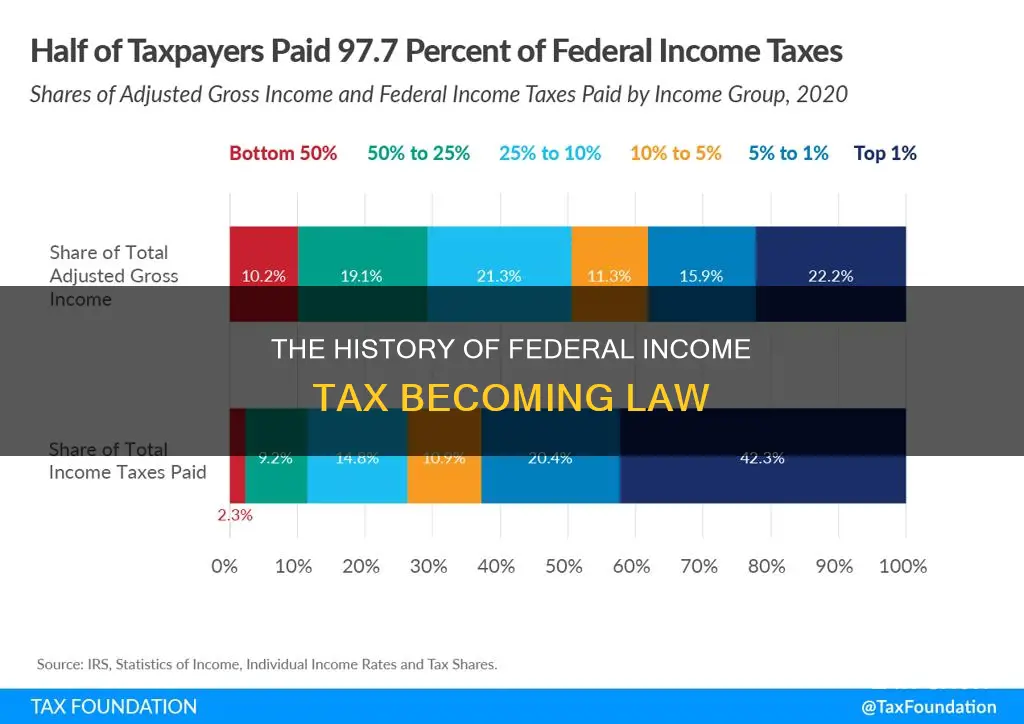

The 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on February 3, 1913, established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax. Before this, federal government revenues came mainly from taxes on goods, with tariffs on imported products and excise taxes on items like whiskey. The burden of these taxes fell heavily on working Americans, who spent a much higher percentage of their income on goods than rich people. The new amendment shifted the tax burden to the wealthy, with a 2% income tax on those earning $4,000 or more a year (less than 1% of the population at the time).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date federal income tax became law | 1913 |

| Amendment number | 16th Amendment |

| Date of ratification | 3rd February 1913 |

| Date passed by Congress | 2nd July 1909 |

| Number of states required for ratification | 36 |

| Number of states that ratified the amendment | 42 |

| Number of states that rejected the amendment | 6 |

| Date the amendment took effect | 25th February 1913 |

| Date of the first tax collection day under the new law | 1st March 1914 |

What You'll Learn

The Revenue Act of 1861

The Act was drafted by Congress under the leadership of Senator William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, in a relatively short time frame. It included import tariffs, property taxes, and an income tax. The bill provoked considerable debate in Congress, with Thaddeus Stevens, chairman of the House Committee of Ways and Means, calling it an "unpleasant" but necessary bill to sustain the government.

The income tax provision of the Act applied to only 3% of the population in the North, as it did not apply to the Southern states. It also lacked a comprehensive enforcement mechanism, which contributed to its failure to yield the desired revenue. As a result, the income tax provision was repealed in 1862 and replaced with a more expansive bill in the Revenue Act of 1862, which established the Internal Revenue Service and introduced a progressive tax scale.

The Evolution of Unconstitutional Laws: A Legal Journey

You may want to see also

The Civil War tax

The Civil War, which began in 1861, placed a significant financial burden on the federal government. The Union Army faced extraordinary expenditures as it trained and armed a large volunteer force. To address this, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Revenue Act of 1861, which included the first federal income tax statute in the United States.

The Act imposed a flat tax of 3% on incomes above $800 (equivalent to $27,129 in 2023), with the goal of raising revenue to fund the Civil War. This tax was applicable to all individuals residing in the United States, regardless of the source of their income. While the Act was successful in introducing income tax, it lacked an effective enforcement mechanism, and the 3% flat tax rate did not generate the desired level of revenue.

In 1862, President Lincoln signed a bill amending the Revenue Act of 1861. This new law imposed a progressive tax scale, with a 3% tax on incomes between $600 and $10,000, and a 5% tax on higher incomes. The law was further modified in 1864, with a 5% tax on incomes between $600 and $5,000, a 7.5% tax on incomes between $5,000 and $10,000, and a 10% tax on all higher incomes.

The Confederacy also implemented an income tax during the Civil War, with its first national income tax measure authorized in 1863. This tax had a graduated structure, exempting wages up to $1,000, levying a 1% tax on the next $1,500, and a 2% tax on all additional income.

The federal income tax implemented during the Civil War was short-lived, as it was repealed in 1872. However, it set a precedent and demonstrated the potential of income tax as a source of government funding. The concept of income tax remained in political discussions, and it re-emerged in the late 19th century during the Progressive Era, when social and political reform movements advocated for a more equitable tax system. This led to the enactment of the 16th Amendment in 1913, which established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax.

Becoming a Law Office Assistant: Skills and Steps

You may want to see also

The Revenue Act of 1913

Federal income tax became law with the enactment of the Revenue Act of 1913. This act was made possible by the ratification of the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution earlier that year, which established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax. The 16th Amendment was passed by Congress on July 2, 1909, and ratified on February 3, 1913.

The Act was a key plank in Woodrow Wilson's 1912 presidential campaign, and with the Democrats in control of Congress, they moved quickly to enact their tariff and tax plans. The House passed its bill in May 1913 by a vote of 281-139, and the Senate passed its version of the bill on September 9, 1913, by a vote of 44-37. The differences between the two versions were reconciled, and the final changes were adopted by the Senate and House on October 2 and October 3, respectively. Wilson signed the bill into law on October 3, 1913.

The income tax provision affected about 2% of the population, levying a 1% tax on incomes above $3,000 for single filers and $4,000 for joint filers. The rate increased progressively for incomes above $20,000, with a 6% rate on incomes above $500,000. The Act also included a 2% tax on corporate incomes above $5,000, with a maximum rate of 15% for corporations with incomes above $500,000.

In addition to the income tax provisions, the Revenue Act of 1913 also had a significant impact on tariffs. Many goods, including raw wool, cattle, sheep, wheat, eggs, meat products, iron ore, pig iron, coal, and lumber, were made exempt from tariffs. Tariff rates for other goods were also significantly cut, such as yarn rates, which were reduced from 79.56% to 18%, and women's and children's dress goods, which were reduced from 99.7% to 35%.

History of 501(c)(3) Law: A Nonprofit's Tax Exemption

You may want to see also

The Pollock ruling

- The Constitution authorised the federal government to impose direct taxes if they were apportioned among the states by their population.

- The Income Tax Act of 1894 was unconstitutional because the income tax was a direct tax and therefore must be apportioned by state population.

- The distinction between direct and indirect taxes was well understood by the framers of the Constitution and those who adopted it.

- Under the state systems of taxation, all taxes on real estate or personal property or the rents or income thereof were regarded as direct taxes.

- The rules of apportionment and of uniformity were adopted in view of that distinction and those systems.

- The original expectation was that the power of direct taxation would be exercised only in extraordinary exigencies, and down to August 1894, this expectation had been realised.

The Journey of a Bill to Law Exhibit

You may want to see also

The Brushaber ruling

The Supreme Court ruled that the 16th Amendment was constitutionally valid and did not alter or repeal any part of the Constitution. The Court clarified that the Amendment did not confer a new power to levy income taxes but relieved income taxes from the requirement of apportionment based on population. The Court further concluded that income taxes are indirect taxes, specifically excise taxes, and not direct taxes. This distinction was critical because, under the U.S. Constitution, indirect taxes must be uniform across states, while direct taxes must be apportioned based on population.

However, the Brushaber ruling has also been subject to criticism and debate. Some legal scholars, such as Jeffrey Dickstein and Vern Holland, argue that the ruling contradicts earlier Supreme Court decisions like Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. and subsequent rulings like Eisner v. Macomber. They contend that the Brushaber Court failed to provide a convincing legal basis for its conclusion that income taxes are indirect excise taxes. These critics maintain that income taxes are direct taxes that should be subject to apportionment, even after the 16th Amendment.

Becoming a Man of Law: A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Federal income tax became law in 1913, after the ratification of the 16th Amendment.

The 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on February 3, 1913, established Congress's right to impose a federal income tax without apportioning it among the states on the basis of population.

The 16th Amendment shifted the tax burden from the working classes to the wealthy, as taxes could now be levied on incomes, "from whatever source derived".