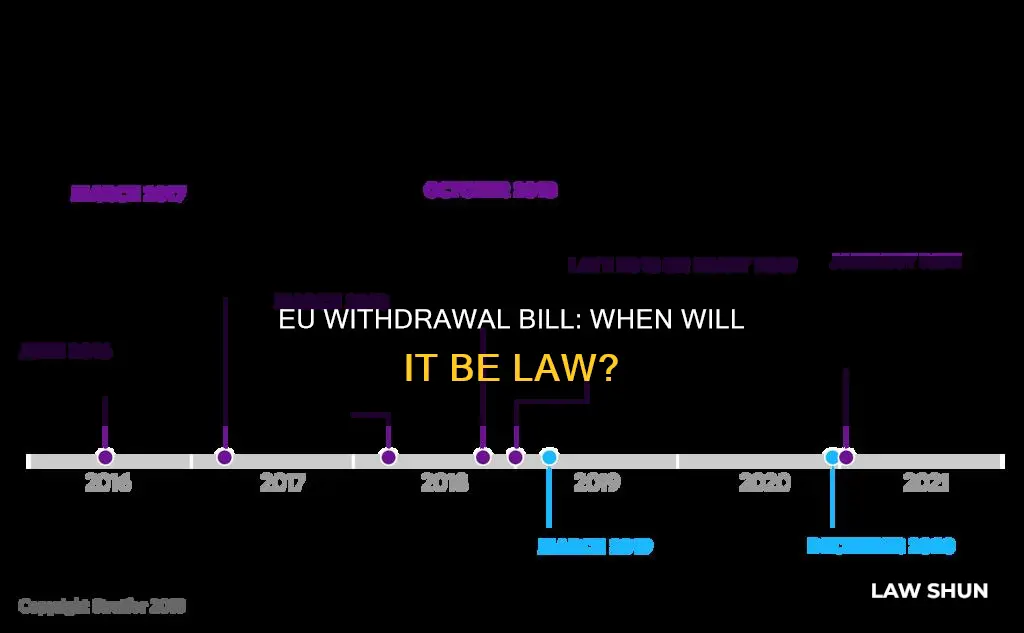

The UK's withdrawal from the EU became law on 31 January 2020 at 23:00 GMT, ending 47 years of membership. The process began when the UK Government triggered Article 50 on 29 March 2017, following a referendum held in June 2016, and the withdrawal was initially scheduled for 29 March 2019. The UK then sought and was granted a number of Article 50 extensions until 31 January 2020. The UK-EU withdrawal agreement was ratified by the UK Parliament on 23 January 2020 and by the European Parliament on 29 January 2020. The agreement set out the terms of the UK's withdrawal from the EU and Euratom, covering areas such as money, citizens' rights, border arrangements, and dispute resolution. It also included a transition period to ensure frictionless trade until a long-term relationship was agreed upon.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of Royal Assent | 26 June 2018 |

| Date of Withdrawal Agreement | 24 January 2020 |

| Date of Withdrawal Agreement Ratification by the UK Parliament | 23 January 2020 |

| Date of Withdrawal Agreement Ratification by the European Parliament | 29 January 2020 |

| Date of Withdrawal Agreement Ratification by the Council of the European Union | 30 January 2020 |

| Date of Withdrawal | 31 January 2020 |

What You'll Learn

Repealing the European Communities Act 1972

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, initially proposed as the Great Repeal Bill, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom to repeal the European Communities Act 1972. The Act came into force on 31 January 2020 at 23:00 GMT, though it was amended by the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020, which saved the effect of the European Communities Act 1972 during the implementation period.

The European Communities Act 1972 was the piece of legislation that brought the UK into the European Union. It gave EU law supremacy over UK national law. The Act incorporated Community Law (later European Union Law), along with its acquis communautaire, its treaties, regulations, directives, decisions, the Community Customs Union (later European Union Customs Union), the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the Common Fisheries Policy (FCP) together with judgments of the European Court of Justice into the domestic law of the United Kingdom.

The Act legislated for the United Kingdom's accession to the European Economic Community (EEC), the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom). It also incorporated the following treaties into the domestic law of the United Kingdom:

- Treaty of Paris (1951)

- Budgetary Treaty of 1970

- Treaty of Accession 1972

The Act was repealed on 31 January 2020 by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, though its effect was 'saved' under the provisions of the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020. This provision was in effect from 31 January 2020 (when the United Kingdom formally left the European Union) until the end of the Brexit implementation period on 31 December 2020, when the "saving" provisions were automatically repealed.

The Evolution of Monogamy: From Custom to Law

You may want to see also

Ratifying the Withdrawal Agreement

The UK Government and the European Union reached an agreement on a revised Withdrawal Agreement (a draft treaty text) and Framework for the Future Relationship (a joint political declaration) on Thursday, 17 October 2019. However, this was not the end of the approval process. Each party must proceed to complete their respective constitutional requirements for ratifying the treaty before the Article 50 process can be brought to an end.

In general, treaties do not require proactive Parliamentary approval. Treaties are negotiated, signed, and ratified by the UK Government. However, Parliament has a role in the process that varies depending on the context and the type of treaty.

Some treaties need domestic law to be changed to ensure the UK can meet its (new) international obligations. When the UK Government negotiated an accession treaty to the European Economic Community, Parliament passed the European Communities Act 1972. Without that Act, UK courts would not have given effect to Community law, and the UK would have been in breach of its new commitments. If the UK cannot yet implement a treaty, it may be premature to ratify it.

In general, but not for all treaties, Part 2 of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (CRAG) requires the Government to lay a copy of the final treaty text before Parliament. Except in "exceptional cases" (where a Minister can disapply the waiting period), the Government must then wait 21 sitting days to allow Parliament to scrutinise the treaty. If time is made for a debate in the Commons, and MPs resolve against ratification of a treaty, this prevents the Government from ratifying it. However, since 2010 no treaty has been rejected in this way: legally, the Government does not need to make time for a debate to take place.

In the case of treaties concerned with the powers of the EU, domestic law has required an Act of Parliament to be passed before the Government can ratify. For example, the (now repealed) section 12 of the European Parliamentary Elections Act 2002 made it necessary to pass the European Union (Amendment) Act 2008 before the UK could ratify the Lisbon Treaty. Although it never had to be used, the European Union Act 2011 additionally imposed a referendum requirement on certain types of EU treaty change before the Government could proceed to ratify.

In July 2018, Parliament passed the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 ('the 2018 Act'). Section 13 of that Act states that a Withdrawal Agreement treaty cannot be ratified unless four conditions have been met:

- Copies of both the negotiated Withdrawal Agreement and the Framework for the Future Relationship have been laid before both Houses, with a "statement that political agreement has been reached".

- The House of Commons has, on a motion of a Minister, approved those documents (the so-called 'Meaningful Vote').

- The House of Lords has had the opportunity, on a motion of a Minister, to "take note of" those documents.

- A further Act of Parliament to implement the Withdrawal Agreement has been passed.

On Saturday 19 October 2019, only two of these conditions were met (the laying of documents and the holding of a debate in the House of Lords). MPs withheld approval for the revised Brexit deal, indicating that approval would only be forthcoming if and when the implementing legislation had passed.

Because the UK’s negotiated Withdrawal Agreement is not an exempted treaty under Part 2 of CRAG, the Government must also meet or supersede the conditions set down by that Act.

So why is the Government trying to ratify?

Notwithstanding the vote on Saturday, media reports suggest the Government has concluded it can now persuade a majority of MPs to support its efforts to ratify the Withdrawal Agreement. The fact that one of the approval conditions is the passage of a subsequent Act of Parliament means that, if MPs want to pass the Act, they can effectively override the existing ratification requirements. A core tenet of Parliamentary sovereignty is that a new Act of Parliament can override a prior one. The section below describes how the Government proposes to do this.

There are two key clauses in the WAB relevant to ratification: clause 32 and clause 33.

Clause 32 repeals section 13 of the 2018 Act. It makes clear that "none of the conditions" set out in that provision apply to the ratification of the Withdrawal Agreement. Passing the WAB with this clause included might function as a "proxy" for a Meaningful Vote: if MPs want to allow the Government to ratify the agreement, repealing section 13 achieves the same result.

Clause 33 stipulates that Part 2 of CRAG does not apply to the ratification of the Withdrawal Agreement. The Government therefore does not have to lay a copy of the final treaty or wait 21 sitting days for the purposes of that Act. However, it does not prevent the CRAG process from applying to any future treaty to modify the Withdrawal Agreement.

The UK Government will be able to ratify the Withdrawal Agreement once the EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill has received Royal Assent. The EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill completed its Parliamentary stages on 22 January 2020 and was expected to receive Royal Assent on 23 January 2020.

Amendments to Laws: The Process Explained

You may want to see also

Transition period

The transition period, also referred to as the implementation period, is a core part of the Withdrawal Agreement between the UK and the EU. It began when the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020 and ended on 31 December 2020. However, the Withdrawal Agreement does allow for the possibility of the transition period being extended.

During the transition period, the UK had to follow most EU laws in the same way as it did as an EU member state. However, the UK no longer had representation or voting rights in EU institutions. There were some exceptions to the continuation of EU law, which were set out in the Withdrawal Agreement.

The transition period was designed to ensure frictionless trade until a long-term relationship was agreed. If no agreement was reached by the end of the transition period, the UK would have left the single market without a trade deal on 1 January 2021.

The President's Role in Passing a Bill

You may want to see also

Citizens' rights

The EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, which became law in June 2018, legislates for the Withdrawal Agreement, EEA EFTA Separation Agreement, and Swiss Citizens' Rights Agreement. The bill protects the rights of EU citizens and EEA and Swiss nationals living and working in the UK.

The Withdrawal Agreement, which came into force on 1 February 2020, covers citizens' rights, both of British citizens in EU countries and vice versa. It defines and provides the personal scope of citizens, family members, frontier workers, host states, and nationals. Article 11 deals with the continuity of residence, and Article 12 discusses non-discrimination (i.e., it would be prohibited to discriminate on grounds of nationality).

The Agreement further states that British nationals and European Union citizens, as well as their family members, shall maintain the right to reside in the host state. The host state may not limit or condition the persons for obtaining, retaining, or losing residence rights. Persons with valid documentation would not require entry and exit visas or equivalent formalities and would be permitted to leave or enter the host state without complications. In the case that the host state demands "family members who join the Union citizen or United Kingdom national after the end of the transition period to have an entry visa", the host state is required to grant the necessary visas through an accelerated process in appropriate facilities free of charge.

The Agreement also deals with the issuance of permanent residence permits during and after the transition period, as well as its restrictions. It clarifies the rights of workers and self-employed individuals and provides recognition and identification of professional qualifications.

The EU-UK Joint Committee, co-chaired by the EU and the UK, is in charge of overseeing the implementation, application, and interpretation of the Withdrawal Agreement. The committee also supervises the six Specialised Committees, one of which is the Specialised Committee on Citizens' Rights, which was established to monitor the implementation and application of citizens' rights under the agreement.

The Evolution of NAFTA: A Historical Legislative Journey

You may want to see also

Northern Ireland Protocol

The Northern Ireland Protocol is part of the UK's Withdrawal Agreement with the EU. It sets out special arrangements for Northern Ireland, so that the island of Ireland remains border-free. The Protocol ensures that a hard border is avoided on the island of Ireland following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

The Protocol came into force on 1 January 2021. It is intended to protect the EU single market, while avoiding the imposition of a 'hard border' that might incite a recurrence of conflict and destabilise the relative peace that has held since the end of the Troubles.

Under the Protocol, Northern Ireland but not the rest of the UK remains in the EU single market for goods, allowing the maintenance of an open border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. In place of a Republic of Ireland/Northern Ireland land border, the protocol has created a de facto customs border in the Irish Sea, separating Northern Ireland from Great Britain.

The Protocol's terms were negotiated shortly before the 2019 general election and concluded immediately after it, in December of that year. The withdrawal agreement as a whole, including the protocol, was ratified in January 2020.

In February 2023, the European Commission and the Government of the United Kingdom announced agreement in principle (the "Windsor Framework") to modifications of aspects of the operation of the protocol. The Windsor Framework was designed to address the problem of the movement of goods between the European Single Market and the United Kingdom. It introduced green and red lanes to reduce checks and paperwork on goods that are destined for Northern Ireland only, and separate them from goods at risk of moving into the EU Common Market.

The Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, introduced on 13 June, empowers ministers to disapply the Protocol and relevant parts of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement in domestic law, as well as to make new domestic law in place of what is set out in the Protocol.

Lynching: A Federal Crime, But When?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The EU Withdrawal Bill became law on 26 June 2018 after receiving Royal Assent.

The EU Withdrawal Bill, also known as the Great Repeal Bill, is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that repealed the European Communities Act 1972 and required parliamentary approval for the withdrawal agreement between the UK and the EU.

The EU Withdrawal Agreement is a treaty between the European Union (EU), Euratom, and the United Kingdom (UK) that sets the terms of the UK's withdrawal from the EU and Euratom. The agreement covers money, citizens' rights, border arrangements, dispute resolution, and the future relationship between the UK and the EU.