Desegregation in the United States has been a long and arduous process, with racial segregation being enforced across the nation for much of its history. The practice, which systematically separated people based on racial categorisations, was legally and socially mandated, particularly in the American South.

The journey towards desegregation gained momentum during the Civil Rights Movement, with a focus on ending segregation in schools and the military. This process began with President Harry Truman's 1948 executive order to integrate the armed forces, and the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, which ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Despite these advances, de facto segregation remains prevalent in contemporary America, and the fight for racial equality continues.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Date of desegregation becoming law in the USA | 1948 |

| Who was responsible for the law | President Harry Truman |

| What was the name of the law | Executive Order 9981 |

| What did the law do | Ordered the integration of the armed forces |

| What was the impact of the law | A major advance in civil rights |

What You'll Learn

Desegregation in the military

During the American Civil War, more than 180,000 Black people served with the Union Army and Navy in segregated units, known as the United States Colored Troops, under the command of White officers. During World War I, Black officers were severely underrepresented, and during World War II, most officers were White, and the majority of Black troops served as truck drivers and stevedores.

In 1947, civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, formed the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service and Training, which was later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation. The following year, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which abolished discrimination "on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin" in the United States Armed Forces. This order led to the reintegration of the services during the Korean War (1950–1953). It was a crucial event in the post-World War II civil rights movement and a major achievement of Truman's presidency.

Truman's order was inspired in part by an attack on Isaac Woodard, an African American World War II veteran, who was beaten and blinded by police in South Carolina in 1946, just hours after being honorably discharged from the Army and while still in uniform. The attack caused national outrage and helped inspire Truman's move to desegregate the military. Truman also established the President's Committee on Civil Rights, whose report, "To Secure These Rights," condemned all forms of segregation and called for an immediate end to discrimination and segregation in all branches of the armed services.

Despite Truman's order, the US military remained largely segregated, and it was not until the Korean War that significant progress was made toward desegregation. The US Army had accomplished little desegregation during peacetime, and when the war broke out, the segregated Eighth Army was sent to defend South Korea. Most Black soldiers served in segregated support units in the rear, while others served in segregated combat units, such as the 24th Infantry Regiment. However, the first months of the war were disastrous for US forces, and commanders began accepting Black replacements for White units, thus integrating their units. The practice occurred throughout the Korean battle lines and proved that integrated combat units could function effectively. On July 26, 1951, exactly three years after Truman's executive order, the US Army formally announced its plans to desegregate.

The last of the all-Black units in the US military was abolished in September 1954, and in 1963, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara issued a directive encouraging military commanders to use their financial resources to combat discrimination in facilities used by soldiers and their families. While Truman's executive order was a crucial step toward ending segregation in the military, it would take many more years of effort and struggle to fully achieve desegregation in the US Armed Forces.

The Evolution of Laws: History's Impact

You may want to see also

Desegregation in schools

One of the earliest attempts to desegregate schools occurred in Iowa in 1868, when the Iowa Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional in Clark v. Board of School Directors. However, this decision had little impact beyond the state, and racial segregation in schools remained prevalent.

The turning point in the fight for desegregation came with the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case in 1954. The case was originally filed in Topeka, Kansas, after seven-year-old Linda Brown was rejected from an all-white school. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, declaring that separate schools were "inherently unequal". This decision marked the beginning of the end for state-sponsored segregation.

Despite the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the implementation of desegregation faced significant opposition and delays. In the South, some states resisted integration, and it took years for them to comply with the court's decision. In the North, while there was less overt resistance, de facto segregation persisted due to the flight of white families to suburban areas and the establishment of "segregation academies".

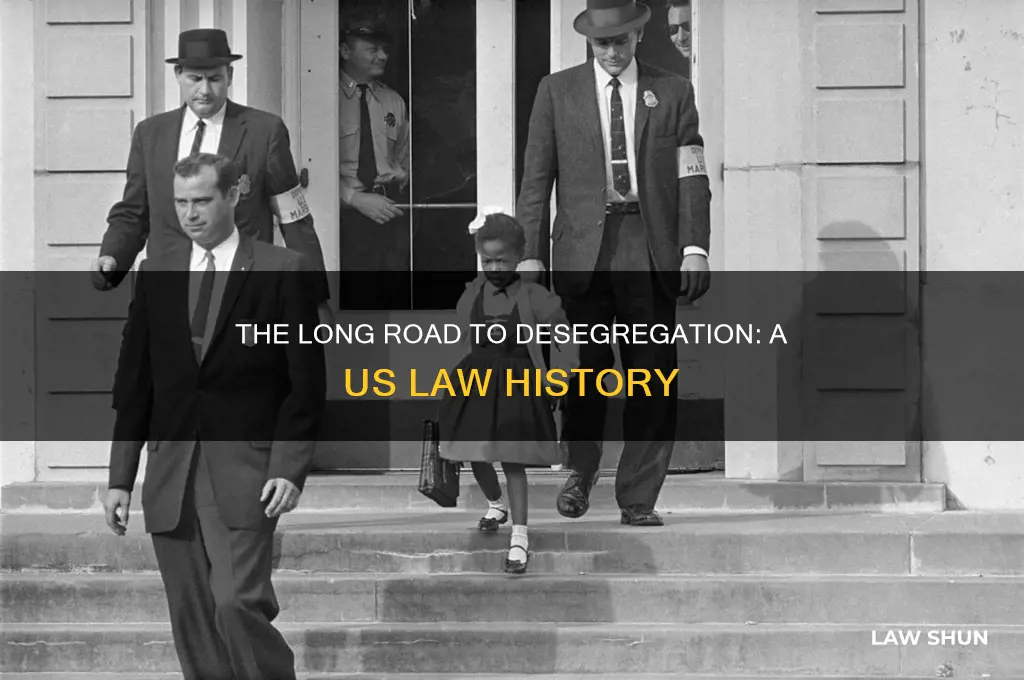

The process of desegregating schools was not without its challenges and growing pains. In 1957, nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas, sparking the Little Rock Crisis. The students were initially prevented from entering the school by the National Guard, but with the intervention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, they were eventually able to attend. This incident highlighted the tension and resistance surrounding school desegregation.

While progress was made in the decades following the Brown v. Board of Education decision, school segregation remains an issue in contemporary education. Studies have shown that segregation has increased since the 1990s, and the achievement gap between white and black students persists. Additionally, structural racism continues to play a role, with predominantly white trustees operating in many school boards even after desegregation.

Overall, the fight for desegregation in schools has been a lengthy and ongoing battle in the United States. While there have been significant milestones and advancements, the work towards achieving true equality in education is far from over.

Becoming a Law Teacher: Australia's Requirements and Pathways

You may want to see also

Housing segregation

History of Housing Segregation

The practice of housing segregation in the US can be traced back to the 19th and 20th centuries, when it was legally mandated, often under the guise of separate but equal. The first steps towards official segregation came in the form of "Black Codes," laws passed throughout the South around 1865 that dictated most aspects of Black people's lives, including where they could live and work. These codes ensured the availability of Black people as a source of cheap labour after the abolition of slavery.

Jim Crow Laws

Segregation became further entrenched through a series of Jim Crow laws, which enforced the separation of Black and white people in various spheres, including residential areas. During this time, some cities also instituted zoning laws that prohibited Black families from moving into white-dominant neighbourhoods. While the Supreme Court ruled against such zoning practices in 1917, finding them unconstitutional due to their interference with property rights, alternative methods were soon developed to maintain segregation.

Racially Restrictive Covenants

One such method was the use of racially restrictive covenants, which legally prohibited African Americans from owning or occupying homes in designated communities. These covenants provided a legal framework for systematic segregation until the late 1940s. Even after the Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable in 1948, they continued to be used as powerful social signals to exclude people of colour from certain neighbourhoods.

Redlining and Federal Policies

In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure mortgages in African American neighbourhoods, contributing to the concentration of poverty and disinvestment in these areas. This practice, known as redlining, was further exacerbated by federal transportation investments that facilitated automobile access for white suburban residents while cutting off access to economic opportunities for Black communities.

Fair Housing Act

It wasn't until the 1960s and 1970s that federal and local governments began to actively address housing discrimination. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited racial discrimination in the renting, selling, and financing of housing. However, explicit discrimination was often replaced by more subtle and ostensibly race-neutral methods of excluding people of colour from white neighbourhoods.

Persistence of Segregation

Despite legal and legislative changes, the legacy of housing segregation persists in the US. Gentrification, exclusionary zoning policies, and ongoing discrimination in housing and lending markets continue to create and reinforce segregated neighbourhoods. Additionally, the lack of consistent enforcement of fair housing laws has hindered progress towards racial integration.

The Journey of a Bill to Law Explained

You may want to see also

Racial discrimination in employment

Desegregation in the United States was a long and arduous process that began in the 17th century and continued until the 1960s. The focus of desegregation efforts shifted over time, from the military to schools, housing, and employment.

Historical Context

The history of racial discrimination in employment in the United States is deeply rooted in the country's past. Even after the abolition of slavery, Black Americans continued to face marginalization and restricted access to various opportunities, including employment.

Legislation and Policies

Various laws and policies have been enacted to address racial discrimination in employment. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), prohibits discrimination based on race or color in any aspect of employment, including hiring, firing, pay, promotions, and job assignments. Despite this legislation, racial discrimination in employment remains prevalent.

Impact on Employment Outcomes

Research has revealed significant disparities in employment outcomes between Black and White individuals. Black individuals are twice as likely to be unemployed and earn nearly 25% less when they are employed. This indicates that racial discrimination in hiring and promotion practices continues to exist, perpetuating these inequalities.

Discrimination in Hiring

A study conducted by Mullainathan and Bertrand (2004) provides compelling evidence of racial discrimination in the hiring process. By sending out identical résumés with either Black-sounding or White-sounding names, they found that résumés with White-sounding names received 50% more callbacks, suggesting that race plays a significant role in employers' decisions.

Discrimination in Promotion and Pay

In addition to hiring, racial discrimination also occurs in promotion and pay practices. Despite policies mandating equal employment opportunities, Black individuals continue to be underrepresented in managerial and leadership positions. This indicates that racial biases influence not only hiring decisions but also promotion opportunities within organizations.

Addressing Racial Discrimination in Employment

To address racial discrimination in employment, the EEOC works through its 53 offices nationwide to stop and remedy racial barriers in employment. This includes resolving charges of employment discrimination, recovering monetary compensation for victims, and implementing changes to employer policies to prevent future discrimination.

Despite these efforts, racial discrimination in employment remains a complex and pervasive issue. Addressing it requires a multifaceted approach, including continued enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, increased awareness and education, and the promotion of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in organizations.

Finalizing Divorce: The Legal Timeline Explained

You may want to see also

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

In June 1963, President John Kennedy asked Congress for a comprehensive civil rights bill, induced by massive resistance to desegregation and the murder of Medgar Evers. After Kennedy's assassination in November, President Lyndon Johnson pressed hard, with the support of Roy Wilkins and Clarence Mitchell, to secure the bill's passage the following year.

The Act was not passed without difficulty. Opposition in the House of Representatives stalled the bill in the House Rules Committee. In the Senate, Southern Democratic opponents attempted to talk the bill to death in a filibuster. However, House supporters overcame the Rules Committee obstacle by threatening to send the bill to the floor without committee approval. The Senate filibuster was overcome through the floor leadership of Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, the support of President Lyndon Johnson, and the efforts of Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois, who convinced enough Republicans to support the bill over Democratic opposition.

How Resolutions Become Laws: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, General Dwight D. Eisenhower allowed African American soldiers to join White military units in combat for the first time.

Desegregation was made law in the USA through the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Lowell High School in Massachusetts has accepted students of all races since its founding. The earliest known African American student, Caroline Van Vronker, attended the school in 1843.

In 1868, Iowa became the first state in the USA to desegregate schools by court order in Clark v. Board of School Directors.