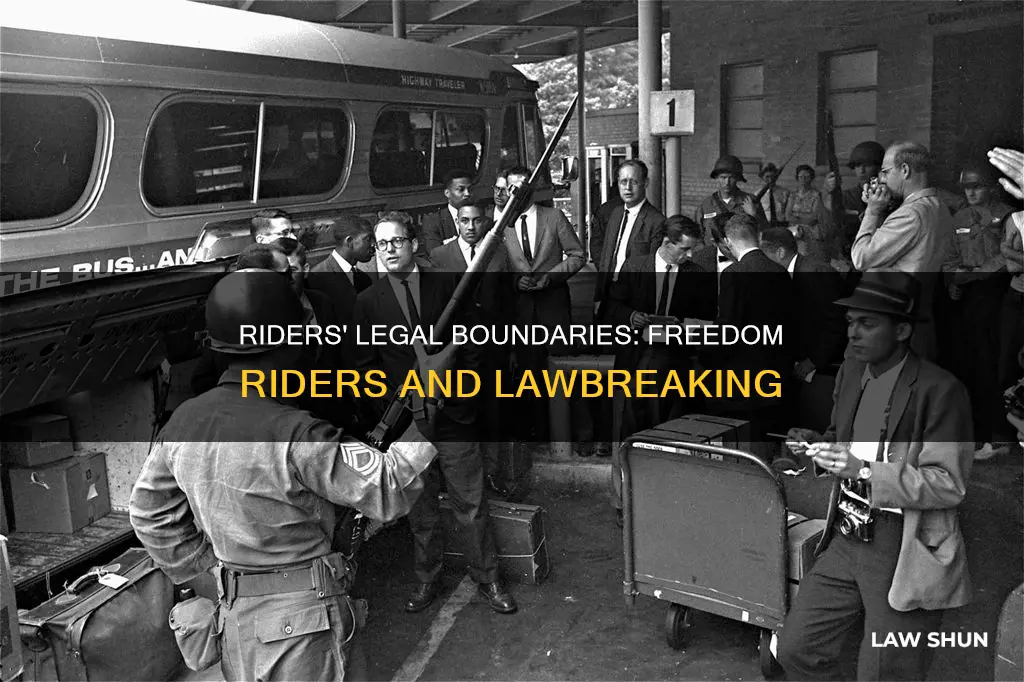

The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Freedom Riders challenged this status quo by riding interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. The Freedom Riders' tactics for their journey were to have at least one interracial pair sitting in adjoining seats, and at least one black rider sitting up front, where seats under segregation had been reserved for white customers by local custom throughout the South. The rest of the team would sit scattered throughout the rest of the bus. The Freedom Riders were arrested for trespassing, unlawful assembly, violating state and local Jim Crow laws, and other alleged offenses, but often the police would let white mobs attack them without intervention.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date | 1961 |

| Participants | Civil rights activists, including college students |

| Purpose | Challenge segregation on interstate buses and in terminals |

| Actions | Rode buses, used "whites-only" facilities, and sang freedom songs in jail |

| Response | Violence from white protestors, arrests by police, and international attention |

| Outcome | Interstate Commerce Commission ban on segregation in facilities under their jurisdiction |

What You'll Learn

Freedom Riders' actions in bus terminals

The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Southern states had ignored the rulings, and the federal government did nothing to enforce them.

The Freedom Riders challenged this status quo by riding interstate buses in the South in mixed-race groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. The Freedom Rides, and the violent reactions they provoked, bolstered the credibility of the American Civil Rights Movement. They called national attention to the disregard for federal law and the local violence used to enforce segregation in the southern United States.

The Freedom Riders' tactics for their journey were to have at least one interracial pair sitting in adjoining seats, and at least one Black rider sitting up front, where seats under segregation had been reserved for white customers by local custom throughout the South. The rest of the team would sit scattered throughout the rest of the bus. One rider would abide by the South's segregation rules in order to avoid arrest and to contact the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and arrange bail for those who were arrested.

The Freedom Riders' actions in bus terminals included attempting to use whites-only restrooms and lunch counters at bus stations in Alabama, South Carolina, and other Southern states. They were confronted by arresting police officers and horrific violence from white protestors along their routes.

On May 14, 1961, a Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders was attacked in Anniston, Alabama, by a mob of about 200 white people, who threw a bomb into the bus, causing it to burst into flames. The Freedom Riders escaped the bus but were brutally beaten by the mob.

The same day, Freedom Riders on a Trailways bus were beaten bloody after they entered whites-only waiting rooms and restaurants at bus terminals in Birmingham and Anniston, Alabama. The police cooperated with the Ku Klux Klan and allowed the mobs to attack the riders.

In Montgomery, Alabama, a white mob attacked the Freedom Riders with baseball bats and iron pipes as they disembarked from the bus. The local police allowed the beatings to go on uninterrupted.

In Jackson, Mississippi, Freedom Riders were arrested when they tried to use the white-only facilities at the Tri-State Trailways depot. This established a pattern followed by subsequent Freedom Rides, most of which travelled to Jackson, where the Riders were arrested and jailed.

Bashir's Law: Crossing Lines in Journalism

You may want to see also

Police involvement in the Freedom Rides

Police Arrests and Lack of Intervention

The Freedom Riders, a group of civil rights activists, challenged the non-enforcement of Supreme Court decisions that ruled segregated public buses unconstitutional. They rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States, particularly Alabama, South Carolina, and other Southern states, to protest bus terminal segregation. While the Freedom Rides were met with violent reactions from white protestors, they also drew international attention to the civil rights movement.

Police officers often arrested the Freedom Riders for various offenses, including trespassing, unlawful assembly, and violating state and local Jim Crow laws. However, in some instances, the police failed to intervene and allowed white mobs to attack the Freedom Riders without consequence. This was particularly evident in Birmingham, Alabama, where the police cooperated with the Ku Klux Klan and allowed mobs to assault the riders without interference.

Police Cooperation with Segregationists

In Birmingham, Alabama, Police Commissioner Bull Connor and Police Sergeant Tom Cook, an avid Ku Klux Klan supporter, organized violence against the Freedom Riders. They assured Gary Thomas Rowe, an FBI informant and member of a violent Klan group, that the mob would have uninterrupted time to attack the Freedom Riders. Connor also admitted that he posted no police protection at the station during the Mother's Day attack, knowing full well that violence awaited the riders.

Police Escort and Federal Intervention

Despite the violent incidents and police involvement, the Freedom Rides continued with police escort and federal intervention. U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, brother of President John F. Kennedy, negotiated with Alabama's governor and bus companies to secure a driver and state protection for the Freedom Riders. The rides resumed with a police escort, but the police abandoned the Greyhound bus before it arrived at the Montgomery, Alabama, terminal, where a white mob attacked the riders.

Police Inaction and Mob Violence

In Montgomery, Alabama, the local police did nothing to stop the beatings inflicted by the white mob. Reporters and news photographers were among the first targets of the mob, and their cameras were destroyed. The violence escalated to the point where Attorney General Kennedy had to send 600 federal marshals to the city to restore order. Governor Patterson was forced to declare martial law and dispatch the National Guard to control the situation.

Police Apologies and Reconciliation

Decades later, in 2013, Montgomery Police Chief Kevin Murphy apologized to Freedom Rider and U.S. Congressman John Lewis for the department's failure to protect them during the violent incidents. This reconciliation occurred during commemorative events in Montgomery, highlighting a long-overdue recognition of police misconduct during the Freedom Rides.

In conclusion, police involvement in the Freedom Rides was a complex and often contradictory aspect of the civil rights movement. While some officers made efforts to protect the Freedom Riders, others actively cooperated with segregationists or turned a blind eye to violent attacks. The Freedom Rides brought widespread attention to racial injustice and prompted federal intervention, but they also exposed the deep-seated racism and inaction within law enforcement agencies in the South.

Businesses Hiring Undocumented Workers: Is It Legal?

You may want to see also

Violence against Freedom Riders

The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Freedom Rides were organised by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and modelled after the organisation's 1947 Journey of Reconciliation.

The Freedom Riders faced violent reactions from white protestors and police officers along their routes. Here is a detailed account of the violence inflicted on the Freedom Riders:

Violence in Rock Hill, South Carolina

The first violent incident occurred on May 12, 1961, in Rock Hill, South Carolina. John Lewis, an African American seminary student and member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), was attacked by two men as he attempted to enter a whites-only waiting area. Lewis was battered in the face and kicked in the ribs.

Violence in Anniston, Alabama

On May 14, 1961, a Greyhound bus carrying Freedom Riders was surrounded by an angry mob of about 200 white people in Anniston, Alabama. The mob slashed the bus tires and threw a bomb into the bus, causing it to burst into flames. The Freedom Riders narrowly escaped the burning bus but were brutally beaten by the mob.

Violence in Birmingham, Alabama

The same day, a Trailways bus carrying Freedom Riders arrived in Birmingham, Alabama, where they faced another angry mob. The riders were beaten with baseball bats, iron pipes, bicycle chains, and other weapons. Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor admitted that he posted no police protection at the station, despite knowing that violence awaited the Freedom Riders.

Violence in Montgomery, Alabama

On May 20, 1961, a bus carrying Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery, Alabama, from Birmingham. A white mob was waiting at the bus station and beat the riders with baseball bats and iron pipes as they disembarked. The local and state police made little effort to contain the violence.

Violence in Jackson, Mississippi

On May 24, 1961, a group of Freedom Riders departed Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi. Upon arrival, they were arrested for trespassing when they attempted to use whites-only facilities at the station. The Freedom Riders were subjected to abusive treatment and placed in the Maximum Security Unit of the Mississippi State Penitentiary.

The violent reactions against the Freedom Riders brought international attention to the civil rights movement and the state of race relations in the United States.

Understanding Mandatory Breaks During 12-Hour Work Shifts

You may want to see also

The Freedom Rides' legacy

The Freedom Rides were a pivotal moment in the history of the American Civil Rights Movement. The Rides, and the violent reactions they provoked, bolstered the credibility of the movement and brought national attention to the disregard for federal law and the local violence used to enforce segregation in the southern United States.

The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional.

The Freedom Rides had two important outcomes. Firstly, due to pressure from Robert Kennedy's Justice Department, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) declared an end to racial segregation in all waiting rooms and lunch counters, effective from November 1, 1961. Although not everyone immediately followed this rule, it sent a clear message to southern whites that desegregation of other institutions was likely to happen soon.

Secondly, the widespread violence in response to the Freedom Rides sent shock waves through American society. People were worried that the Rides were evoking widespread social disorder and racial divergence, an opinion supported and strengthened in many communities by the press. At the same time, the Rides established great credibility with black and white people throughout the United States and inspired many to engage in direct action for civil rights.

The Freedom Riders' legacy is that they developed an approach they consistently and genuinely honoured. Their enduring inspiration is that they lighted the way to the power of a dream fearlessly pursued. They showed what people connected by a common purpose to do good can accomplish together.

The Freedom Rides demonstrated the possibility that an organization can create a spirit, a common purpose, and a passion that can infuse followers, turning them into a community capable of doing great things. The Freedom Riders created a community that fuelled them, even during the worst experiences. They embraced a code of conduct that also became an operational strategy. For their purpose, it was nonviolence. Their tactics and strategy were consistent and made sense based on who they said they were. They knew what they wanted to accomplish and they delivered on that goal with discipline and authenticity.

The Freedom Riders gained strength from the clarity of their mission, how well prepared they were to go after it, and the system of support that developed in serving a higher purpose.

The Monster and the Law: Dr. Frankenstein's Legal Woes

You may want to see also

The Freedom Rides' legality

The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and modelled after the organization's 1947 Journey of Reconciliation.

The Freedom Riders challenged the status quo by riding interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. They also attempted to use whites-only restrooms, lunch counters, and waiting rooms in bus terminals in Alabama, South Carolina, and other Southern states. These actions were in direct violation of the Jim Crow travel laws that were still in force throughout the South.

The Freedom Riders' tactics included having at least one interracial pair sitting in adjoining seats, and at least one Black rider sitting up front, where seats had been reserved for white customers under segregation. The rest of the team would sit scattered throughout the rest of the bus. One rider would abide by the South's segregation rules to avoid arrest and to contact CORE to arrange bail for those who were arrested.

The Freedom Riders' actions were considered criminal by Southern local and state police, who arrested them for trespassing, unlawful assembly, violating state and local Jim Crow laws, and other alleged offenses. The riders also faced violent reactions from white protestors, including being beaten, firebombed, and attacked with weapons such as baseball bats, pipes, and brass knuckles.

Despite the legal consequences and violent reactions they faced, the Freedom Rides continued over several months and ultimately succeeded in securing an Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) ban on segregation in all facilities under their jurisdiction. This outcome demonstrated the impact of the Freedom Riders' actions in challenging the legality of segregation and advancing the civil rights movement.

Ester's Legal Quandary: Crossing the Line?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Freedom Riders were arrested for trespassing, unlawful assembly, and violating state and local Jim Crow laws. However, the laws they were protesting were deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

Freedom Rides were bus trips through the American South in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals. The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions that ruled segregated public buses were unconstitutional.

The Freedom Rides brought national attention to the civil rights movement and the state of race relations in the United States. They also led to the Interstate Commerce Commission issuing regulations prohibiting segregation in interstate transit terminals.