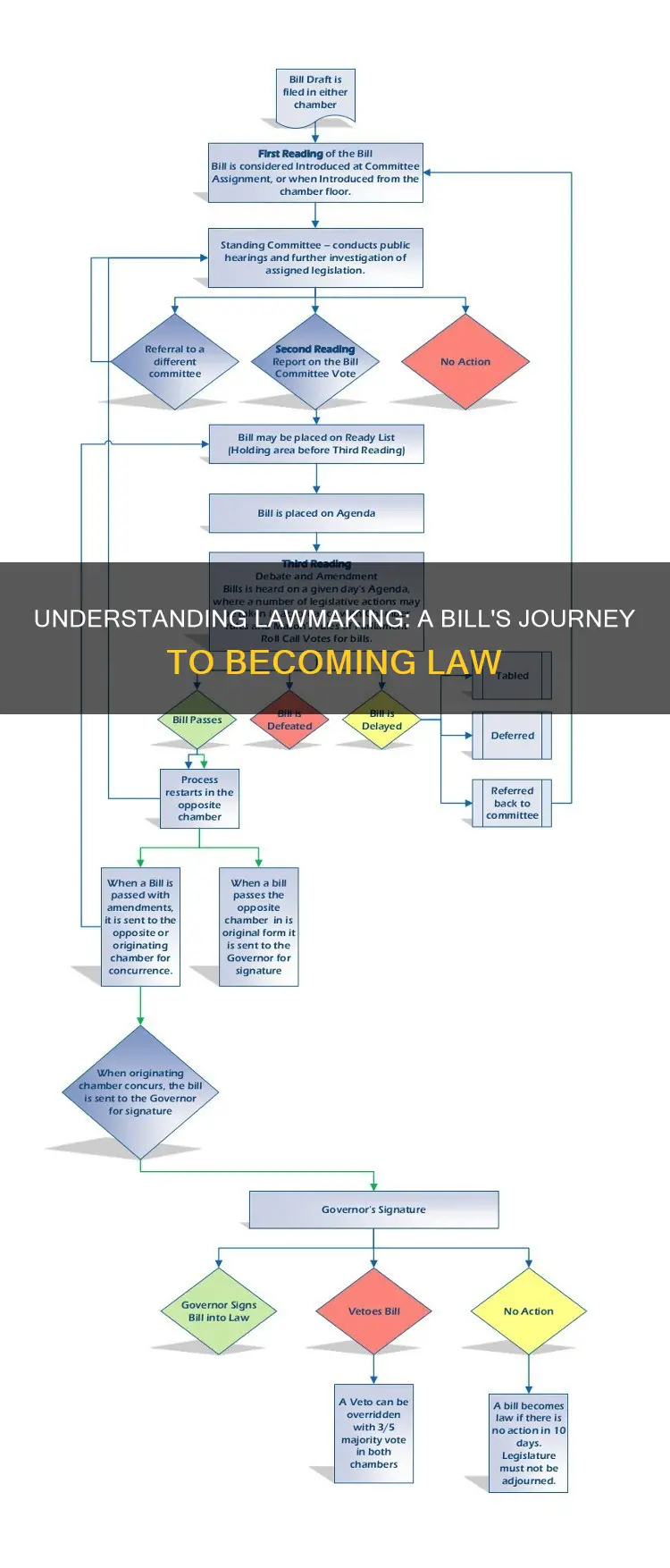

The process of how a bill becomes a law is a lengthy one and differs slightly between the House of Representatives and the Senate. All laws in the United States begin as bills, and the journey to becoming a law is a complex one. The idea for a bill can come from a citizen, a group of citizens, or a sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives. Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned a number and a sponsor, and then it is sent to a committee. The committee will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill before it is voted on. If the bill passes in one body of Congress, it goes to the other body to undergo a similar process. Once both bodies have voted to accept a bill, they must work together to create one version of the bill. This final version is then presented to the President, who can approve and sign the bill into law or veto it.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Creation of a Bill |

| Step 2 | Committee Action |

| Step 3 | Floor Action |

| Step 4 | Vote |

| Step 5 | Conference Committees |

| Step 6 | Presidential Action |

| Step 7 | The Creation of a Law |

What You'll Learn

Bill proposal and introduction

The idea for a bill can come from a sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, be proposed during their election campaign, or be petitioned by citizens or citizen groups who recommend a new or amended law to a member of Congress that represents them. Citizens who have ideas for laws can contact their Representatives to discuss their ideas. If the Representatives agree, they research the ideas and write them into bills.

Once a Representative has written a bill, it needs a sponsor. The Representative talks with other Representatives about the bill in the hopes of getting their support. Once a bill has a sponsor and the support of some of the Representatives, it is ready to be introduced.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, a bill is introduced when it is placed in the hopper, a special box on the side of the clerk's desk. Only Representatives can introduce bills in the U.S. House of Representatives. When a bill is introduced, a bill clerk assigns it a number that begins with H.R. It is then read by a reading clerk to all the Representatives, and the Speaker of the House sends the bill to one of the House standing committees.

In the Senate, the bill is submitted to clerks on the Senate floor. Upon introduction, the bill will receive a designation based on the chamber of introduction, for example, H.R. or H.J.Res. for House-originated bills or joint resolutions and S. or S.J.Res. for Senate-originated measures. It will also receive a number, typically the next number available in sequence during that two-year Congress.

Crafting the Bill

When drafting the bill, it is important to give it a strong title that will catch people's attention and generate interest. The bill should also have a brief statement explaining its objective, so that legislators can envision voting for it. The bill should also define the people who are covered by the proposed legislation, as well as any terms that have a particular meaning.

The bill should also state the rules and other provisions, or the requirements that are being proposed. This section should be clear and concise to avoid confusion or misunderstanding. The length and organization of this section will depend on the complexity of the issue. A simple bill may be a single sentence, while a more complex bill may need to be broken into sections and subsections.

Finally, the bill should address issues of funding and provide an effective date for when the legislation will come into force.

The Legislative Process: How Bills Become Laws

You may want to see also

Committee review

Once a bill has been introduced, it is assigned to a committee whose members will review, research, discuss, and make changes to the bill. Committees are usually assigned according to the bill's subject matter. For example, a bill about education would be reviewed by a committee of experts on education. The committee may refer the bill to one of its subcommittees, where experts and interested parties have an opportunity to offer testimony regarding the issue. The subcommittee may request reports from government agencies and hold hearings. The subcommittee may then "mark up" or revise the bill, or report the legislation to the full committee for its consideration.

The full committee may make a recommendation to pass the bill, to revise and release the bill (also known as reporting the bill out of the committee), or to lay the bill aside (also known as tabling the bill). If the bill is released from the committee, the committee staff prepares a written report explaining why they favor the bill and why they wish to see their amendments, if any, adopted. Committee members who oppose a bill sometimes write a dissenting opinion in the report. The report is sent back to the whole chamber and is placed on the calendar.

In the House, most bills go to the Rules Committee before reaching the floor. The Rules Committee adopts rules that will govern the procedures under which the bill will be considered by the House. A "closed rule", for example, sets strict time limits on debate and forbids the introduction of amendments. These rules can have a major impact on whether the bill passes. The Rules Committee can be bypassed in three ways: 1) members can move rules to be suspended (requiring a two-thirds vote); 2) a discharge petition can be filed; or 3) the House can use a Calendar Wednesday procedure.

The Veto Power: How a Bill Becomes Law

You may want to see also

Floor action

Once a bill has been reported, it is sent to the floor of the House of Representatives, where it is debated and voted on. During the debate, Representatives discuss the bill, explaining why they agree or disagree with it. A reading clerk then reads the bill section by section, and Representatives can recommend changes. When all changes have been made, the bill is ready to be voted on.

There are three methods for voting on a bill in the House of Representatives: Viva Voce (voice vote), Division, and Recorded. In a voice vote, the Speaker of the House asks those who support the bill to say "aye" and those who oppose it to say "no". In a Division vote, supporters of the bill are asked to stand up and be counted, and then the same is done for those who oppose it. In a Recorded vote, Representatives use an electronic voting system to record their vote as yes, no, or present if they don't want to vote on the bill. If a majority of Representatives vote yes, the bill passes in the House and is then delivered to the Senate.

The bill then goes through many of the same steps in the Senate. It is discussed in a Senate committee and then reported to the Senate floor for a vote. Senators vote by voice, saying "yea" if they support the bill and "nay" if they oppose it. If a majority of Senators say "yea", the bill passes in the Senate and is sent to the President.

The President has three options at this point. They can choose to sign and pass the bill, in which case it becomes a law. They can also refuse to sign or veto the bill, sending it back to the House of Representatives with their reasons for the veto. If the House and Senate still believe the bill should become a law, they can hold another vote, and if two-thirds of the Representatives and Senators support the bill, the President's veto is overridden and the bill becomes a law. The President's third option is to do nothing, which is called a "pocket veto". If Congress is in session, the bill automatically becomes law after 10 days of inaction by the President. However, if Congress is not in session, the bill does not become a law.

Understanding the Emotional Journey of Lawmaking

You may want to see also

Conference committees

If the Conference Committee reaches a compromise, it prepares a written conference report, which is submitted to each chamber. The conference report must be approved by both the House and the Senate.

The Complex Journey of a Bill to Law

You may want to see also

Presidential action

Once a bill has been passed by both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, it is then sent to the President for review. The President has the power to take one of three actions:

Sign and pass the bill

If the President approves of the bill, they can sign it, and it becomes a law.

Veto the bill

If the President does not approve of the bill, they can veto it, which means refusing to sign it. The bill is then sent back to Congress, along with the President's reasons for the veto. Congress can then attempt to override the veto by holding another vote on the bill. If two-thirds of the Representatives and Senators support the bill, the President's veto is overridden, and the bill becomes a law. A successful override of a presidential veto is rare.

Do nothing (pocket veto)

If the President does not sign or veto the bill within ten days (excluding Sundays) and Congress is not in session, the bill does not become a law. This is called a "pocket veto" and cannot be overridden by Congress. However, if Congress is in session, the bill automatically becomes law after ten days, even without the President's signature.

Once a bill has been passed by both chambers of Congress and approved by the President, or if a presidential veto has been overridden, the bill becomes a law. It is then enforced by the government and included in the next edition of the United States Statutes at Large.

Understanding the Medical Law-Making Process

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A bill is a proposal for a new law or a change to an existing law.

The idea for a bill can come from a sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives, be proposed during their election campaign, or be petitioned by citizens or citizen groups.

Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned a number and a sponsor. It is then sent to a committee that will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill.

After being introduced and assigned to a committee, a bill must be approved by the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, and the President. If the President does not approve, Congress can still override the veto for the bill to become a law.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was proposed by President John F. Kennedy and later passed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The bill was first introduced by Kennedy in 1963, but due to his assassination, it was left to Johnson to sign the bill into law on July 2, 1964.