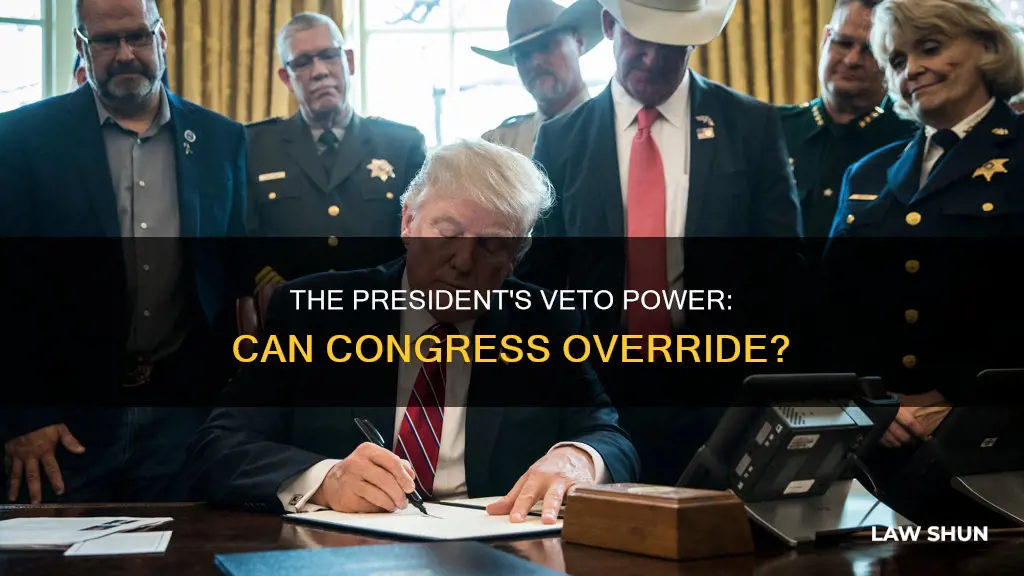

The process of a bill becoming a law in the United States involves the President having the power to veto it. If the House and Senate pass the same bill, it is sent to the President for review. The President must sign the bill within 10 days, or it becomes law without their signature. However, if the President vetoes the bill, it is sent back to Congress with a note listing their reasons for doing so. For the veto to be overridden, a two-thirds majority vote is required in both Houses of Congress, and if this occurs, the bill becomes law without the President's signature.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Who can veto a bill passed by Congress | The President of the United States |

| Time limit for the President to veto | 10 days (Sundays excepted) |

| What happens if the President does not veto within the time limit | The bill becomes law without the President's signature |

| What happens if Congress adjourns before the time limit | The bill does not become law |

| What happens if the President vetoes | The bill is sent back to Congress with a note listing the President's objections |

| What happens if Congress overrides the veto | The bill becomes law without the President's signature |

What You'll Learn

The President's veto power

The President has 10 days to veto or sign a bill. If the President does not act within this time frame, the bill becomes law unless Congress has adjourned before the 10 days are up—this is called a "pocket veto". In this case, the bill does not become law, and Congress must reintroduce it and enact it again if they want it to become law. The pocket veto was the subject of a 1929 Supreme Court case, which held that the President could not return a bill to the Senate when Congress adjourned fewer than 10 days after presenting the bill to the President. A later case in 1938 clarified that the President could return a bill to the originating Chamber during an intrasession adjournment, as long as there was no practical difficulty in making the return.

If the President returns a vetoed bill to Congress, it goes back to the chamber where it originated, and that chamber can attempt to override the veto by a two-thirds vote. If the veto is overridden, the bill is sent to the other chamber, which can also override the veto by a two-thirds vote, after which it becomes law.

Law Partners' K1 and QBI: What's the Verdict?

You may want to see also

Congressional override of a veto

The President of the United States has the authority to veto bills passed by Congress. This power is granted by Article I, Section 7 of the US Constitution. The veto is a significant tool that allows the President to prevent the passage of legislation, and even the threat of a veto can lead to changes in the content of a bill before it reaches the President's desk.

There are two types of vetoes: the "regular veto" and the "pocket veto." In a regular veto, the President returns the unsigned bill to the originating house of Congress within 10 days, along with a memorandum of disapproval or a "veto message." Congress can override a regular veto by a two-thirds vote in both the House and the Senate, which is known as a "congressional override."

The first successful congressional override occurred on March 3, 1845, during the waning hours of the 28th Congress. The House and the Senate joined to override President John Tyler's veto of an appropriation bill, with the House voting 126-31 in favor of the override. This was the first time Congress had successfully overruled a presidential veto.

A pocket veto occurs when the President does not sign a bill and Congress adjourns before the 10-day period is up. In this case, the bill does not become law, and the veto cannot be overridden by Congress. The pocket veto is considered an absolute veto.

Minors and Lawsuits: Can Children File Cases?

You may want to see also

The Presentment Clause

The clause further outlines the process for overriding a presidential veto. If two-thirds of both the House and the Senate vote to override the veto, the bill becomes law, even without the President's approval. This mechanism ensures that Congress can counterbalance the President's power if necessary.

The inclusion of the Presentment Clause in the Constitution was intentional, aiming to prevent legislative encroachment on executive power and encourage careful lawmaking. It also serves as a tool for the President to exercise power in foreign affairs. The veto power granted by this clause has been a subject of debate, with some arguing for the inclusion of a line-item veto, which would allow the President to veto specific provisions within a bill while approving the rest. However, others disagree, stating that the line-item veto could unconstitutionally burden the veto power and delegate excessive authority to the President.

The Bishop's Authority: Changing Canon Law?

You may want to see also

The Pocket Veto

The first president to use the pocket veto was James Madison in 1812. Franklin D. Roosevelt had an outstanding number of pocket vetoes, with 263 out of 635 of his vetoes being pocket vetoes. All presidents after him until George W. Bush had pocket vetoes while they were in office. Since the George W. Bush presidency, no president has used the pocket veto.

Law Firm S-Corp Formation in New York

You may want to see also

Presidential approval of a bill

The process of a bill becoming a law in the United States involves several steps, and the president has a crucial role in this process. Once a bill has been passed by both the House of Representatives and the Senate, it is presented to the President for approval.

The President has the power to approve or veto a bill. If the President approves of the bill, they are required to sign it into law. According to the Presentment Clause, the President need not write the word "approved" or the date of approval on the bill; their signature is sufficient. The President has ten days, excluding Sundays, to sign the bill. If the President does not sign the bill within this timeframe and Congress is still in session, the bill automatically becomes law without the President's signature.

However, if Congress adjourns before the ten days are up and the President has not signed the bill, it does not become law. This is known as a "pocket veto." In the case of a pocket veto, the bill is not enacted, and Congress cannot override this type of veto.

On the other hand, if the President vetoes the bill, it is sent back to Congress with a note listing their reasons for doing so. The chamber where the bill originated can then attempt to override the veto by a vote of two-thirds of those present. If both chambers override the veto by a two-thirds vote, the bill becomes law, even without the President's approval.

Martial Law: Presidential Inauguration Amidst Unrest

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The President of the United States can veto a bill which Congress passes.

When the President vetoes a bill, it is sent back to Congress with a note listing their reasons for doing so.

Yes, if two-thirds of both the House and the Senate vote to override the veto, the bill becomes law without the President's signature.