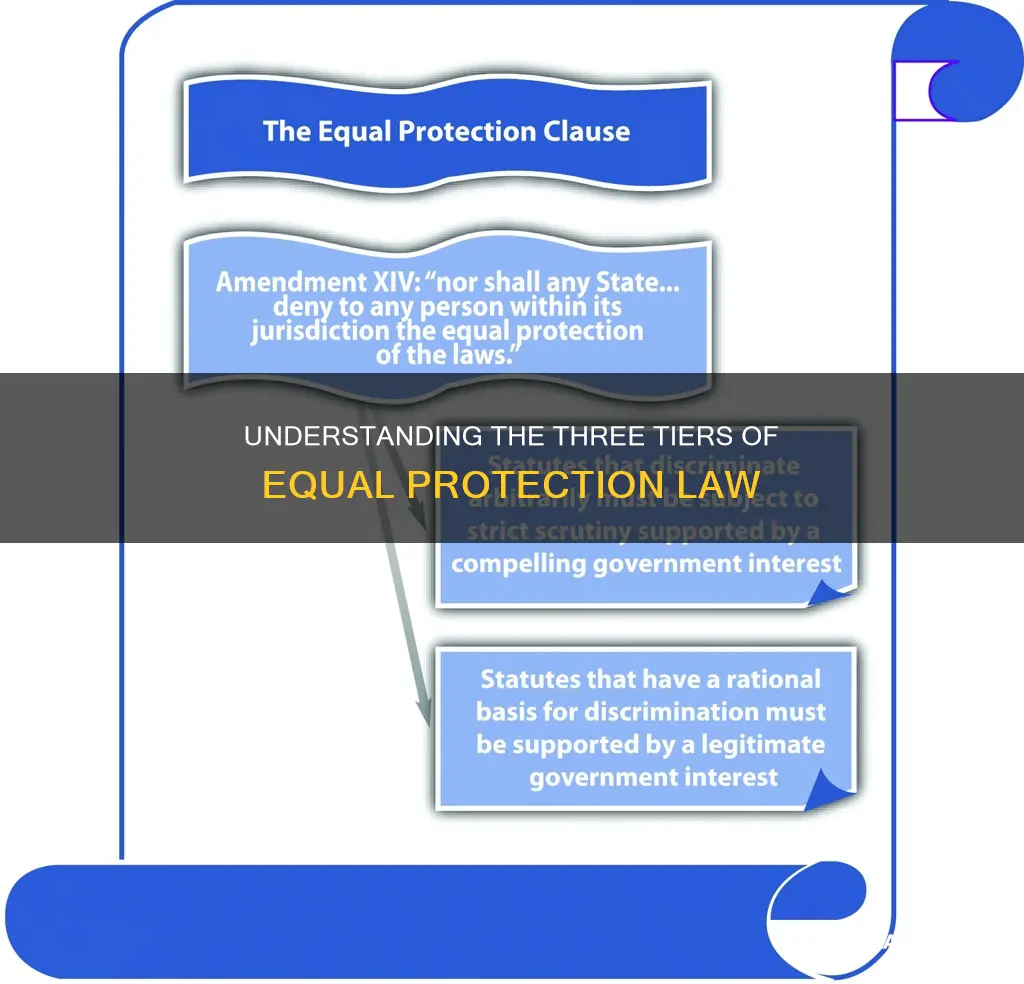

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ensures that no state can deny any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of its laws. Over time, three tiers of scrutiny have been developed for reviewing equal protection challenges: strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, and rational basis review. Strict scrutiny is triggered when a government action involves a suspect classification, such as race, religion, national origin, or lack of citizenship. Intermediate scrutiny is usually triggered by a quasi-suspect classification, such as gender or legitimacy. Rational basis review is the most lenient standard and is applied when no suspect or quasi-suspect classification is involved. These tiers of scrutiny reflect the balance between federal oversight and state autonomy, ensuring that equal protection is upheld while allowing states to make necessary distinctions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| First Tier | Strict Scrutiny |

| Second Tier | Intermediate Scrutiny |

| Third Tier | Rational Basis Scrutiny |

What You'll Learn

Strict scrutiny

The three tiers applied in equal protection law are strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, and rational basis scrutiny.

The burden of proof falls on the state in cases that require strict scrutiny. The law or policy must be justified by a compelling governmental interest, be narrowly tailored to achieve that goal or interest, and be the least restrictive means for achieving that interest. There must not be a less restrictive way to effectively achieve the compelling government interest.

The Supreme Court has consistently found that classifications based on race, national origin, and alienage require strict scrutiny review. The Supreme Court has also applied strict scrutiny to classifications burdening certain fundamental rights. For example, in Skinner v. Oklahoma, the Court considered an Oklahoma law requiring the sterilisation of persons convicted of three or more felonies involving moral turpitude. In Justice Douglas's opinion invalidating the law, we see the origins of the higher-tier analysis that the Court applies to rights of a "fundamental nature" such as marriage and procreation.

The Supreme Court has established standards for determining whether a statute or policy must satisfy strict scrutiny. One ruling suggested that the affected class of people must have experienced a history of discrimination, be definable as a group based on "obvious, immutable, or distinguishing characteristics", or be a minority or "politically powerless".

Moore's Law and Solar Cells: A Relevant Relationship?

You may want to see also

Intermediate scrutiny

To overcome the intermediate scrutiny test, it must be shown that the law or policy being challenged furthers an important government interest by means that are substantially related to that interest. The government must show that the challenged classification serves an important state interest and that the classification is at least substantially related to serving that interest. The government need not prove that the classification is necessary to serve that interest, as is the case with strict scrutiny.

Courts will sometimes refer to intermediate scrutiny by other names, such as "heightened scrutiny" or "rational basis with bite".

The Supreme Court created the intermediate scrutiny test in Craig v. Boren (1976). In Craig, the Court created the intermediate scrutiny test and applied it to a statute that discriminated on the basis of gender. Since then, courts have found that gender is a protected class, and any statute that discriminates on the basis of gender must undergo the intermediate scrutiny test.

In Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan in 1982, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the burden is on the proponent of the discrimination to establish an "exceedingly persuasive justification" for sex-based classification to be valid. As such, the court applied intermediate scrutiny in a way that is closer to strict scrutiny, and in recent decisions, the Court has preferred the term "exacting scrutiny" when referring to the intermediate level of Equal Protection analysis.

In addition to statutes that discriminate based on gender, statutes that discriminate based on illegitimacy (i.e. children born out of wedlock) are also subject to intermediate scrutiny, according to Matthews v. Lucas (1976) and Trimble v. Gordon (1976).

Courts have also held that intermediate scrutiny is the appropriate standard for certain First Amendment issues, such as regulating mass media, adult entertainment, and highway signs.

Guitar Songs and Copyright Law: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Rational basis scrutiny

Under rational basis scrutiny, the challenger must prove that the government action is not rationally related to a legitimate government interest. The government need only show that the challenged classification is rationally related to serving a legitimate state interest. The Supreme Court has applied an extremely lax standard to most legislative classifications. In Federal Communications Commission v Beach (1993), the Court said that economic regulations satisfy the equal protection requirement if "there is any conceivable state of facts that could provide a rational basis for the classification".

Justice Stevens, concurring in the Beach case, objected to the Court's test, arguing that it is "tantamount to no review at all".

In Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York (1949), the Court upheld a New York City ordinance prohibiting advertising on commercial vehicles unless the advertisement concerns the vehicle owner's own business. The ordinance, aimed at reducing distractions to drivers, was underinclusive (it applied to some, but not all, distracting vehicles), but the Court said the classification was rationally related to a legitimate end.

In another case, Kotch v. Bd. of River Port Pilot Commissioners (1947), the Court voted 5-4 to uphold a Louisiana law that effectively prevented anyone but friends and relatives of existing riverboat pilots from becoming a pilot. The Court suggested that Louisiana's system might serve the legitimate purpose of promoting "morale and esprit de corps" on the river.

In U.S. v. Carolene Products Co. (1938), regulatory legislation affecting ordinary commercial transactions was deemed not unconstitutional unless it was of such a character as to preclude the assumption that the law rests on a rational basis within the knowledge and experience of the legislature.

HIPAA Laws and Masks: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Suspect classifications

The use of suspect classifications is reviewed by the courts when governmental action disproportionately impacts a particular group. When a statute discriminates against an individual based on a suspect classification, that statute is typically subject to strict scrutiny or intermediate scrutiny. Strict scrutiny requires the law or policy to satisfy a compelling government interest and be narrowly tailored to meet that interest.

To determine whether an individual or group falls under a suspect classification, courts consider various factors, including inherent or highly visible traits, historical disadvantages, and a lack of effective representation in the political process.

In the United States, the Supreme Court has established the judicial precedent for suspect classifications in cases such as Hirabayashi v. United States and Korematsu v. United States, recognising race, national origin, and religion as suspect classifications. While sexual orientation and gender identity are not considered suspect classifications at the federal level, many states do classify them as such.

The practical result of this legal doctrine is that government-sponsored discrimination based on race, skin colour, ethnicity, religion, or national origin is almost always unconstitutional, unless it meets strict criteria, as seen in the Korematsu v. United States and Grutter v. Bollinger cases.

Castle Doctrine: Does It Apply to Apartments?

You may want to see also

Quasi-suspect classifications

Sex and legitimacy of birth have been held to be quasi-suspect classifications. In 2012, the U.S. District Court for Northern California discussed this type of classification but applied heightened scrutiny without specifically labelling gays and lesbians a suspect or quasi-suspect class in its decision. In Windsor v. United States (2012), the Second Circuit Court of Appeals held sexual orientation to be a quasi-suspect classification, determining that laws classifying people on this basis should be subject to intermediate scrutiny.

Intermediate scrutiny is more likely to oppose a discriminatory law when compared to rational basis review, particularly if a law is based on gender. However, a court will likely uphold a discriminatory law under intermediate scrutiny if the law has an exceedingly persuasive justification and applies to real, fact-based, or biological differences between the sexes.

UK-EU Laws: What's the Deal Now?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The three tiers are strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, and rational basis scrutiny.

Strict scrutiny is the highest tier of scrutiny. It requires the government to prove that its action serves a compelling state interest and is narrowly tailored to achieve that interest. This tier is typically applied to cases involving "suspect classifications" such as race, religion, national origin, or alienage.

Intermediate scrutiny is the middle tier. The government must show that its action furthers an important government interest and is substantially related to that interest. This tier is often applied to cases involving "quasi-suspect classifications" such as gender or legitimacy.

Rational basis scrutiny is the lowest tier. The challenger must prove that the government action is not rationally related to a legitimate government interest. This tier is typically applied when no suspect or quasi-suspect classification is involved, such as in cases of economic regulation.

Strict scrutiny: *Fisher v. University of Texas* (2013), *Grutter v. Bollinger* (2003)

Intermediate scrutiny: *United States v. Virginia* (1996), *Craig v. Boren* (1976)

Rational basis scrutiny: *Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York* (1949), *Kotch v. Bd. of River Port Pilot Commissioners* (1947)

The level of scrutiny applied in a case can significantly impact its outcome. Strict scrutiny is often described as "strict in theory and fatal in fact", as it is very difficult for the government to meet this high standard. Rational basis scrutiny, on the other hand, is extremely lenient and most laws subjected to this tier are upheld.