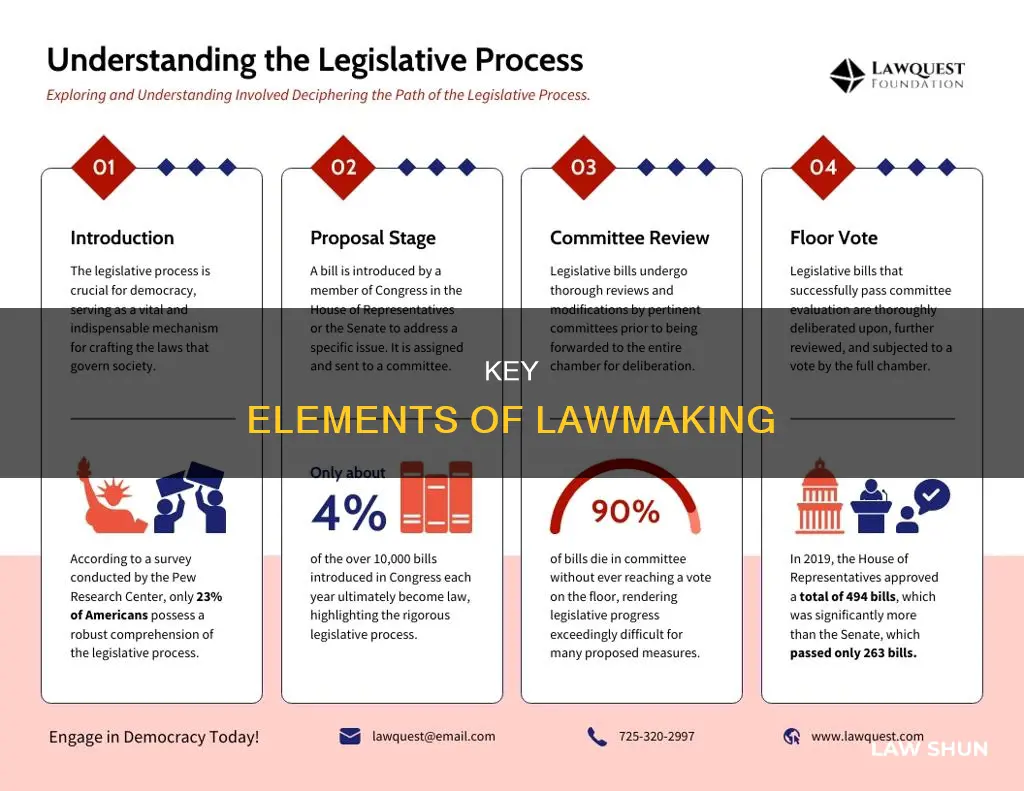

The process of lawmaking is a complex one, with many steps and requirements. In the US, Congress is the lawmaking branch of the federal government, and a bill is a proposal for a new law or a change to an existing one. The idea for a bill can come from a sitting member of Congress or be proposed during their election campaign. Bills can also be petitioned by citizens or groups who recommend a new or amended law to their representative.

Once introduced, a bill is assigned to a committee, which researches, discusses, and makes changes to it. The bill is then put before the chamber for a vote. If it passes one body of Congress, it goes through a similar process in the other body. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must work out any differences, and then both chambers vote on the same version. If it passes, they present it to the president for approval or veto.

The president's approval is the final step in passing a bill into law. However, if the president chooses to veto it, Congress can override that veto with a two-thirds majority vote in both chambers. This process, with its many steps and requirements, ensures that laws are carefully considered and reflect the interests of the people.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Creation | A law can be created by a legislature, resulting in statutes; by the executive through decrees and regulations; or by judges' decisions, which form precedent in common law jurisdictions. |

| Influence | The creation of laws may be influenced by a constitution, written or tacit, and the rights encoded therein. |

| Scope | The scope of law can be divided into public law and private law. Public law concerns government and society, while private law deals with legal disputes between parties. |

| Enforcement | Laws are enforced by social or governmental institutions. |

What You'll Learn

The creation of laws

Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee, whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to it. The bill is then put before that chamber for a vote. If it passes one body of Congress, it goes through a similar process in the other body. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must work out any differences between the two versions. Then, both chambers vote on the same version of the bill. If it passes, they present it to the president for approval.

The president can choose to approve the bill and sign it into law, or they can refuse to approve it, which is called a veto. If the president chooses to veto, Congress can vote to override that veto, and the bill becomes a law. However, if the president does not sign off on a bill and it remains unsigned when Congress is no longer in session, the bill will be vetoed by default, which is called a pocket veto.

Build Back Better: Law or No?

You may want to see also

The role of Congress

The United States Congress is made up of the House of Representatives and the Senate, which together form the legislative branch of the federal government. The Constitution grants Congress the sole authority to enact legislation and declare war, the right to confirm or reject many Presidential appointments, and substantial investigative powers.

Congress is the law-making branch of the federal government. A bill is a proposal for a new law or a change to an existing law. The idea for a bill can come from a sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, be proposed during their election campaign, or be petitioned by citizens or citizen groups. Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill. The bill is then put before that chamber to be voted on. If the bill passes one body of Congress, it goes to the other body to go through a similar process of research, discussion, changes, and voting. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must work out any differences between the two versions. Then both chambers vote on the same version of the bill. If it passes, they present it to the president.

The House of Representatives is made up of 435 elected members, divided among the 50 states in proportion to their total population. In addition, there are 6 non-voting members, representing the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and four other territories of the United States: American Samoa, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands. The presiding officer of the chamber is the Speaker of the House, elected by the Representatives. Members of the House are elected every two years and must be 25 years of age, a U.S. citizen for at least seven years, and a resident of the state (but not necessarily the district) they represent.

The House has several powers assigned exclusively to it, including the power to initiate revenue bills, impeach federal officials, and elect the President in the case of an Electoral College tie. The House also has the power to impeach the President, present impeachment charges, and conduct impeachment trials.

The Senate is composed of 100 Senators, 2 from each state. Senators are elected to six-year terms by the people of each state and their terms are staggered so that about one-third of the Senate is up for reelection every two years. Senators must be 30 years of age, U.S. citizens for at least nine years, and residents of the state they represent.

The Vice President of the United States serves as President of the Senate and may cast the decisive vote in the event of a tie in the Senate. The Senate has the sole power to confirm Presidential appointments and to provide advice and consent to ratify treaties. There are, however, two exceptions to this rule: the House must also approve appointments to the Vice Presidency and any treaty that involves foreign trade. The Senate also tries impeachment cases for federal officials referred to it by the House.

In order to pass legislation and send it to the President for his or her signature, both the House and the Senate must pass the same bill by majority vote. If the President vetoes a bill, Congress may override the veto with a two-thirds vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The Legislative Labyrinth: How a Bill Becomes Law

You may want to see also

The role of the President

The President of the United States has a significant role in the process of a bill becoming a law. As the head of state and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, the President is responsible for implementing and enforcing the laws written by Congress.

Once a bill has been introduced and assigned to a committee, researched, discussed, and changed, it is then put before the chamber to be voted on. If the bill passes one body of Congress, it goes through the same process in the other body. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must reconcile any differences between the two versions. Then, both chambers vote on the same version of the bill, and if it passes, it is presented to the President.

The President has the power to approve a bill and sign it into law, or to veto it. If the President chooses to veto a bill, Congress can override the veto with a two-thirds vote of both houses, and the bill will become a law. If the President does not sign off on a bill and Congress is no longer in session, the bill will be vetoed by default, known as a "pocket veto", which cannot be overridden by Congress.

The President also has the power to propose bills. A bill can be proposed by a sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, or be proposed during their election campaign. The President can also make suggestions about things that should be new laws.

Enrolled Bills: Laws in the Making

You may want to see also

The role of the Judiciary

The judiciary is a crucial component of the law-making process, comprising judges who mediate disputes and determine outcomes. While the specific structure and functions of the judiciary may vary across different countries and legal systems, its role in interpreting and applying the law remains fundamental. Here is an overview of the role of the judiciary in the law-making process:

Interpreting and Applying the Law

The judiciary plays a pivotal role in interpreting and applying the law. Judges are responsible for examining the language and intent of laws, ensuring they are understood and enforced consistently and fairly. They consider the context, purpose, and legislative history of laws to determine their meaning and how they should be applied in specific cases.

Dispute Resolution and Adjudication

A key function of the judiciary is to resolve disputes between parties. This involves hearing arguments, reviewing evidence, and applying relevant laws to reach a decision. Judges act as impartial decision-makers, ensuring that disputes are resolved in a fair and just manner, in accordance with the law.

Precedent and Case Law

The decisions made by judges in similar cases establish precedents that guide future rulings. This concept, known as case law or common law, means that past judicial decisions can influence how future cases are handled. Judges rely on precedents to ensure consistency and predictability in the application of the law.

Constitutional Interpretation

In many countries, the judiciary has the power to interpret and enforce the constitution. They ensure that laws and government actions align with constitutional principles, protecting the rights and freedoms of citizens. This role is crucial in maintaining the balance of power between different branches of government.

Law-Making Process and Checks and Balances

The judiciary works in conjunction with the legislative and executive branches to create and enforce laws. In some countries, the judiciary can review and strike down laws that are deemed unconstitutional, acting as a check on the power of the legislature. This dynamic helps maintain a system of checks and balances, preventing any one branch from having excessive power.

Promoting Fairness and Justice

The judiciary is responsible for ensuring that laws are applied fairly and justly. Judges are expected to be impartial and objective, treating all parties equally before the law. They safeguard the rights of individuals, ensuring that legal proceedings are conducted according to established rules and procedures.

Understanding Lawmaking: Junior Scholastic Worksheet Guide

You may want to see also

The enforcement of laws

The power to enforce the law is typically vested in the government, which includes the authority to investigate, arrest, and prosecute suspects. This power is often delegated to specific agencies and departments, such as the police, who are responsible for ensuring that laws are obeyed and upheld. The primary duties of law enforcement agencies include investigating crimes, apprehending suspects, and ensuring public safety. They work to gather evidence, identify perpetrators, and make arrests, playing a crucial role in maintaining law and order in society.

In addition to law enforcement agencies, other entities also play a role in enforcing the law. For example, prosecutors and district attorneys represent the interests of the state in criminal cases, presenting evidence and arguments to hold offenders accountable. On the other hand, defense attorneys represent individuals accused of crimes, ensuring that their rights are protected and that law enforcement and the prosecution act within the boundaries of the law. This dynamic helps maintain a balance between upholding the law and protecting the rights of the accused.

Furthermore, the role of the judiciary is crucial in enforcing the law. Courts interpret and apply the law, resolving disputes and determining the guilt or innocence of accused individuals. They also have the power to overturn laws or parts of laws that conflict with higher laws or the constitution, as seen in some countries where the highest judicial authority can overrule legislation deemed unconstitutional.

Overall, the enforcement of laws is a multifaceted process involving various entities, each playing a specific role to ensure compliance with established rules and regulations. Effective law enforcement is essential for maintaining social order, deterring crimes, and protecting the rights and freedoms of citizens.

Diane Explains: How a Bill Becomes a Law

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A law is a set of rules that are created and enforced by social or governmental institutions to regulate behaviour.

In the US, laws are made by Congress, which is the lawmaking branch of the federal government.

A bill is a proposal for a new law or a change to an existing law. Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee, which researches, discusses, and makes changes to it. The bill is then put before the chamber to be voted on. If the bill passes one body of Congress, it goes through a similar process in the other body. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must work out any differences between the two versions. Then both chambers vote on the same version of the bill. If it passes, they present it to the president. The president can either approve the bill and sign it into law, or refuse to approve it, which is called a veto. If the president chooses to veto a bill, Congress can vote to override that veto and the bill becomes a law.

There are four main types of law: constitutional, statutory, administrative, and common law.

Some examples of specific laws include criminal law, contract law, property law, and tax law.