reduce both drug use and crime after an inmate returns to the community. Treatment while incarcerated is critical to reducing recidivism and other societal burdens, such as lost productivity, family disintegration, and overdoses and deaths upon release.

There are several challenges in addressing substance use disorders in this population. Treatment must begin in prison and be sustained after release through community treatment programs. However, only a small percentage of those who need treatment while incarcerated actually receive it, and the treatment provided is often inadequate.

Inmates with opioid use disorders pose a particular challenge. Many untreated inmates will experience a reduced tolerance to opioids while in prison, and upon release, they may return to previous levels of use, unaware that their bodies can no longer tolerate the same doses, increasing their risk of overdose and death.

Several effective treatment models exist for linking offenders to treatment within correctional institutions and in the community, at all points in the criminal justice process. Diversion models, such as TASC, DTAP, and SACPA, have been shown to reduce drug use and recidivism. Legally mandated treatment can improve retention, and treatment outcomes can be similar for offenders in mandated and non-mandated treatment.

Brief psychosocial interventions, treatment referral monitoring, and the initiation of community-based medication-assisted treatment (MAT) can help link jail inmates to community treatment and improve post-release outcomes. MAT has been shown to be effective in reducing reoffending and relapse, but it is rarely used in the criminal justice system due to negative views, security concerns, and resource constraints.

Overall, the delivery of effective drug treatment in the criminal justice system can be challenging, and there is a substantial gap in treatment access. However, by increasing knowledge about how to integrate treatment at all stages of the criminal justice process, it is possible to expand access to effective drug treatment for offenders, with the potential to improve both public health and public safety.

Obama's Legacy: Lawbreaker or Law-Abiding?

You may want to see also

Inadequate treatment in prison contributes to overdoses and deaths after release

Inadequate treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs) in prison contributes to overdoses and deaths after inmates are released. In the US, an estimated 65% of the prison population has an active SUD, with a further 20% not meeting the official criteria for SUD, but having been under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their crime. Treatment for SUDs is critical to reducing drug use and crime after an inmate returns to the community. However, only a small percentage of those who need treatment while in prison actually receive it, and the treatment provided is often inadequate.

Inmates with opioid use disorders pose a particular challenge. During their time in prison, many untreated inmates will experience a reduced tolerance to opioids because they have stopped using drugs while incarcerated. Upon release, they may return to their previous levels of drug use, unaware that their bodies can no longer tolerate the same doses, increasing their risk of overdose and death. Insufficient pre-release counselling and post-release follow-up care are contributing factors to the high mortality rates among former prisoners.

Research has shown that providing comprehensive substance use treatment to criminal offenders while incarcerated is effective in reducing both drug use and crime. Treatment must begin in prison and be sustained after release through community treatment programs. By engaging in a continuing therapeutic process, individuals can learn to avoid relapse and withdraw from a life of crime. Effective treatment requires a comprehensive approach, including behavioural therapies, medications, and wrap-around services such as employment and housing assistance.

Despite the proven effectiveness of treatment, many prisons and jails in the US have been criticised for their inadequate response to the increase in overdoses. From 2001 to 2018, the number of people who died of drug or alcohol intoxication in state prisons rose by over 600%, and overdose deaths in county jails increased by more than 200%. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the issue, with restricted access to visitors, attorneys, and volunteers leading to increased drug use and overdoses among inmates.

The failure to provide adequate treatment for SUDs in the criminal justice system has negative societal implications and is costly. Inadequate treatment contributes to higher rates of recidivism, lost job productivity, family disintegration, and increased costs for communities. Alternatives to incarceration, such as drug courts, community supervision, and treatment programs, have been shown to be more effective in reducing drug use and crime, and have the support of a majority of US voters.

Psychopathy and Crime: A Complex Relationship Explored

You may want to see also

Treatment for substance use disorders should begin in prison and continue after release

Substance use disorders are prevalent in the prison population

The United States has a large prison population, with nearly 300,000 people held in state and federal prisons for drug-law violations. Substance use disorders (SUDs) are common among this population, with an estimated 65% of the US prison population having an active SUD, and a further 20% not meeting the official criteria for SUD but being under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their crime.

Treatment for substance use disorders is critical to reducing recidivism and improving health outcomes

Decades of scientific research has shown that providing comprehensive substance use treatment to offenders while incarcerated is effective in reducing both drug use and crime after release. Treatment while in prison is critical to reducing overall crime and other drug-related societal burdens, such as lost job productivity, family disintegration, and recidivism. Inadequate treatment while incarcerated also contributes to overdoses and deaths when inmates are released.

Treatment should begin in prison and continue after release

To be effective, treatment must begin in prison and be sustained after release through participation in community treatment programs. By engaging in a continuing therapeutic process, individuals can learn how to avoid relapse and withdraw from a life of crime. However, currently, only a small percentage of those who need treatment while in prison actually receive it, and the treatment provided is often inadequate.

Treatment options for substance use disorders in prisons

Treatment options for substance use disorders in prisons can include behavioural therapies such as cognitive-behavioural therapy and contingency management therapy, as well as medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Wrap-around services after release, including employment and housing assistance, are also important.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is particularly effective for opioid use disorder

MAT, which combines professional counselling or therapy with prescribed medications, is widely considered the gold standard of care for opioid use disorder. It has been shown to be more effective than other treatments in reducing opioid use, increasing treatment participation, reducing injection drug use, and decreasing transmission of HIV and hepatitis C. However, MAT is rarely used in the criminal justice system, with only 5% of people with opioid use disorder in jail and prison settings receiving medication treatment.

Treatment for substance use disorders in prisons can reduce recidivism and improve health outcomes

Research has shown that treatment for substance use disorders in prisons can reduce recidivism and improve health outcomes. For example, a study of the Drug Treatment Alternative-to-Prison program (DTAP) found that it decreased the rearrest odds by 42% and had a benefit-cost ratio of 2.17. Additionally, a review of prison therapeutic community (TC) programs found that they reduced recidivism and relapse when combined with aftercare treatment following release.

Barriers to providing effective treatment for substance use disorders in prisons

There are several barriers to providing effective treatment for substance use disorders in prisons, including knowledge gaps and negative attitudes among criminal justice staff, communication and collaboration problems between criminal justice and treatment agencies, and resource constraints. Additionally, the fragmented nature of the criminal justice process presents challenges in implementing integrated treatment and providing continuity of care.

In conclusion, treatment for substance use disorders should begin in prison and continue after release to effectively reduce substance use, overdose, recidivism, and reincarceration. By addressing substance use disorders, both public health and public safety can be improved.

Breaking China's Population Law: Strategies and Motivations

You may want to see also

Treatment for substance use disorders in the criminal justice system saves money in the long run

The high incarceration rates in the United States are strongly linked to drug-related offences. While the exact rates of inmates with substance use disorders (SUDs) are hard to measure, research shows that an estimated 65% of the US prison population has an active SUD, with a further 20% not meeting the official criteria for SUDs but being under the influence of drugs or alcohol when they committed their crimes.

Treatment Effectiveness

Decades of scientific research have shown that providing comprehensive substance use treatment to criminal offenders while incarcerated works, reducing both drug use and crime after an inmate returns to the community. Treatment while in jail or prison is critical to reducing overall crime and other drug-related societal burdens, such as lost job productivity, family disintegration, and a continual return to jail or prison, known as recidivism.

Treatment Challenges

To be effective, treatment must begin in prison and be sustained after release through community treatment programs. By engaging in a continuing therapeutic process, people can learn how to avoid relapse and withdraw from a life of crime. However, only a small percentage of those who need treatment while behind bars actually receive it, and often the treatment provided is inadequate.

Treatment for Opioid Use Disorders

Inmates with opioid use disorders pose a particular challenge. During their time in prison, many untreated inmates will experience a reduced tolerance to opioids because they have stopped using drugs. Upon release, many will return to previous levels of use, not realising their bodies can no longer tolerate the same doses, increasing their risk of overdose and death. One study found that 14.8% of all former prisoner deaths from 1999 to 2009 were related to opioids. Insufficient pre-release counselling and/or post-release follow-up are partially responsible for this increase in mortality.

Cost of Treatment

Failure to treat substance use disorder in the criminal justice system not only has negative societal implications but also proves to be expensive. One study of people involved in the criminal justice system in California showed that engagement in treatment was associated with lower costs of crime in their communities in the 6 months following treatment. The economic benefits were far greater for individuals receiving time-unlimited treatment.

A report from the National Drug Intelligence Center estimated that the cost to society for drug use was $193 billion in 2007, a substantial portion of which—$113 billion—was associated with drug-related crime, including criminal justice system costs and costs borne by victims of crime. The same report showed that the cost of treating drug use (including health costs, hospitalizations, and government specialty treatment) was estimated to be $14.6 billion, a fraction of these overall societal costs. It is estimated that the cost to society has increased significantly since the 2007 report, given the growing costs of prescription drug misuse.

Despite the cost, treatment in the criminal justice system saves money in the long run.

Omorosa's Actions: Federal Law Violation?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

1 in 5 incarcerated people is locked up for a drug offense.

While the exact rates of inmates with substance use disorders (SUDs) are difficult to measure, some research shows that an estimated 65% of the US prison population has an active SUD.

20% of drug offenders did not meet the official criteria for an SUD, but were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their crime.

68% of drug offenders are rearrested within 3 years of release from prison.

It is unclear what percentage of drug offenders have committed a violent crime, however, stimulants such as cocaine or methamphetamine have psychopharmacological effects that can increase the likelihood of engaging in violent crime.