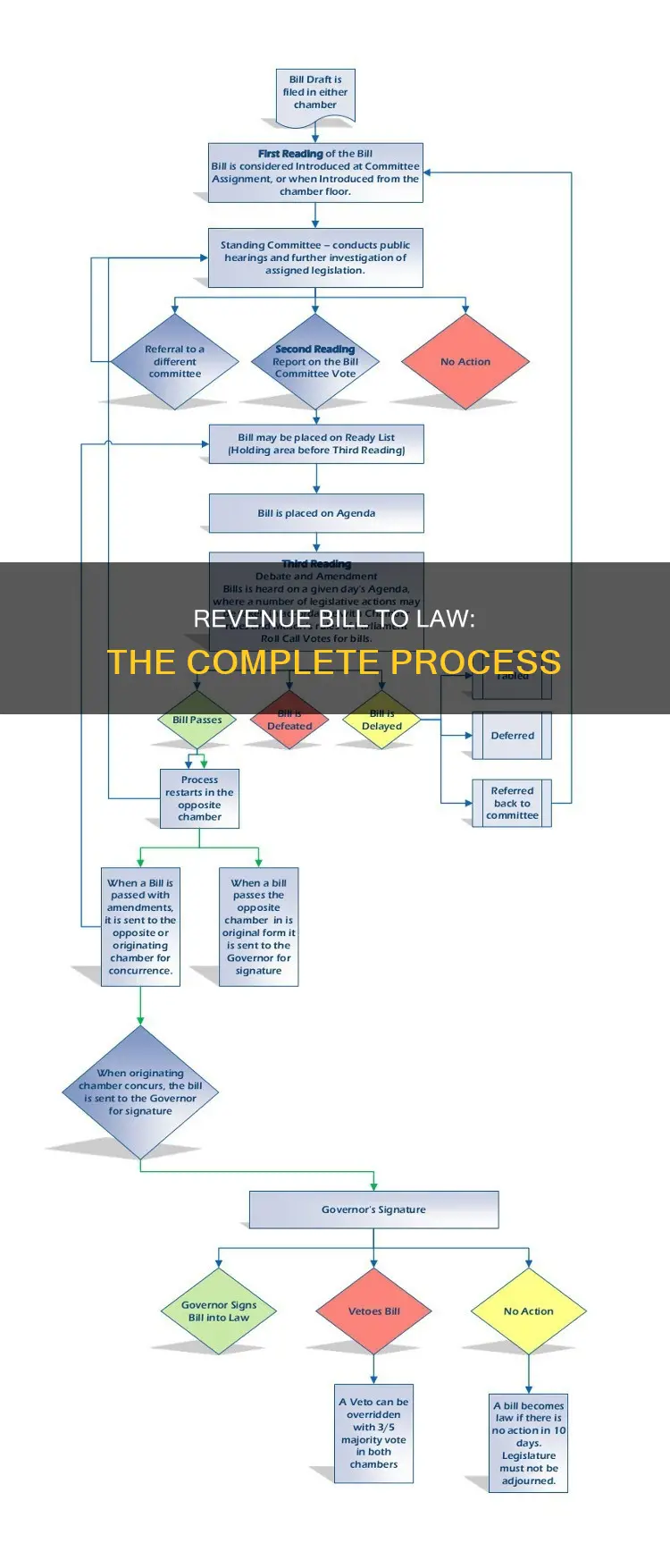

The process of a revenue bill becoming a law is a multi-step procedure that involves the US Congress and the President. The idea for a bill can come from a sitting member of the US Senate or House of Representatives, or be proposed during their election campaign. Once a bill is introduced, it is assigned to a committee, which will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill. The bill is then put before that chamber to be voted on. If the bill passes one body of Congress, it goes through a similar process in the other body. Once both bodies vote to accept a bill, they must work out any differences between the two versions. Then, both chambers vote on the same version of the bill. If it passes, they present it to the President. The President can approve the bill and sign it into law, or they can refuse to approve it, which is called a veto. If the President chooses to veto a bill, Congress can vote to override that veto, and the bill becomes a law. However, if the President does not sign off on a bill and it remains unsigned when Congress is no longer in session, the bill will be vetoed by default, which is called a pocket veto, and cannot be overridden by Congress.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Where a revenue bill is introduced | House of Representatives |

| Who can propose a revenue bill | A sitting member of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives |

| Who can propose a revenue bill | People or citizen groups who recommend a new or amended law to a member of Congress that represents them |

| What happens once a revenue bill is introduced | Assigned to a committee whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill |

| What happens after the committee stage | Put before the chamber to be voted on |

| What happens if the bill passes one body of Congress | It goes to the other body to go through a similar process of research, discussion, changes, and voting |

| What happens once both bodies vote to accept a bill | Work out any differences between the two versions, then both chambers vote on the same version of the bill |

| What happens if the bill passes both chambers | Present it to the president |

| What can the president do | Approve the bill and sign it into law, or refuse to approve a bill (veto) |

| What happens if the president chooses to veto a bill | Congress can vote to override that veto and the bill becomes a law |

| What happens if the president does not sign off on a bill and it remains unsigned when Congress is no longer in session | The bill will be vetoed by default (pocket veto) |

What You'll Learn

All revenue bills must originate in the House of Representatives

The process of a revenue bill becoming a law in the United States begins with its introduction in the House of Representatives. This is a constitutionally mandated step, as the Origination Clause of the US Constitution states that "All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives".

The Origination Clause ensures that persons elected directly by the people have initial responsibility over tax decisions. Before the Seventeenth Amendment was ratified in 1913, only members of the House of Representatives were elected directly by the people.

Once introduced in the House, a revenue bill is sent to a House committee to be examined and debated by specialists. Following committee approval, the bill is then debated on the House floor, where members vote on it. It then moves to the Rules Committee, which determines the debate guidelines.

After passing in the House, the bill is sent to the Senate, where it undergoes a similar process. If the Senate passes its own version of the bill, with differences from the House version, both versions are sent to a conference committee to be reconciled. This reconciled bill is then passed by both houses in identical form, through a majority vote, before being presented to the President for approval.

The President can approve the bill and sign it into law, or veto it. If vetoed, Congress can vote to override the veto, and the bill becomes a law. However, if the President does not sign off on a bill and Congress is no longer in session, the bill is vetoed by default, known as a "pocket veto", which cannot be overridden by Congress.

The Legislative Journey: Bill to Law in Mexico

You may want to see also

The Senate can propose amendments

The process of a revenue bill becoming a law in the United States involves several steps, with the bill passing through the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the President. While the House has the sole power to initiate revenue-related bills, the Senate plays a crucial role in this process by proposing amendments.

The Senate's ability to propose amendments to revenue bills is a significant aspect of lawmaking. The Senate may propose changes to a revenue bill that originated in the House of Representatives. This power of the Senate is explicitly stated in the United States Constitution, specifically in Article I, Section 7, Clause 1, also known as the Origination Clause. The clause states, "All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills." This clause ensures that the Senate has a say in shaping revenue-related legislation, even though it cannot initiate such bills itself.

The Senate's power to propose amendments is not limited to minor changes but extends to substantial modifications. For example, in the case of Flint v. Stone Tracy Co., the Senate amended a House-originated bill by substituting a corporate tax for an inheritance tax. The Supreme Court upheld this amendment, setting a precedent for the Senate's ability to make significant changes to revenue bills.

The Senate's role in proposing amendments is an essential part of the legislative process. It allows for further deliberation and debate on the specifics of a revenue bill, ensuring that it is thoroughly vetted before becoming law. This back-and-forth between the House and the Senate helps to create a stable equilibrium that has been generally well-received.

It is worth noting that the Senate's power to amend revenue bills has reduced the practical significance of the Origination Clause. While the clause was a point of contention during the Constitutional Convention and ratification debates, the Senate's ability to propose amendments has lessened its impact.

Understanding the Legislative Process: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

The bill must pass both bodies of Congress

For a revenue bill to become a law, it must pass both bodies of Congress. This is because the Origination Clause of the US Constitution, specifically Article I, Section 7, Clause 1, states that "All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives". This means that any bill that levies taxes must first be introduced in the House of Representatives.

Once a revenue bill is introduced in the House, it is assigned to a committee whose members will research, discuss, and make changes to the bill. The bill is then put before the House to be voted on. If it passes, the bill then goes through a similar process in the other body of Congress, the Senate. The Senate can propose amendments to the bill, but it cannot originate revenue bills.

If the bill passes the Senate, the two bodies must work out any differences between their versions of the bill. This is done by sending the bill to a conference committee, which reconciles the differences. Once both bodies have agreed on a final bill, they vote on it again. If it passes this final vote, the bill is then presented to the President.

The process of passing a revenue bill through both bodies of Congress is crucial for the bill's progression. It ensures that any legislation involving taxes is first introduced by representatives who are directly elected by the people, giving them initial responsibility over tax decisions.

Becoming a Law Student: Steps to Success

You may want to see also

The president must sign the bill into law

The president's role in signing a revenue bill into law is a critical step in the legislative process. Once a revenue bill has been introduced in the House, passed by both chambers of Congress, and reconciled by the conference committee, it is presented to the president for approval. The president has the power to approve or veto the bill. If the president approves the bill, they sign it into law.

The process of the president signing a bill into law is outlined in Article I, Section 7, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution, also known as the Origination Clause. This clause specifies that all revenue bills must originate in the House of Representatives and, if passed by both chambers of Congress, must be presented to the president for approval. The president has the option to approve the bill and sign it into law or to veto it.

When the president receives a revenue bill, they have the option to approve it and sign it into law. By signing the bill, the president gives their consent, and the bill officially becomes a law. The physical act of signing the bill is a symbolic and important final step in the legislative process. It represents the executive branch's agreement with the legislation and marks the conclusion of the law-making process.

The president is not restricted to signing a bill into law only when Congress is in session. They have the flexibility to sign the bill within ten days, excluding Sundays, even if this period extends beyond the final adjournment of Congress. This provision ensures that the president has adequate time to consider the bill and make an informed decision.

In conclusion, the president's signature on a revenue bill transforms it into law. This step is a crucial part of the checks and balances within the U.S. government, providing an opportunity for the executive branch to weigh in on legislation and either approve or reject it. The president's signature finalises the law-making process and officially establishes the bill as a law of the land.

Law Study: A Must for Aspiring Diplomats?

You may want to see also

Congress can override a veto

The US Constitution gives the President the power to veto acts of Congress to prevent the legislative branch from becoming too powerful. This is an illustration of the separation of powers integral to the US Constitution. By separating the powers of government into three branches and creating a system of "checks and balances" between them, the Framers hoped to prevent the misuse or abuse of power.

The veto allows the President to "check" the legislature by reviewing acts passed by Congress and blocking measures he finds unconstitutional, unjust, or unwise. Congress's power to override the President's veto forms a "balance" between the branches on the lawmaking power.

If the President chooses to veto a bill, in most cases, Congress can vote to override that veto and the bill becomes a law. A two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate is required to override a presidential veto.

The process of overriding a veto is as follows:

- The President vetoes a bill and returns it to the House of Representatives, where it originated, along with a statement of his objections.

- The House of Representatives enters the President's objections into their journal and proceeds to reconsider the bill.

- If, after reconsideration, two-thirds of the House of Representatives agree to pass the bill, it is sent to the Senate, along with the President's objections.

- The Senate then reconsiders the bill, and if approved by two-thirds of the Senate, it becomes a law, notwithstanding the President's veto.

The Legislative Process: A Comic Strip Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

All bills for raising revenue must originate in the House of Representatives. This is known as the Origination Clause.

The bill is sent to a House committee to be examined and debated upon by specialists. Following committee approval, it is then debated on the House floor, where members vote on it. It then moves to the Rules Committee, which determines the debate guidelines.

The bill is sent to the Senate, where it undergoes a similar series of steps. If the Senate passes its own version of the bill, and there are differences compared to the House's version, two versions are sent to the conference committee to reconcile those differences.

The reconciled bill then has to be passed by both houses in identical form, which is done by obtaining a majority vote of both houses. Finally, the approved bill is sent to the President for signing into law or vetoing.