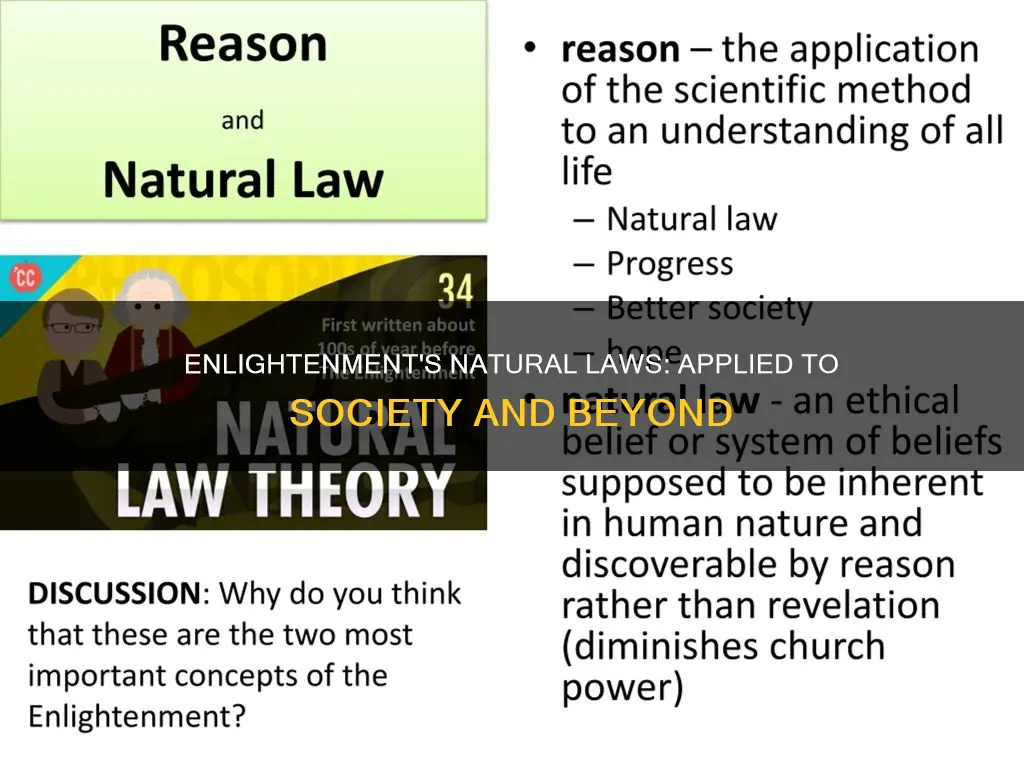

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the divine right of kings and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government or legal rights. This led to classical republicanism, which is built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government.

The idea of natural rights is the concept that a person has certain rights from birth, and because they were not awarded by a particular state or legal authority, they cannot be removed. These rights may include the right to life, liberty, equality, property, justice, and happiness. During the Enlightenment, some of the greatest minds in history set themselves the task of thrashing out what should be considered natural rights.

Natural rights are usually contrasted with the concept of legal rights. Legal rights are those bestowed onto a person by a given legal system (i.e. rights that can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws).

The idea of natural rights is also closely related to that of human rights; some acknowledge no difference between the two, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate the association of human rights with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. This may be because natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dismiss.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Natural rights | Life, liberty, equality, property, justice, happiness, freedom to pursue one's religion, freedom from slavery, right to education, right to work, right to choose one's gender identity |

| Natural law | A philosophy that certain rights or values are inherent by virtue of human nature and can be universally understood through human reason |

| Legal rights | Rights bestowed onto a person by a given legal system |

What You'll Learn

To challenge the divine right of kings

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural law was used to challenge the theory of the divine right of kings. The divine right of kings, or divine-right theory of kingship, is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It asserts that a monarch's right to rule is derived from divine authority and is therefore not subject to the will of the people, the aristocracy, or any other estate of the realm.

The idea of natural law, in contrast, holds that all people have inherent rights conferred by "God, nature, or reason" and not by an act of legislation. This theory was used to challenge the notion that a monarch's right to rule was God-given and thus unchallengeable.

The English philosopher John Locke was a key Enlightenment proponent of natural law. He stressed its role in justifying property rights and the right to revolution. Locke turned Hobbes' prescription around, saying that if the ruler went against natural law and failed to protect "life, liberty, and property," people could justifiably overthrow the existing state and create a new one.

The concept of natural law was also used to challenge the divine right of kings by becoming an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government in the form of classical republicanism. This meant that governments needed the consent of the governed.

The idea of natural law was not new during the Enlightenment, but it took on a new shape during this period, combining inspiration from Roman law, Christian scholastic philosophy, and contemporary concepts such as social contract theory.

California Laws: Are They Applicable in Sslab City?

You may want to see also

To justify the establishment of a social contract

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to justify the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government or legal rights. This led to classical republicanism, which is built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government.

The Enlightenment changed the way people viewed the relationship between the government and citizens, with the idea that people possessed "natural" rights. The Enlightenment thinkers Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau developed ideas about human nature by reflecting on the state and condition of humans before the existence of government and civil society. They agreed that to do so, humans must make a social contract, or an agreement to live together under certain rules for the common good. However, they disagreed on nearly all of the details.

Hobbes, for instance, believed that human nature was essentially corrupt. He thought that people were naturally ruled by their passions, self-interest, and a desire for power. Without laws or government authority, humans threaten each other's rights and lives. In his view, this state of nature was a "war of all against all". Since no one was safe in the state of nature, it was reasonable for humans to form a social contract with each other to create a government. Hobbes's social contract philosophy represents a break from the ancient and medieval belief that humanity was naturally social.

Locke, on the other hand, believed that in a state of nature, humans were rational beings and equal in their natural rights to life, liberty, and property, which could not be taken away by anyone without their consent. People also enjoyed perfect freedom restricted only by the moral code of natural law, a system of justice that applies to all humans, and could not violate one another's rights. He believed that individuals claimed ownership of property when they improved it through their labor. They had a right to that property, and it could not be taken away from them without their consent. Even though humans were generally good, occasional disputes occurred over property rights. Therefore, humans agreed to form a social contract with each other to create a civil government and society to settle these disputes. The purpose of the government was to protect the individual rights of the sovereign people and to promote the common good. The powers of government were therefore limited to these activities, rather than extending to providing goods and services for citizens. In addition, the existence of natural rights is itself a limit on government, as the individual has rights that the government itself must respect.

Rousseau's views were also distinct from those of Hobbes and Locke. He opened his book, *The Social Contract*, with the provocative phrase, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains." Rousseau meant that humans are naturally good and even perfectible in a state of nature. They are innately, or naturally, good, virtuous, equal, and free. He further argued that the institutions of society (family, church, education, government, and civil groups) actually corrupted and enslaved individuals rather than teaching them civic virtues. The creation and ownership of private property created inequalities, and wealth created vanity and corruption. Rousseau believed that society robbed humans of their natural freedom. His view of the social contract and government was based upon this view of human nature and society. He believed that all individuals surrendered their rights and property to the community. Since humans were rational and perfectible beings, they would all agree on good laws. This collective consensus (meaning all agree, rather than just a majority) was called the "General Will" and was the only source of law.

Lemon Laws and Vans: What's the Verdict?

You may want to see also

To justify positive law and government

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to justify positive law and government by challenging the divine right of kings and providing an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government in the form of classical republicanism.

The idea of natural law is based on the belief that certain rights or values are inherent by virtue of human nature and can be universally understood through human reason. During the Enlightenment, thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Rousseau developed social contract theories, which argued that the government's authority lies in the consent of the governed. According to these theories, individuals consented to surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the authority of the ruler in exchange for protection of their remaining rights.

John Locke, for instance, believed that a citizen's liberty must be protected from state interference and that citizens had the right to replace a government that failed them. He also disagreed with Hobbes' view that property was not a natural right, arguing instead that the primary purpose of government is to protect property, along with life and liberty.

The concept of natural law during the Enlightenment also led to the development of classical republicanism, which is built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government. It provided a justification for legal rights and challenged the legitimacy of absolute monarchies.

The Branch's Dilemma: Applying Laws to Facts

You may want to see also

To justify legal rights

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural law was used to justify legal rights by challenging the divine right of kings and providing an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government. This led to classical republicanism, which is built around concepts such as civil society, civic virtue, and mixed government.

The Enlightenment's focus on natural law and natural rights was a reaction to the preceding century of religious conflict in Europe. Enlightenment thinkers sought to curtail the political power of organized religion and prevent another age of intolerant religious war. This led to the development of new ideas, including Deism (belief in God as a Creator who does not intervene in human affairs) and atheism.

One of the key figures of the Enlightenment was John Locke, who is known for his statement that individuals have a right to "Life, Liberty and Property." Locke believed that the natural right to property is derived from labour and that the primary purpose of government is to protect property, including life and liberty, as these are integral to a citizen's existence. He also believed that citizens had the right to replace a government that failed them.

Another influential Enlightenment thinker was Thomas Hobbes, who argued that the essential natural (human) right was "to use his own power, as he will himself, for the preservation of his own Nature; that is to say, of his own Life." Hobbes sharply distinguished this natural "liberty" from natural "laws," which he saw as obligations. He believed that people would not follow the laws of nature without first being subjected to a sovereign power.

The concept of natural law and natural rights was also used by Enlightenment thinkers to challenge the legitimacy of all forms of government and social establishments. For example, Thomas Paine wrote in his "Rights of Man" (1791) that "every civil right grows out of a natural right, which must never be invaded by authorities, whose sole function was to strengthen them."

The idea of natural law and natural rights was also closely related to the development of human rights during the Enlightenment. The 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an important legal instrument that enshrines one conception of natural rights into international soft law.

Understanding ADA Law: Arbitration and Compliance

You may want to see also

To challenge the legitimacy of all establishments

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the legitimacy of all establishments, including the divine right of kings. This became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government or legal rights, which led to classical republicanism.

The idea of natural rights and laws was of particular interest to Enlightenment philosophers, who were primarily concerned with the question of what system of government is best. The debate around natural rights was secondary to this discussion but was relevant to it since philosophers were obliged to consider the success of a particular political system by how well it protected citizen rights. Some thinkers suggested that because they believed citizens had natural rights independent of the state, then the government could be legitimately challenged, particularly if it was based on non-natural rights such as privilege.

The Enlightenment changed the way that people viewed the relationship between the government and citizen with the idea that people possessed "natural" rights. The concept of natural rights is usually contrasted with the concept of legal rights. Legal rights are those bestowed onto a person by a given legal system (i.e., rights that can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws). Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government; this makes them universal and inalienable (i.e., rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws).

The idea of natural rights is also closely related to that of human rights; some acknowledge no difference between the two, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate the association of human rights with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. This may be because natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dismiss.

The concept of natural rights has been used by radicals as a legitimisation of their overthrow of governments. Revolutionaries in France and the United States were able to claim that because citizens had inalienable rights, a desire to change to a government that better protected these rights was also legitimate. Both the US Declaration of Independence (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789) made specific mention of natural rights.

During the Enlightenment, absolutists believed the state should be able to override certain individual rights in the interests of control and security for all. Liberal thinkers believed that individuals should be protected from excessive state interference in their rights, particularly their civil rights. Civil rights came to be seen as synonymous with natural rights, while other rights, non-universal ones, were considered political rights.

The Enlightenment made progress towards bringing clarity regarding defining rights and what they entail and, to a limited extent, guaranteeing an equality of rights to all. However, there was still much room for improvement, and still many debates to come as to what exactly constitutes a right and how those rights might be best protected—prickly problems that continue to challenge governments and international bodies even today.

Humanitarian Law: Understanding Legal Frameworks for Crisis Response

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Natural rights are those that are universal and inalienable, not dependent on the laws, customs, or beliefs of any particular culture or government. Legal rights, on the other hand, are bestowed onto a person by a given legal system and can be modified, repealed, or restrained by human laws.

During the Enlightenment, the concept of natural law was used to challenge the divine right of kings and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government in the form of classical republicanism. It was also used by others to challenge the legitimacy of all such establishments.

Examples of natural rights include the right to life, liberty, equality, property, justice, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom from slavery.