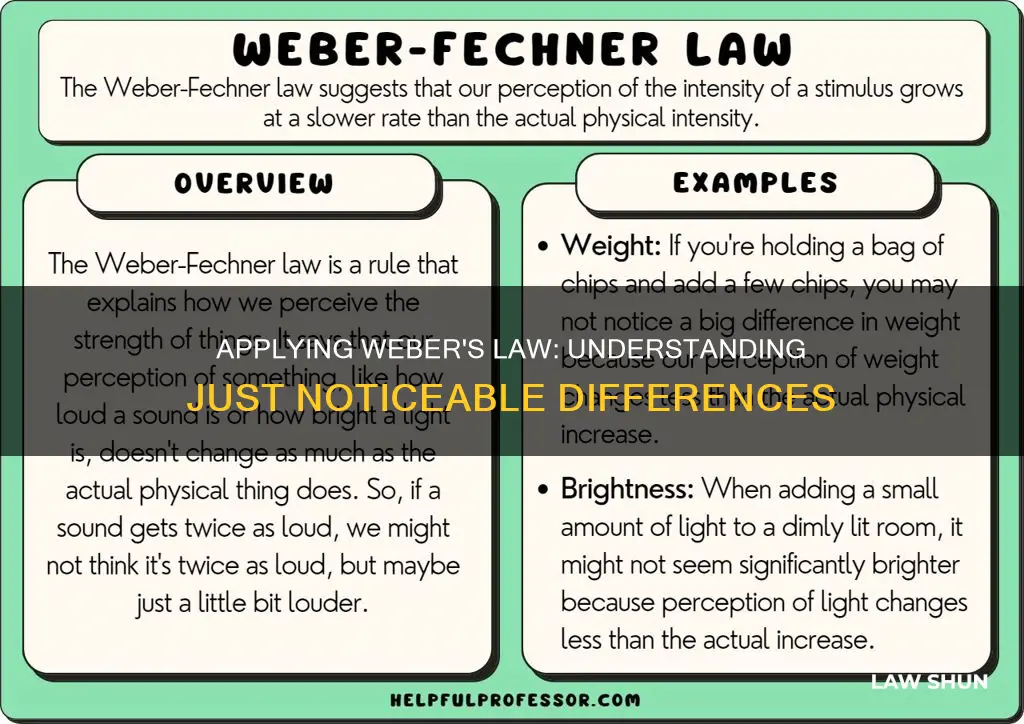

Weber's Law of Just Noticeable Differences, observed by 19th-century experimental psychologist Ernst Weber, states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus. In other words, the size of the just noticeable difference is proportional to the original stimulus value. Weber's Law can be applied to a variety of sensory modalities, including brightness, loudness, mass, and line length.

Weber's Law has been used in various fields of research, including human time perception, psychophysics, and consumer behaviour. For example, in time perception, Weber's Law predicts a linear relationship between sensitivity and duration on interval timing tasks. In psychophysics, Weber's Law relates to the relation between the actual change in a physical stimulus and the perceived change, including stimuli to all senses: vision, hearing, taste, touch, and smell. In consumer behaviour, Weber's Law has been used to explain why consumers might neglect to shop around to save a small percentage on a large purchase but will shop around to save a large percentage on a small purchase.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Weber's Law of Just Noticeable Differences |

| Discovery | Discovered by Ernst Heinrich Weber in 1834 |

| Field | Psychophysics |

| Scope | All senses: vision, hearing, taste, touch, and smell |

| Formula | dS=K.S |

| Scope of Application | Brightness, loudness, mass, line length, etc. |

| Limitations | Does not hold for low or high intensities |

What You'll Learn

Weber's Law and the perception of weight

Weber's Law, also known as the Weber-Fechner Law, is a psychological principle that relates to human perception. It was formulated by Gustav Theodor Fechner, a student of the German physiologist and psychologist Ernst Heinrich Weber, in 1860. The law states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus. In other words, the minimum increase in stimulus that will produce a perceptible increase in sensation is proportional to the pre-existent stimulus.

Weber's Law can be applied to various sensory modalities, including weight perception. For example, if a weight of 105 grams can be distinguished from 100 grams, the just-noticeable difference (JND) or differential threshold is 5 grams. If the mass is doubled, the differential threshold also doubles to 10 grams, so that 210 grams can be distinguished from 200 grams. In this case, the weight must increase by 5% for someone to be able to detect the increase reliably, and this minimum required fractional increase (of 5% of the original weight) is referred to as the "Weber fraction".

Weber's Law has been found to hold good for weight perception, with the ratio of intensity remaining constant for several weights. This was demonstrated by Weber, who conducted research on the perceived difference in weight.

Understanding Lemon Law Applicability for Private Owners

You may want to see also

Weber's Law and the perception of brightness

Weber's Law, discovered by 19th-century experimental psychologist Ernst Heinrich Weber, is a psychological law that quantifies the perception of change in a given stimulus. The law states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus. In other words, the size of the just noticeable difference (JND) is a constant proportion of the original stimulus value.

Weber's Law can be applied to various sensory modalities, including brightness. In the context of brightness, Weber's Law predicts that the change in brightness that will be just noticeable to an observer is a constant ratio of the original brightness. For example, if you present two spots of light, each with an intensity of 100 units, and then gradually increase the intensity of one of the spots, the point at which the observer notices a difference in brightness will be the JND. This difference threshold can be calculated using Weber's Law, and it will be constant for a given observer, regardless of the initial brightness.

Weber's Law has been found to hold true for brightness perception within a wide middle range of intensities. However, it fails at very low light levels and may break down at twilight levels. At very low light levels, human vision relies on the observer's own neural noise, and Weber's Law does not apply.

Weber's Law has been applied in various fields beyond human senses, including numerical cognition, public finance, and pharmacy. It provides a framework for understanding how small changes in stimulus intensity can result in noticeable differences in sensory experience.

Good Samaritan Laws: Non-Callers and Legal Protection

You may want to see also

Weber's Law and the perception of loudness

Weber's Law of Just Noticeable Difference, discovered by 19th-century experimental psychologist Ernst Weber, states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus. In other words, the size of the just noticeable difference is a constant proportion of the original stimulus value.

Weber's Law can be applied to various sensory modalities, including loudness. For example, if a spot of light with an intensity of 100 units is increased to 110 units, the observer's difference threshold would be 10 units. This can be used to predict the size of the observer's difference threshold for a light spot of any other intensity value.

Weber's Law does not quite hold for loudness. It is a fair approximation for higher intensities, but not for lower amplitudes. Weber's Law fails at perception of higher intensities, as intensity discrimination improves at higher volumes.

Weber's Law has been applied in other fields of research beyond the human senses, such as in psychological studies, which show that it becomes increasingly difficult to discriminate between two numbers as the difference between them decreases.

Left Lane Laws: City Street Exception?

You may want to see also

Weber's Law and the perception of time

Weber's Law of Just Noticeable Differences, postulated by 19th-century experimental psychologist Ernst Weber, states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus. In other words, the size of the just noticeable difference is a constant proportion of the original stimulus value. Weber's Law can be applied to a variety of sensory modalities, including brightness, loudness, mass, and line length.

Weber's Law can also be applied to the perception of time. As per Weber's Law, the more years a person has experienced, the more quickly additional years seem to pass. This is because the sensitivity to time increases proportionally with increases in stimulus intensity. However, there is conflicting evidence on the relationship between temporal sensitivity and duration. While Weber's Law predicts a linear relationship between sensitivity and duration, other models predict a reverse J-shaped or U-shaped relationship.

In addition, Weber's Law does not always hold true for the perception of time. It has been found to be violated at very short intervals, with sensitivity to changes in duration decreasing from a high value to a horizontal asymptote at a point between 50 and 2,000 ms. This is known as the "near miss" of Weber's Law.

Securities Laws: Private Companies' Obligations and Exemptions

You may want to see also

Weber's Law and the perception of line length

Weber's Law, also known as the Law of Just Noticeable Difference, is a psychological principle that can be applied to various sensory modalities, including line length. The law states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus. In other words, the size of the just noticeable difference is proportional to the original stimulus value.

Weber's Law can be applied to the perception of line length through experiments that involve participants discriminating between the lengths of two lines. For example, an experiment may involve presenting participants with two line segments of different lengths and asking them to choose the longer one. By systematically varying the lengths of the lines and analysing the participants' responses, researchers can determine the difference threshold, which is the minimum amount by which the stimulus intensity must be changed for the difference to be noticeable.

The difference threshold can then be used to calculate the Weber fraction, which is the ratio of the difference threshold to the original stimulus value. If Weber's Law holds true for line length perception, the Weber fraction should remain constant across different line lengths.

One study by Ono (1967) investigated whether Weber's Law applied equally to simultaneous and nonsimultaneous viewing conditions. The results showed that while Weber's Law was followed under the nonsimultaneous viewing condition, it did not hold under the simultaneous viewing condition.

In summary, Weber's Law can be applied to the perception of line length by conducting experiments that manipulate line lengths and analyse participants' ability to discriminate between them. The difference threshold and Weber fraction are key concepts in determining whether line length perception follows Weber's Law.

Energy Conservation Law: Temperature's Role Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Weber's Law states that the change in a stimulus that will be just noticeable is a constant ratio of the original stimulus.

The difference threshold, or "just noticeable difference", is the minimum amount by which stimulus intensity must be changed to produce a noticeable variation in sensory experience.

The Weber fraction is the difference threshold divided by the original stimulus value.

The Weber-Fechner Law is comprised of two related scientific laws in the field of psychophysics: Weber's Law and Fechner's Law. Both laws relate to human perception, specifically the relation between the actual change in a physical stimulus and the perceived change.