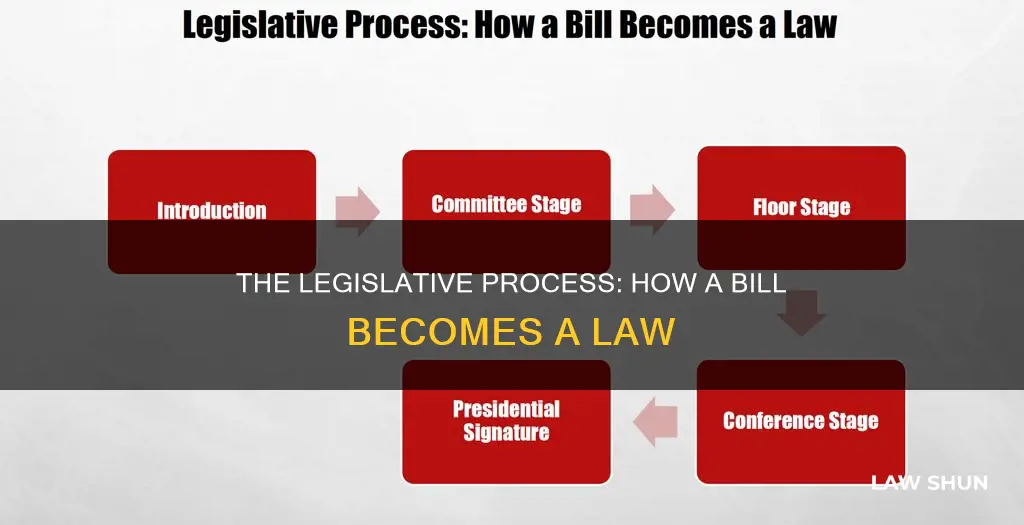

The process of how a bill becomes a law is complex and lengthy. It involves a series of amendments, votes, committees, and floor votes in both houses of Congress before potentially reaching the President's desk. Even if a bill passes both houses, it can still be vetoed by the President, and if not vetoed, it must be signed into law within 10 days. This intricate journey from bill to law is the focus of the Crash Course episode, which aims to shed light on the challenging path towards enacting legislation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Where does a bill start? | As an idea from a congressman, a senator, their constituents, an interest group, or the executive branch |

| Where does the bill go once it is introduced? | A relevant committee |

| Where does the bill go if it gets a majority vote in a committee in the Senate? | It is voted to be an "open rule" (amendments allowed) or a "closed rule" debate, and then it goes to the House if it gets a majority vote |

| Where does the bill go if it gets a majority vote in the Senate? | It goes to the Rules Committee of the House before it can get to the floor |

| What happens if one house of Congress isn't happy with the bill from the other side? | It heads to a conference committee, which is composed of members of both houses, who come up with a compromised bill that will try to pass both houses again |

| What happens if a bill is vetoed by the president? | It's dead unless it gets a 2/3 vote in both houses |

| What happens if the President neither signs nor vetoes a bill, and Congress is still in session for more than 10 days later? | It automatically becomes a law |

| How can a bill die? | The Speaker or Majority Leader can refuse to refer it to a committee; the committee can choose not to vote on it; it might not get a majority vote in the committee; the entire House can decide to recommit the bill to the committee, which means that it needs to be dropped or significantly changed; the Senate leadership can refuse to schedule a vote on it; senators can filibuster a bill; presidential veto |

What You'll Learn

Bill introduction

The bill introduction is the formal beginning of a bill. This is when a legislator, such as a congressman, congresswoman or senator, introduces a bill to a committee. The idea for a bill can come from an interest group, the executive branch, or even the constituents, but the formal process begins with the legislator.

Most bills can start in either the House of Representatives or the Senate, except for revenue bills, which must start in the House. A bill is then referred to a relevant committee, which will then write up the bill in formal, legal language, or markup, and vote on it. If the bill gets a majority vote in the committee, it moves to the floor of the full Senate for consideration.

The Senate decides the rules for debate, including how long the debate will go on and whether or not there will be amendments. An open rule allows for amendments, while a closed rule does not. Open rules make it less likely for a bill to pass because proponents of the bill can add clauses that will make it hard for the bill's supporters to vote for. If a bill wins the majority of the votes in the Senate, it moves on to the House.

Understanding Lawmaking: The Game of Bills and Laws

You may want to see also

Committee referral

Once a bill has been introduced by a congressperson, it is referred to a committee. In the case of our example bill about naming helicopters, it would be referred to the Senate Armed Services Committee. The committee will then write up the bill in formal, legal language, or markup, and vote on it. If the markup wins a majority in the committee, it moves to the floor of the full Senate for consideration.

The next step is for the Senate to decide the rules for debate, including how long the debate will go on and whether or not there will be amendments. An open rule allows for amendments, while a closed rule does not. Open rules make it less likely for a bill to pass because proponents of the bill can add clauses that will make it hard for the bill's supporters to vote for. For example, if opponents of the helicopter-naming bill added a clause repealing the Affordable Care Act, some supporters of the bill probably wouldn't vote for it.

If a bill wins the majority of the votes in the Senate, it moves on to the House. However, the House has an extra step: all bills must first go to the Rules Committee, which reports it out to the House. If the bill receives the majority of votes in the House—238 or more to be exact—it passes.

It's important to note that the exact same bill must pass both houses before it can go to the president. This almost never happens, as the second house will usually want to make changes. If this is the case, the bill will go to a conference committee made up of members from both houses. The conference committee will attempt to reconcile both versions of the bill and come up with a new version, sometimes called a compromise bill.

Game of Laws: Bill's Journey

You may want to see also

Amendments and votes

If the bill passes the committee with a majority vote, it moves to the floor of the full Senate for consideration. The Senate decides the rules for debate, including its duration and whether amendments are allowed. If the bill passes the Senate with a majority vote, it moves on to the House. The House has an extra step, as all bills must first go to the Rules Committee, which then reports it out to the House.

If the bill passes the House with a majority vote, it has successfully passed both houses. However, it is rare for the exact same bill to pass both houses. Usually, the second house will want to make some changes, in which case the bill will go to a conference committee made up of members from both houses. This committee will attempt to reconcile the two versions and come up with a compromise bill. If a compromise is reached, the bill is sent back to both houses for a new vote. If it passes, it is then sent to the President.

The President has three options: signing the bill into law, vetoing it, or, if it is the end of a congressional term, doing nothing for 10 days while Congress is still in session, resulting in a "pocket veto". If the President vetoes the bill, it can still become a law if it receives a two-thirds majority in both houses on a second vote.

Becoming an Elder Law Attorney: Steps to Specialization

You may want to see also

Presidential signature

Once a bill has successfully navigated the hurdles of both houses of Congress, it is sent to the President. The President has three options: they can sign the bill, veto it, or do nothing. If the President signs the bill, it becomes law.

If the President vetoes the bill, it is sent back to Congress, where it can be overridden if it achieves a two-thirds majority vote in both houses. This is a rare occurrence, as the President is unlikely to veto a bill if they know it has enough support to override their decision.

The third option, doing nothing, is known as a 'pocket veto'. This can only be used at the end of a congressional term. If the President neither signs nor vetoes the bill, and Congress goes out of session within ten days, the bill does not become law. This is a way for the President to effectively veto a bill without having to actually use their veto power, often for political reasons. However, Congress can avoid this outcome by ensuring the President receives the bill at least ten days before the end of the session. If the President does nothing and Congress remains in session for more than ten days, the bill becomes law without the President's signature.

The Legislative Process: A Comic Strip Guide

You may want to see also

Overriding a veto

The process of how a bill becomes a law is complex, with many opportunities for a bill to "die". Once a bill has passed through both houses of Congress, it is sent to the President, who has the power to veto it. A presidential veto, however, does not have to be the end of the road for a bill.

The veto power of the President acts as a “check” on the legislative branch, allowing the President to block measures they find unconstitutional, unjust, or unwise. The veto return process involves the President returning the bill, along with their objections, to the house in which it originated. The veto can be overridden by a two-thirds vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives, which acts as a “balance” to the President's powers. This is known as a veto override and results in the bill becoming law over the President's objections.

A pocket veto occurs when Congress adjourns during the ten-day period after passing a bill, and the President does not sign it. In this case, Congress does not have the opportunity to override. However, if Congress is still in session more than ten days after passing a bill, and the President has neither signed nor vetoed it, the bill automatically becomes law.

Veto overrides are rare, as the President typically will not veto a bill if they know it has enough support in Congress to override their decision. Similarly, Congress will not attempt to override a veto if they know they do not have enough support, as no one wants to fail publicly.

Understanding the Lawmaking Process: Bill to Law Simulation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first step is for a bill to be introduced by a congressman, a senator, or their constituents.

The bill is then handed over to a relevant committee.

It is voted to be an "open rule" (amendments allowed) or a "closed rule" (no amendments) debate, and then it goes to the House if it gets a majority vote.

It automatically becomes a law.