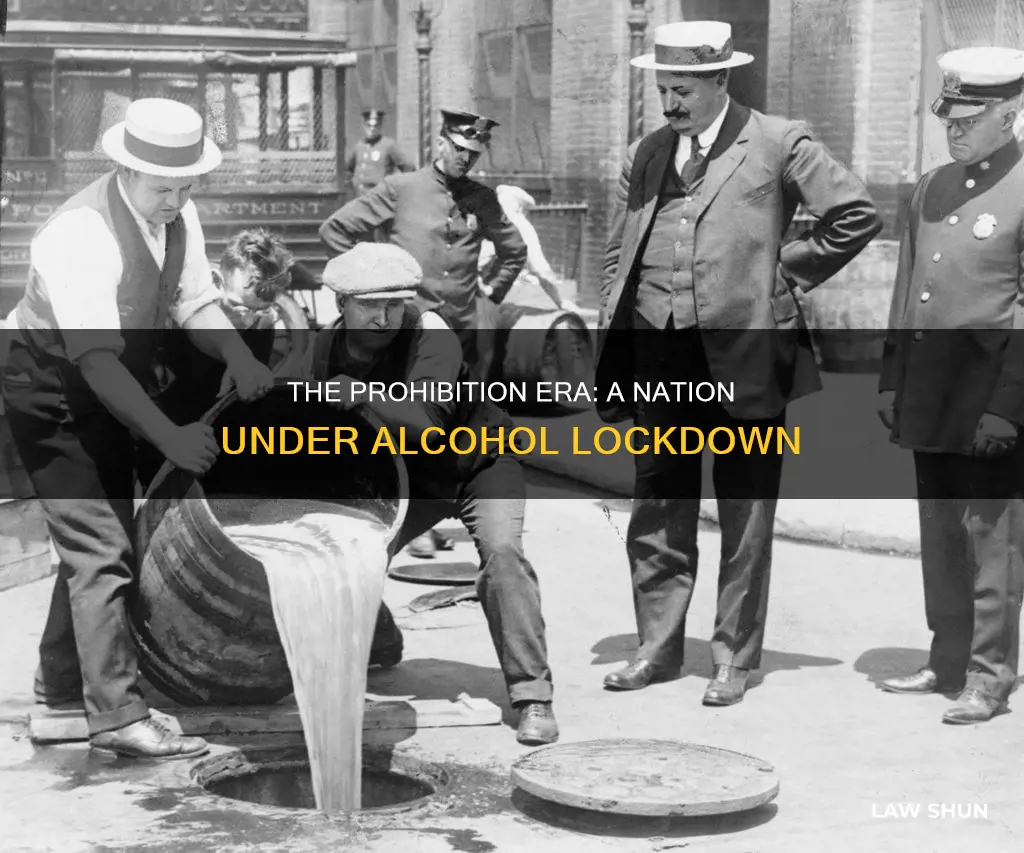

The Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquors in the United States, was ratified on January 16, 1919, and came into effect on January 17, 1920, marking the start of the Prohibition era.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year national prohibition became a law | 1920 |

| Amendment | 18th Amendment |

| Year the 18th Amendment was ratified | 1919 |

| Year the 21st Amendment was ratified | 1933 |

What You'll Learn

The Eighteenth Amendment

By the late 1920s, opposition to Prohibition grew, with critics arguing that it lowered tax revenue and imposed "rural" Protestant religious values on "urban" America. The amendment was eventually repealed on December 5, 1933, with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment, which marked the end of the Prohibition era.

The Legislative Process: How a Bill Becomes Law

You may want to see also

The Volstead Act

The enactment of the Volstead Act had a significant impact on society and the economy. It led to the closure of distilleries, breweries, and liquor stores, and the emergence of black markets and criminal syndicates dedicated to distributing alcohol. The production, importation, and distribution of alcoholic beverages, once legitimate businesses, fell into the hands of criminal gangs, who often engaged in violent confrontations to control the market.

By the late 1920s, opposition to the Volstead Act and Prohibition grew, with critics arguing that it lowered tax revenues and imposed "rural" religious values on "urban" areas. The act also faced waning support due to the challenges of enforcement and the unintended consequences, including the proliferation of illegal drinking establishments known as "speakeasies" and the rise in gang violence and organised crime.

In 1933, Congress passed the Cullen-Harrison Act, which legalised low-alcohol beer and wine, signalling the beginning of the end for Prohibition. The 21st Amendment, ratified on December 5, 1933, ultimately repealed the 18th Amendment, rendering the Volstead Act void and restoring control of alcohol regulation to the states.

When Did ADA Become Law?

You may want to see also

The Twenty-First Amendment

The Prohibition era was marked by the illegal production and sale of liquor ("bootlegging"), the emergence of illegal drinking spots ("speakeasies"), and the rise of gang violence and organised crime. Despite early successes, including a decline in arrests for drunkenness and a reported 30% drop in alcohol consumption, those who wanted to keep drinking found increasingly inventive ways to do so. Bootleggers smuggled alcohol into the country or distilled their own, speakeasies proliferated, and organised crime syndicates formed to coordinate the complex chain of operations in the black-market alcohol industry.

The negative consequences of Prohibition included the loss of tax revenue from alcohol sales, the negative impact on the economy by eliminating jobs in the alcohol industry, and the rise of criminal gangs and widespread corruption as law enforcement officials were bribed. By the end of the 1920s, support for Prohibition was waning, and in the midst of the Great Depression, the need to create jobs and revenue by legalising the liquor industry became more pressing. Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for president on a platform calling for the repeal of Prohibition and won the 1932 election.

SNL's "How a Bill Does Not Become a Law" Explained

You may want to see also

The Anti-Saloon League

The League drew most of its support from Protestant evangelical churches, and lobbied at all levels of government for legislation to prohibit the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages. It concentrated on legislation and how legislators voted, rather than whether they drank or not. It was strongest in the South and rural North, and its supporters included Protestant ministers and their congregations, especially Methodists, Baptists, Disciples of Christ and Congregationalists.

The League's founder and first leader, Howard Hyde Russell, believed that leadership should be selected, not elected. He built the organisation from the bottom up, shaping local leagues and promoting the most promising young men to leadership positions at the local and state levels. This strategy reinvigorated the temperance movement.

The League used emotion-based tactics in its campaigning, appealing to patriotism, efficiency and anti-German sentiment during World War I. Its activists saw themselves as preachers fulfilling their religious duty of eliminating liquor in America.

The League was also the first to use many modern techniques of public relations to mobilise public opinion in favour of a dry, saloonless nation. It published thousands of fliers, pamphlets, songs, stories, cartoons, dramas, magazines and newspapers. It also used pressure politics in legislative politics, which it is credited with developing.

The League's most prominent leader was Wayne Wheeler, although Ernest Cherrington and William E. "Pussyfoot" Johnson were also highly influential. Wheeler's deep resentment for alcohol stemmed from an incident in his youth when he was injured by a drunk worker on a farm. Wheeler later developed a policy known as 'Wheelerism', where he used the media to make it seem as though the general public supported a particular issue. Wheeler became known as the "dry boss" due to his influence and power.

The League's triumph was the passage of the Eighteenth (Prohibition) Amendment in 1919, which amended the Constitution to prohibit the manufacture, transportation and sale of intoxicating liquors. However, the League ceased to be a force in American politics after the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1933. It merged with other groups in 1950 to form the National Temperance League, and in 2016 became the American Council on Addiction and Alcohol Problems, which continues to lobby to restrict alcohol advertising and promote temperance.

Business Law Attorney: Steps to Take for a Career

You may want to see also

Speakeasies

The quality of alcohol sold in speakeasies varied, with some establishments watering down good whiskey and gin to sell larger quantities, while others resorted to selling moonshine or industrial alcohol, which could be poisonous. To hide the taste of poor-quality liquor, speakeasies offered mixed drinks or "cocktails", combining alcohol with ginger ale, Coca-Cola, sugar, mint, lemon, fruit juices, and other flavourings.

Organised criminals, such as Al Capone, seized the opportunity to exploit the lucrative criminal racket of speakeasies, and organised crime in America exploded because of bootlegging. Speakeasies were so profitable that they continued to flourish despite raids and arrests by police and agents of the Bureau of Prohibition. By the late 1920s, there were anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000 speakeasy clubs in New York City alone.

With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, speakeasies largely disappeared, making way for licensed barrooms, far lower in number, where liquor was subject to federal regulation and taxes.

Ideas to Federal Laws: The Complete Process

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

1920.

The Volstead Act.

The Eighteenth Amendment.

1933.