Martial law is a legal term for when military authorities take control of civil governance and law enforcement. It occurs when the military assumes temporary control over various civilian authorities. The Constitution does not define or specify who can declare it, and there is no federal law that explicitly authorizes the president to declare martial law. While several presidents have declared martial law throughout history, the Supreme Court has never explicitly held that the president can. Therefore, it is unclear whether the president can legally declare martial law independently.

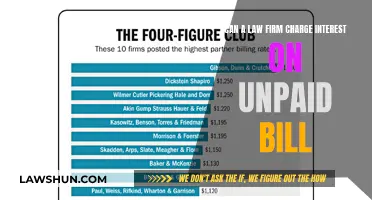

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can a US president declare martial law on his own? | It is unclear. The US Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it specify who can declare it. |

| Has a US president ever declared martial law? | Yes. Examples include Franklin D. Roosevelt's internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II and Abraham Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War. |

| What is martial law? | Martial law occurs when the military assumes temporary control over various civilian authorities. |

| What happens during martial law? | All civilian laws are suspended, and military leaders may create and enforce their own laws, detain people, and take over local governments. |

| What is the Posse Comitatus Act? | Passed by Congress in 1878, this act prevents the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities without congressional approval. |

| What is the Insurrection Act? | Passed in 1807, this act allows the president to deploy military forces to put down rebellions and help local law enforcement deal with domestic violence. |

| Can martial law be declared in the US today? | It is rare but not impossible. It is typically a last resort due to the potential for abuse of power. |

What You'll Learn

The US Constitution and martial law

The US Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it specify who can declare it. However, it is generally understood as a temporary transfer of authority from civilian to military control. This can occur at the local, state, or national level.

The US Constitution does not give the President "conclusive and preclusive" authority over the domestic use of the military. Instead, it vests power in the legislative branch, meaning the President cannot act against Congress's wishes in this area. The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 further limits the President's power by preventing the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities without congressional approval.

The US Constitution does allow for a permitted range of honest judgment in maintaining peace and suppressing violence, but this does not equate to a unilateral declaration of martial law by the President. The Guarantee Clause, for example, requires the federal government to protect states against invasion and domestic violence, but only upon the application of the state legislature or executive.

While the President's declaration of martial law would likely violate the Posse Comitatus Act, some scholars believe the President has the executive power to declare it. This is based on the understanding that the US Constitution does not expressly prohibit it, and that the President has certain emergency powers. However, this scenario is hypothetical, and the likely legal outcome is uncertain.

Throughout history, several US Presidents have declared or approved declarations of martial law, such as President Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus in 1861, and President James Buchanan's actions in Utah in 1857. However, these actions have been limited to specific areas and have often been done with congressional authorization.

Barack Obama's Legal Career: A Retrospective Analysis

You may want to see also

Historical instances of martial law in the US

Martial law in the United States refers to instances in history where a region, state, city, or the entire country was placed under the control of a military body. While there is no universal definition of the term, it often refers to the use of the military for law enforcement, where the military officer in command can rule by decree and detain anyone for any reason.

Boston (1774)

The British Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts, including the Massachusetts Government Act, which placed Boston under martial law by closing its port and restricting town meetings. This was in response to the Boston Tea Party and was enforced by General Thomas Gage, who was appointed military governor.

Virginia (1775)

Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation declaring martial law and offering freedom to indentured servants and enslaved individuals who joined British forces against the rebelling colonists. This move aimed to disrupt the colonial rebellion by encouraging enslaved people to support the British.

New Orleans (1814-1815)

During the War of 1812, Gen. Andrew Jackson declared martial law in New Orleans, Louisiana, which lasted for three months.

Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri (1863)

On September 15, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln imposed Congressionally authorized martial law on these three states during the Civil War. Lincoln had previously suspended habeas corpus under his own authority in 1861, allowing him to arrest one-third of the Maryland state assembly.

Chicago (1871)

After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Chicago mayor Roswell B. Mason declared martial law and placed General Philip Sheridan in charge of the city.

Vigo County, Indiana (1935-1936)

In response to the General Strike of 1935, Gov. Paul V. McNutt declared martial law in Vigo County, Indiana, which lasted for about six months.

Oklahoma Oil Fields (1932)

Gov. William "Alfalfa Bill" Murray declared martial law in the Oklahoma oil fields during a nonviolent dispute between the state government and oil producers over production limits.

Utah Territory (1857-1858)

Gov. Brigham Young declared martial law in the Utah Territory to facilitate armed resistance to approaching federal troops sent by President James Buchanan to enforce federal law.

Hawaii (1941)

During World War II, local military officials in Hawaii declared martial law, which was later approved and expanded by Franklin D. Roosevelt's executive order to include the incarceration of Japanese-Americans on the West Coast.

Congress' Power to Repeal Laws: Understanding Legislative Authority

You may want to see also

The Insurrection Act

In 2025, the Trump administration considered invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807 to address concerns about the US southern border. Critics worried that invoking the Act would consolidate federal power and give Trump more leeway to use the military for domestic law enforcement or immigration enforcement.

Arizona's State Law: Can Arpaio Be Convicted?

You may want to see also

The Posse Comitatus Act

The Act's title is derived from the legal concept of posse comitatus, which refers to the authority of a county sheriff or law officer to conscript individuals to assist in maintaining peace. The Posse Comitatus Act specifically prevents the United States military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities without congressional approval. This separation between the military and civilian law enforcement is rooted in the belief that military interference in civilian affairs poses a threat to democracy and personal liberty.

The original Posse Comitatus Act applied only to the United States Army, but amendments over the years have expanded its scope. In 1956, the Act was updated to include the Air Force, and in 2021, the National Defense Authorization Act further broadened it to cover the Navy, Marine Corps, and Space Force. The Coast Guard, despite being a part of the armed services, is not included in the Act as it has explicit law enforcement authority.

California's Law Enforcement and Automatic Knives: What's Allowed?

You may want to see also

Martial law and civil liberties

The concept of martial law and the authority to declare it is not well understood. The US Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it specify who can declare it. However, it is generally understood that martial law refers to instances when a nation's armed forces assume the governance of an area, temporarily replacing civilian authority with military rule. This typically occurs in cases of conflict, occupation, or emergency, where civilian government is absent or has stopped functioning.

In the United States, the President's ability to declare martial law is a subject of debate. While some scholars argue that the President has the executive power to do so, others contend that congressional authorization is required. The Constitution does not explicitly grant the President the authority to declare martial law, and the Supreme Court has never specifically held that the President can. However, several Presidents throughout history have imposed or approved declarations of martial law. For example, President Lincoln imposed Congressionally authorized martial law on Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri during the Civil War, suspending habeas corpus and civil rights. The Supreme Court later ruled that such an imposition of martial law was unconstitutional in areas where local courts were still in session.

The Posse Comitatus Act, passed by Congress in 1878, further complicates the issue. The act forbids the US military from participating in civilian law enforcement activities without congressional approval, strengthening the separation of powers between Congress and the President. Additionally, the Insurrection Act of 1807 allows the President to deploy military forces to address rebellions and assist local law enforcement, but it does not explicitly grant the power to declare martial law.

Ultimately, it is unclear whether the President can unilaterally declare martial law. Congress might be able to authorize a presidential declaration, but this remains undecided. State officials, such as governors, have the power to declare martial law within their states, but their actions must abide by the US Constitution and are subject to federal court review.

The imposition of martial law has significant implications for civil liberties. When martial law is declared, civilian authorities are replaced by the military, resulting in the suspension of civil law, civil rights, and habeas corpus. Policy decisions are made by military officers, and accused individuals are tried by military tribunals rather than civilian courts. Martial law effectively removes the usual checks and balances on government power, potentially leading to abuses of authority and violations of constitutional rights, as seen in the Illinois Mormon War and the Utah War.

Law Funding Cybersecurity Education for Children: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The U.S. Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it specify who can declare it. While some scholars believe the president has the executive power to declare martial law, others argue that the president needs congressional authorization to impose it in a civilian area. Therefore, it is unclear whether a president can declare martial law on their own.

Martial law refers to instances when a nation's armed forces assume the governance of an area, temporarily replacing civil authority with military rule. It is typically declared in times of extreme emergency, when civilian government and law enforcement have ceased to function or become ineffective.

Yes, martial law has been imposed at least 68 times in limited, usually local areas of the United States. Notable instances include New Orleans during the Battle of New Orleans, Hawaii after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri during the Civil War.

Yes, Congress has the power to impose martial law, and they have done so on several occasions. For example, in 1861, Congress authorized President Lincoln to impose martial law in Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri.