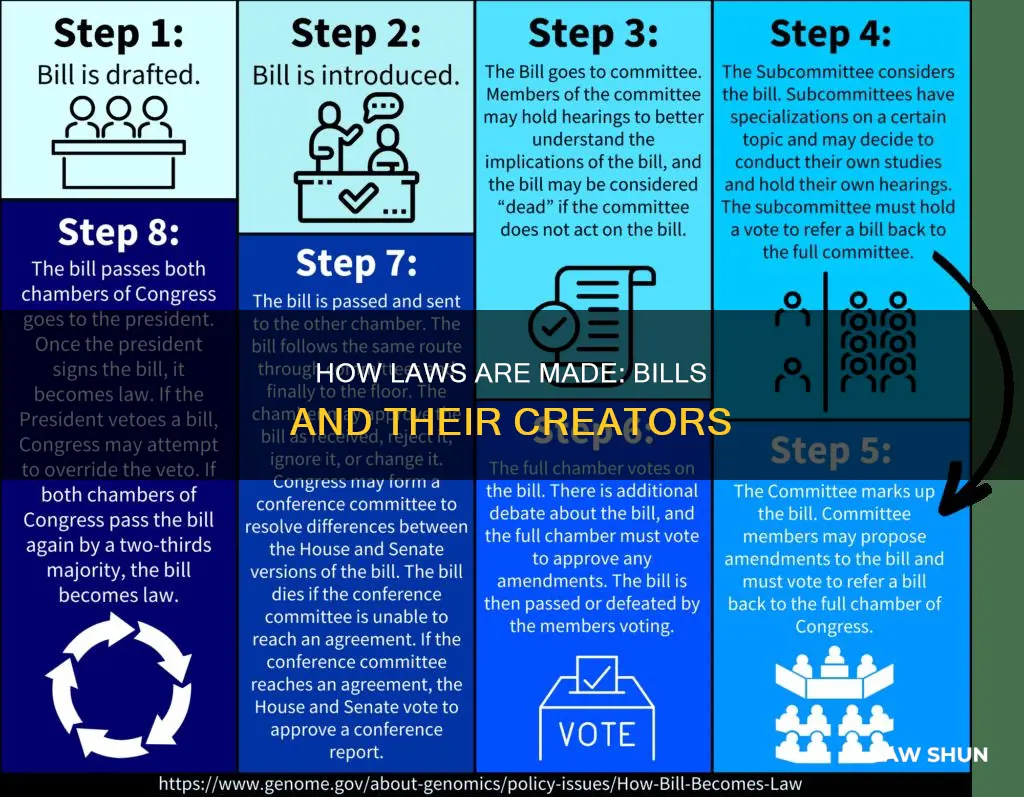

The process of turning a bill into a law is a long and complex one, with many steps and potential setbacks. In the US, the lawmaking branch of the federal government is Congress, which is made up of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The idea for a bill can come from a sitting member of the Senate or House of Representatives, or be proposed during their election campaign. Bills can also be petitioned by citizens or citizen groups who recommend a new or amended law to a member of Congress. Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee, whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill. The bill is then put before that chamber to be voted on. If the bill passes one body of Congress, it goes to the other body to go through a similar process of research, discussion, changes, and voting. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must work out any differences between the two versions. Then both chambers vote on the same version of the bill. If it passes, they present it to the president.

The president then has the choice to approve the bill and sign it into law, or refuse to approve it, which is called a veto. If the president chooses to veto a bill, Congress can vote to override that veto, and the bill becomes a law. However, if the president does not sign off on a bill and it remains unsigned when Congress is no longer in session, the bill will be vetoed by default, which is called a pocket veto.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Who can write the first draft of a bill? | Any member of Congress or everyday citizens and advocacy groups |

| Who introduces the bill? | A Representative or a Senator, depending on who the sponsor is |

| Who assigns a number to the bill? | A bill clerk |

| Who votes on the bill? | The U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate |

| Who has the final say on the bill? | The President of the United States |

What You'll Learn

- Bills are drafted by members of Congress, who can be influenced by citizens and advocacy groups

- Bills are introduced in the House or Senate, depending on the sponsor

- Bills are assigned to committees, who review, research and revise them

- Bills are voted on by the full chamber

- Bills are sent to the President to be signed into law or vetoed

Bills are drafted by members of Congress, who can be influenced by citizens and advocacy groups

The bill then needs a sponsor. The representative talks with other representatives about the bill in the hopes of getting their support. Once a bill has a sponsor and the support of some of the other representatives, it is ready to be introduced. In the U.S. House of Representatives, a bill is introduced when it is placed in the hopper—a special box on the side of the clerk's desk. Only representatives can introduce bills in the U.S. House of Representatives. When a bill is introduced, a bill clerk assigns it a number. For example, a bill originating in the House of Representatives is designated by 'H.R.' followed by a number.

The Speaker of the House then sends the bill to one of the House standing committees. These committees are groups of representatives who are experts on topics such as agriculture, education, or international relations. When a bill reaches a committee, the committee members review, research, and revise the bill before voting on whether or not to send it back to the House floor. If the committee members would like more information before deciding, the bill is sent to a subcommittee. While in the subcommittee, the bill is closely examined and expert opinions are gathered before it is sent back to the committee for approval.

Once the committee has approved a bill, it is sent, or reported, to the House floor. Once reported, a bill is ready to be debated by the U.S. House of Representatives. Representatives discuss the bill and explain why they agree or disagree with it. Then, a reading clerk reads the bill section by section, and the representatives recommend changes. When all changes have been made, the bill is ready to be voted on.

History of DWI Laws: When Did They Come Into Force?

You may want to see also

Bills are introduced in the House or Senate, depending on the sponsor

In the Senate, a bill is typically submitted to clerks on the Senate floor. Upon introduction, the bill will receive a designation based on the chamber of introduction, for example, H.R. or H.J.Res. for House-originated bills or joint resolutions and S. or S.J.Res. for Senate-originated measures. It will also receive a number, which is usually the next number available in sequence during that two-year Congress.

In the House, bills are then referred by the Speaker, on the advice of the nonpartisan parliamentarian, to all committees that have jurisdiction over the provisions in the bill, as determined by the chamber's standing rules and past referral decisions. Most bills fall under the jurisdiction of one committee. If multiple committees are involved and receive the bill, each committee may work only on the portion of the bill under its jurisdiction. One of those committees will be designated the primary committee of jurisdiction and will likely take the lead on any action that may occur.

In the Senate, bills are typically referred to a committee in a similar process, though in almost all cases, the bill is referred to only the committee with jurisdiction over the issue that predominates in the bill. In a limited number of cases, a bill might not be referred to a committee but instead be placed directly on the Senate Calendar of Business through a series of procedural steps on the floor.

The Nuremberg Code: From Ethics to Law

You may want to see also

Bills are assigned to committees, who review, research and revise them

Once a bill has been introduced, it is assigned to a committee. Committees are groups of members appointed to investigate, debate, and report on legislation. They are not mentioned in the Constitution but have become an important part of the legislative process since their introduction during the first Congress in 1789. There are five types of committees: standing committees, subcommittees, select committees, joint committees, and the Committee of the Whole.

Standing committees are the most common type of committee and consider bills and other legislation that is before the U.S. House of Representatives. When a bill is introduced on the House floor, it is assigned a bill number and sent to a standing committee by the Speaker of the House. There are currently 20 standing committees, each covering a different area of public policy.

While in committee, a bill is reviewed, researched, and revised. Committee members may hold a committee hearing to receive testimony and view evidence to gather as much information as possible about the bill. Once the committee members are satisfied with the bill, they vote on whether or not to report it to the House floor for consideration by the full U.S. House of Representatives.

Each member, delegate, and resident commissioner in the U.S. House of Representatives serves on two standing committees. Committee assignments are given at the start of each new Congress. Members can request to serve on specific committees. Returning members usually keep their committee assignments from the previous Congress because they have expertise and seniority.

A special "committee on committees" matches members' requests with the available committee positions. These assignments are approved by the majority and minority parties before being brought before the full Chamber for approval. Once assigned to a committee, members must develop expertise in the committee's content area, vote on motions, prepare and vote on amendments, decide whether or not to report bills to the House floor, and write committee reports and studies.

Many committees, usually standing committees, have smaller subcommittees within them. The members of these subcommittees have expertise in a specific part of a committee's area of public policy. Like standing committees, subcommittees hold hearings, conduct research, and revise bills. Subcommittees report bills back to the full committee rather than the House floor.

Select committees are temporary committees created with a timeline to complete a specific task, like investigating government activity. Rather than researching and reporting bills to the House floor, they research specific issues or oversee government agencies.

Joint committees include members from both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. Joint committees debate and report on matters concerning Congress rather than issues of public policy. Because they consider only matters affecting Congress, such as organizing the Presidential Inauguration ceremonies, they do not consider legislation or report on legislation to either the U.S. House of Representatives or the U.S. Senate.

The Committee of the Whole is a way to move legislation through to the House floor for a vote quickly. The Committee of the Whole is able to debate bills more efficiently than the full U.S. House of Representatives because it requires a smaller quorum—only 100 members versus the 218 required of the full House.

The SDWA: Federal Law Journey and Implementation

You may want to see also

Bills are voted on by the full chamber

Once a bill has been introduced, it is assigned to a committee whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill. This is where the bill is first voted on.

The committee is made up of groups of representatives who are experts on topics such as agriculture, education, or international relations. They will review, research, and revise the bill before voting on whether or not to send it back to the House floor. If the committee members would like more information before deciding, the bill is sent to a subcommittee. While in subcommittee, the bill is closely examined and expert opinions are gathered before it is sent back to the committee for approval.

Once the committee has approved a bill, it is sent—or reported—to the House floor. Once reported, a bill is ready to be debated by the full chamber.

When a bill is debated, representatives discuss the bill and explain why they agree or disagree with it. Then, a reading clerk reads the bill section by section and the representatives recommend changes. When all changes have been made, the bill is ready to be voted on by the full chamber.

Business Law Attorney: Steps to Take for a Career

You may want to see also

Bills are sent to the President to be signed into law or vetoed

Once a bill has been passed by both chambers of Congress, it is sent to the President for review. The President has ten days, excluding Sundays, to sign or veto the bill. If the bill is signed within this ten-day period, it becomes law. If the President declines to sign or veto the bill, it becomes law without their signature unless Congress has adjourned under certain circumstances. This is known as a "pocket veto".

If the President vetoes the bill, it is returned to the chamber in which it originated. This chamber may then attempt to override the President's veto, though this requires the support of two-thirds of those voting. If this attempt is successful, the bill is sent to the other chamber, which can then vote to override the veto. Only if both chambers vote to override does the bill become law, notwithstanding the President's veto.

The Legislative Process: How a Bill Becomes Law

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ideas for a bill can come from a sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, be proposed during their election campaign, or be petitioned by citizens or citizen groups.

The first step is for the bill to be introduced. In the U.S. House of Representatives, this happens when the bill is placed in the hopper, a special box on the side of the clerk's desk.

Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill.

If the President chooses to veto a bill, in most cases, Congress can vote to override that veto and the bill becomes a law.