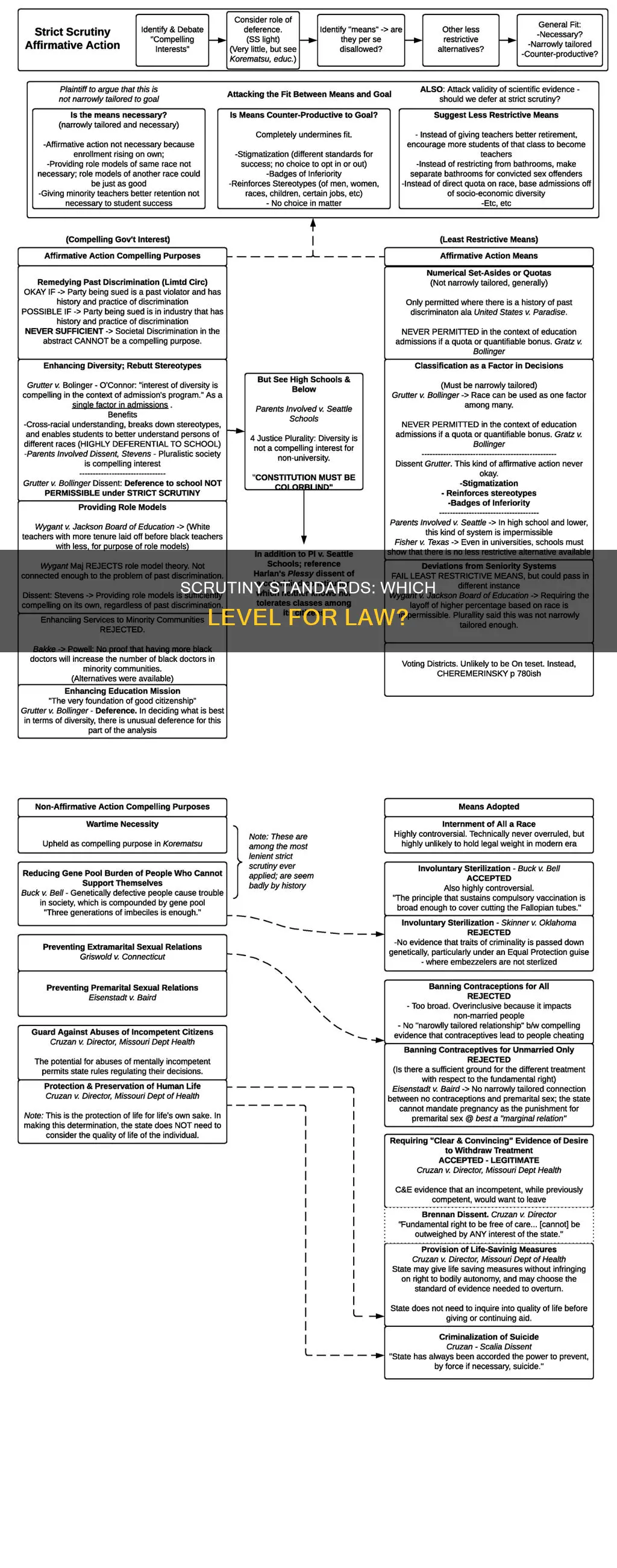

When the constitutionality of a law is challenged, both state and federal courts will apply one of three levels of judicial scrutiny: strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, and rational basis review. The level of scrutiny that is applied determines how a court will go about analysing a law and its effects, as well as which party has the burden of proof. Strict scrutiny is the highest level of scrutiny applied by courts to government actions or laws. It is used when a law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right or involves a suspect classification, such as race, religion, national origin, and alienage. Intermediate scrutiny is the next level of judicial focus on challenged laws and is used when a state or the federal government passes a statute that discriminates against or negatively affects certain protected classes. The lowest level of scrutiny is the rational basis review, which has historically required very little for a law to pass as constitutional.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Highest level of scrutiny | Strict scrutiny |

| Middle level of scrutiny | Intermediate scrutiny |

| Lowest level of scrutiny | Rational basis review |

| Strict scrutiny applied when | A law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right or involves a suspect classification |

| Suspect classification includes | Race, religion, national origin, and alienage |

| Intermediate scrutiny applied when | A statute discriminates against, negatively affects, or creates a classification affecting certain protected classes |

| Rational basis review applied when | A law is challenged as irrational or arbitrary or involves discrimination based on age, disability, wealth, or felony status |

What You'll Learn

Strict scrutiny

In the context of the First Amendment, strict scrutiny is applied to content-based and viewpoint-based laws that restrict freedom of speech. The government must demonstrate a compelling interest in the law and that it is the least speech-restrictive means available. For example, in Ashcroft v. ACLU (2004), the Supreme Court struck down the Child Online Protection Act because, while the government had a compelling interest in protecting minors from harm, the law's restrictions on free speech were not the least restrictive means available.

The application of strict scrutiny can result in the invalidation of challenged classifications or laws. For example, in Loving v. Virginia (1967), the Supreme Court unanimously struck down Virginia's miscegenation law, which prohibited interracial marriage, as a clear violation of equal protection.

US Law Degrees: Which Apply in Ireland?

You may want to see also

Intermediate scrutiny

For a law to pass intermediate scrutiny, it must serve an important government objective and be substantially related to achieving that objective. This test was first accepted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1976 to be used when a law discriminates based on gender or sex. The burden of proof falls on the government, which must prove that the law or policy being challenged furthers an important government interest by means that are substantially related to that interest.

Restrictions based on illegitimacy are also subjected to intermediate scrutiny in the Equal Protection context. Courts have found this necessary for a number of reasons, including that an illegitimate person's status of birth is a condition over which they have no control and it has no bearing on their ability or willingness to contribute to society.

In recent decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court has preferred the term "exacting scrutiny" when referring to the intermediate level of Equal Protection analysis.

Wolff's Law: Post-Amputation Bone Health and Adaptation

You may want to see also

Rational basis review

Under the rational basis test, the person challenging the law (not the government) must prove either that the government has no legitimate interest in the law or policy, or that there is no reasonable, rational link between that interest and the challenged law. Courts using this test are highly deferential to the government and will often deem a law to have a rational basis as long as that law had any conceivable, rational basis—even if the government never provided one.

The rational basis test prohibits the government from imposing restrictions on liberty that are irrational or arbitrary, or drawing distinctions between persons in a manner that serves no constitutionally legitimate end. While a law "enacted for broad and ambitious purposes often can be explained by reference to legitimate public policies which justify the incidental disadvantages they impose on certain persons", it must nevertheless, at least, bear "a rational relationship to a legitimate governmental purpose".

Under rational basis review, it is entirely irrelevant what end the government is actually seeking and statutes can be based on "rational speculation unsupported by evidence or empirical data". If the court can merely hypothesize a "legitimate" interest served by the challenged action, it will withstand rational basis review. Judges following the Supreme Court's instructions understand themselves to be "obligated to seek out other conceivable reasons for validating" challenged laws if the government is unable to justify its own policies.

Slander Laws: US Congress' Freedom or Restraint?

You may want to see also

Suspect classifications

There are four generally agreed-upon suspect classifications: race, religion, national origin, and alienage. However, this is not an exhaustive list. In United States v. Carolene Products, Co., the Supreme Court encapsulates this feature through the concept of "discrete and insular minorities". These are individuals that are so disfavoured and out of the political mainstream that the courts must make extra efforts to protect them because the political system will not.

The use of suspect classifications is reviewed by the courts when the government action has a disproportionate or disparate impact on a particular group. For example, in Village of Willowbrook v. Olech (2000), the court reviewed the use of suspect classifications. Additionally, Washington v. Davis required that the impact on this particular group be intentional, in the sense that it results from a discriminatory purpose or design.

When a statute discriminates against an individual based on a suspect classification, that statute will usually be subject to either strict scrutiny or intermediate scrutiny. To pass strict scrutiny, the law or policy must satisfy a compelling government interest and be narrowly tailored to satisfy that interest.

In determining whether someone is a "discrete and insular minority", courts will look at a variety of factors, including but not limited to whether the person has an inherent trait, whether the person is part of a class that has been historically disadvantaged, and whether the person is part of a group that has historically lacked effective representation in the political process.

The Supreme Court has recognised race, national origin, and religion as suspect classes. It therefore analyses any government action that discriminates against these classes under strict scrutiny.

Privacy Laws: Do They Bind Corporations?

You may want to see also

Protected classes

The term "protected class" refers to a group of people who share a common characteristic and are legally protected from discrimination on the basis of that characteristic. Protected classes are established by federal and state laws, and policies vary by jurisdiction. Here is a detailed overview of protected classes:

- National origin or ancestry: It is illegal to discriminate against someone based on their country of origin, ethnicity, or lineage. This includes accent and language.

- Sex and gender: Federal law protects individuals from discrimination based on their biological sex, including male, female, and intersex. It also covers gender identity, expression, and non-conforming identities such as transgender, non-binary, and genderfluid.

- Sexual orientation: This includes protection for individuals who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, or asexual, among other orientations.

- Pregnancy and related conditions: Women are protected from discrimination during pregnancy, childbirth, and related medical conditions.

- Disability: People with physical or mental impairments that substantially limit major life activities are protected. This includes episodic or past impairments and even the perception of having an impairment.

- Genetic information: Discrimination based on genetic testing, family medical history, or the manifestation of a disease or disorder within a family is prohibited.

While federal law establishes a baseline, some states have expanded their protected classes. For example, in Ohio, the following classes are protected:

- Age: People over the age of 40 are protected from age-based discrimination.

- Religion or lack thereof: This includes various faiths such as Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Atheism, and Agnosticism.

- Race and colour: Protected classes include groups of people with shared physical characteristics, such as skin colour, hair texture, or facial features.

- Military and veteran status: Those who have served, are serving, or will serve in the military are protected. This also includes specific protections for disabled veterans and those with campaign badges.

- HIV/AIDS status: Individuals with HIV or AIDS, or those perceived to have these conditions, are protected.

- Other classifications: State laws may also protect against discrimination based on attributes such as wealth, felony status, or mental disability.

Application of Scrutiny Levels to Protected Classes:

When it comes to the levels of scrutiny applied to protected classes, the following patterns emerge:

- Strict scrutiny is often applied to cases involving race, national origin, religion, and alienage.

- Intermediate scrutiny is typically applied to gender- or sex-based discrimination and has also been used in cases involving sexual orientation.

- Rational basis review, the lowest level of scrutiny, is applied to age, disability, wealth, or felony status. However, this level of scrutiny has been criticised for being too lax and allowing laws to pass as constitutional without much scrutiny.

Briffault's Law: Family Dynamics and Female Empowerment

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Strict scrutiny is the highest standard of review that a court will use to evaluate the constitutionality of government action. It is applied when a law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right or involves a suspect classification, such as race or religion. The burden of proof falls on the government, which must demonstrate that the law is "narrowly tailored" to achieve a "compelling government interest" and that it uses the "least restrictive means" to achieve that purpose.

Intermediate scrutiny is the next level of judicial focus on challenged laws and is considered less demanding than strict scrutiny. It is invoked when a state or the federal government passes a statute that discriminates against, negatively affects, or creates some kind of classification affecting certain protected classes. The law must further an important government interest and be substantially related to achieving that interest.

Rational basis review is the lowest level of scrutiny applied to challenged laws. Under this standard, the person challenging the law (not the government) must prove either that the government has no legitimate interest in the law or that there is no reasonable, rational link between that interest and the challenged law. Courts are highly deferential to the government under this standard.