The process of a bill becoming a law is long and complex, and only a small percentage of bills make it through to become law. In the US, bills must pass both houses of Congress and be signed into law by the President. Since World War II, Congress has typically enacted 4-6 million words of new law every two years, but this has been in fewer but larger bills, so the number of bills enacted into law is generally decreasing. Less than 10% of proposed bills become laws, with some sources giving a figure of 6%.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Percentage of bills that become law | Less than 5-10% |

| Number of words of new law enacted by Congress in each two-year session | 4-6 million |

| Number of bills enacted into law | Decreasing |

What You'll Learn

Less than 10% of bills become laws

The process of a bill becoming a law is long and difficult. Less than 10% of proposed bills become laws. The United States government makes potential laws available so that citizens can keep informed about what their government is doing and communicate their opinions to their legislators.

The legislative process begins with a new policy idea. Ideas for laws can come from ordinary citizens, the president, offices of the executive branch, state legislatures and governors, congressional staff, and members of Congress themselves. Once an idea for a new law has been settled on, it must be drafted as a bill before it can be considered by the Senate. Bill drafting requires specialized legal training and is usually carried out by the staff of New York State's Legislative Bill Drafting Commission.

After being drafted, a bill is introduced in one of the houses of Congress and assigned a number. Bills in the Senate are abbreviated as in S. 213, while bills in the House of Representatives are abbreviated as in H.R. 1171. The bill number will remain the same even if the bill itself is amended multiple times.

A bill must then work its way through both houses of Congress before it is sent to the president for their signature. In the House, a bill goes from committee to a special Rules Committee that sets time limits on debate and rules for adding amendments. In the Senate, rules for debate are much looser, and senators are allowed to talk for as long as they like about each bill.

If a bill passes both houses of Congress, it is signed into law by the president. However, if a bill does not complete the legislative process during the same congressional session in which it was proposed, it is dropped and must be reintroduced in the next session.

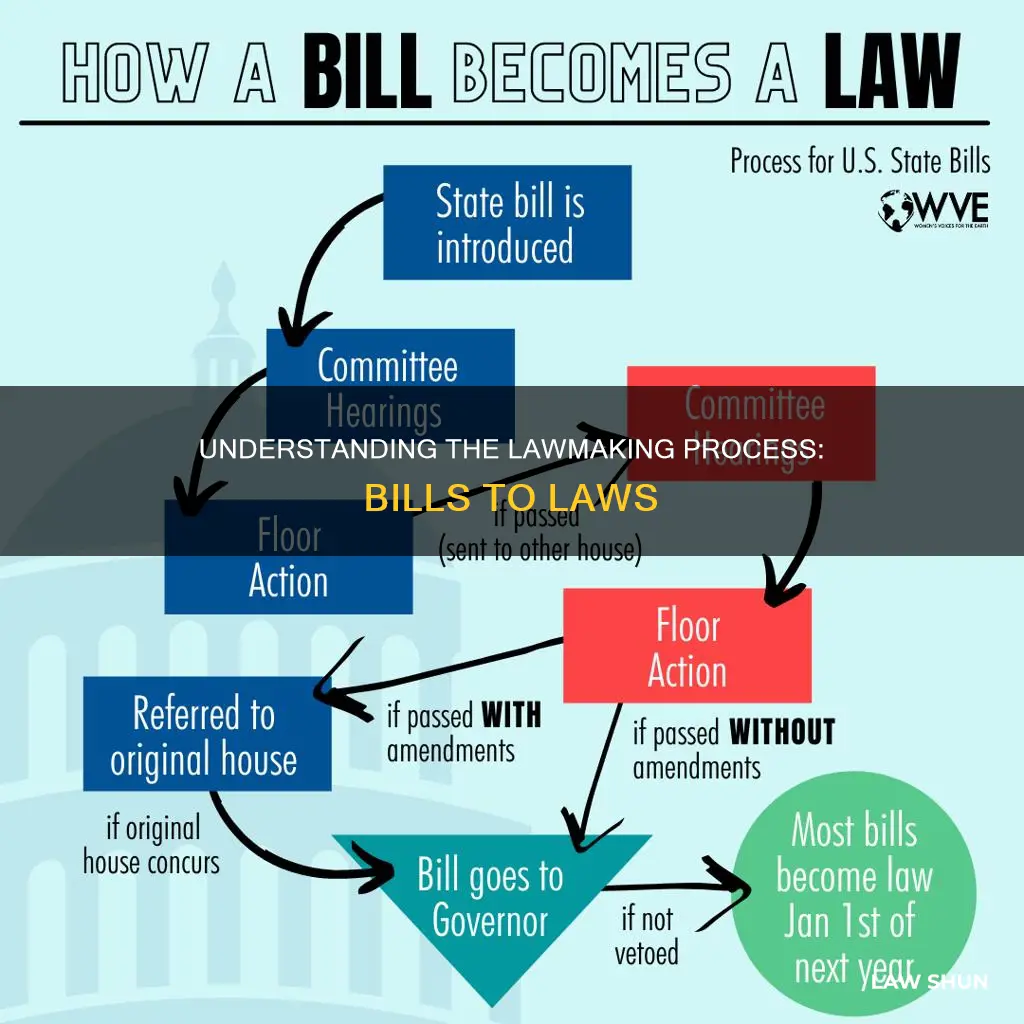

Understanding Lawmaking: A Bill's Journey to Becoming Law

You may want to see also

Bills must pass both houses of Congress

For a bill to become a law, it must pass both houses of Congress and be signed by the President. The process is long and arduous, and less than 10% of proposed bills become laws. The bill must be passed during the same congressional session in which it was proposed, which lasts for one year. If it does not complete the process, it is dropped and must be reintroduced to be considered again.

The first step in the process is the introduction of the bill to a committee. Bills are generally introduced by legislators or standing committees of the Senate and Assembly. The bill is then sent to the appropriate standing committee, which evaluates it and decides whether to send it to the Senate floor for a final decision. The committee may also amend or reject the bill. This is where most bills—about 90%—are "pigeonholed" or simply forgotten and never discussed.

If a bill survives the committee stage, hearings are set up, and various experts, government officials, or lobbyists present their points of view to the committee members. After the hearings, the bill is revised until the committee is ready to send it to the floor. In the House, a bill goes from the committee to a special Rules Committee that sets time limits on debate and rules for adding amendments. Rules for debate on the Senate floor are much looser, and there are no restrictions on amendments.

The final stage is the vote. A bill generally requires a majority vote by the members present to pass. If the bill passes, it is sent to the other house of Congress for consideration. If it is approved without amendment, it goes on to the President. However, if it is changed, it is returned to the first house for approval of the amendments.

The Legislative Hurdle: Bills to Laws

You may want to see also

Bills must be signed by the President

Once a bill has passed both houses of Congress, it is sent to the President for their signature. This is the final stage of the legislative process, and only about 6% of bills introduced in Congress make it this far. If a bill is not passed by the end of the congressional term, it is dropped and must be reintroduced in the next session if it is to be pursued.

The President has 10 days (not counting Sundays) to sign or veto bills passed by both houses. Signed bills become law, while vetoed bills do not. If the President fails to sign or veto a bill within the 10-day period, it becomes law automatically. Vetoed bills can still become law if two-thirds of the members of each house of Congress vote to override the veto.

If Congress is not in session when a bill is sent to the President, the rules are slightly different. In this case, the President has 30 days to make a decision, and failure to act within this period has the same effect as a veto.

The President's signature is not usually required on resolutions. However, joint resolutions (JRs) can be introduced for Constitutional Amendments, new legislation, or continuing appropriations, and these require the President's signature (except for Constitutional amendments) to have the force of law.

Injustice Laws: Resistance, Resilience, and Revolution

You may want to see also

Bills can be vetoed by the President

The process of a bill becoming a law is a complex and lengthy one. In the United States, a bill must pass through both houses of Congress and be signed into law by the President. This process includes several stages, such as committee consideration, floor debate, and conference committees. However, one of the most significant aspects is the potential for a bill to be vetoed by the President.

The President's power to veto a bill is a crucial aspect of the legislative process. Once a bill has passed through both houses of Congress, it is presented to the President for their signature. At this stage, the President has the authority to veto the bill, effectively blocking it from becoming a law. This power of veto provides a significant check and balance on the legislative process, allowing the President to exert their influence and ensure that only carefully considered and deliberate bills become laws.

The process of a bill becoming a law can be challenging, and the President's veto power adds another layer of complexity. When a bill is vetoed, it is returned to the house that first passed it, along with a statement outlining the reasons for the veto. This statement is essential, as it provides transparency and insight into the President's objections. It also allows for the possibility of further negotiation and compromise to address the President's concerns.

However, it is important to note that a vetoed bill is not necessarily dead. There is a mechanism in place to override a presidential veto. If two-thirds of the members of each house of Congress vote to override the veto, the bill can still become a law. This process underscores the importance of consensus-building and negotiation in the legislative process, as it requires a significant majority to overturn the President's decision.

The power of the President to veto a bill is a significant aspect of the legislative process in the United States. It provides a check on the power of Congress and ensures that only carefully considered bills become laws. While it adds complexity to the process, it also reinforces the democratic nature of the system, requiring negotiation and consensus-building to address any objections raised by the President.

Understanding the Lawmaking Process: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

Bills can die in committee

The legislative process is long and arduous, and there are many opportunities for a bill to be killed before it becomes law. In fact, most bills never become law, with less than 6% of legislation introduced in Congress making it through the legislative process. One source puts the figure even lower, at less than 5%.

The first stage a bill must survive is committee consideration. New bills are sent to standing committees by subject matter. For example, bills on farm subsidies generally go to the Agriculture Committee, while bills proposing tax changes would go to the House Ways and Means Committee. Given the large volume of bills, most are sent directly to a subcommittee.

Committees and subcommittees act as a funnel and a sieve for the large number of bills introduced each session. They are the first stage at which a bill can be killed, and most bills do die in committee or subcommittee, where they are pigeonholed or simply forgotten and never discussed.

If a bill survives committee consideration, hearings are set up in which various experts, government officials, or lobbyists present their points of view to committee members. After the hearings, the bill is marked up or revised until the committee is ready to send it to the floor.

The Journey of a Bill to Law Visualized

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Less than 10% of proposed bills become law. Since World War II, Congress has enacted 4-6 million words of new law in each two-year congressional session. However, these words are enacted in fewer but larger bills.

A bill must pass both houses of Congress and be signed into law by the President. It may begin its journey at any time but must be passed during the same congressional session of its proposal, which is a period of one year. If it does not complete the process, it is dropped and can only be revived through reintroduction.

If a bill is not passed by the end of the congressional term, it is not carried over to the next congress. Instead, it "dies" at the end of the term.