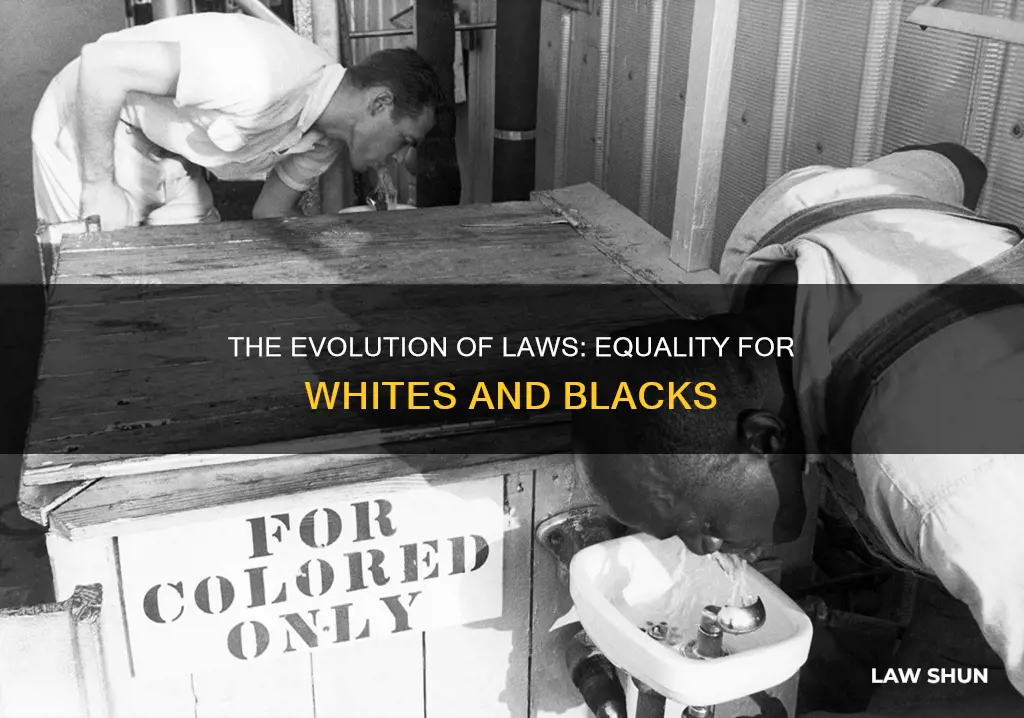

The history of laws applying to both whites and Blacks in the United States is complex and fraught with racial discrimination and segregation. After the Civil War ended in 1865, some states passed Black Codes that severely limited the rights of Black people, including their job opportunities and property ownership. The Reconstruction Act of 1867 weakened these laws by requiring all states to uphold equal protection under the 14th Amendment, specifically by enabling Black men to vote. However, Reconstruction ended in 1877, and southern states enacted more discriminatory laws, leading to the Jim Crow Laws which enforced racial segregation in the American South until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. These laws affected almost every aspect of daily life, mandating segregation in schools, parks, libraries, drinking fountains, restrooms, buses, trains, and restaurants. While in legal theory, Blacks received separate but equal treatment, in reality, their facilities were inferior or non-existent. Additionally, Blacks were systematically denied the right to vote through selective application of literacy tests and other racially motivated criteria. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, played a crucial role in challenging these discriminatory laws and advocating for equal rights.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time period | Between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s |

| Affected locations | American South |

| Affected people | Blacks |

| Affected areas of life | Schools, parks, libraries, drinking fountains, restrooms, buses, trains, and restaurants |

| Purpose | To enforce racial segregation |

| Supreme Court ruling | "Separate but equal" facilities for African Americans did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment |

What You'll Learn

- The 1896 Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v Ferguson upheld the 'separate but equal' doctrine

- The 1908 observations of journalist Ray Stannard Baker

- The 1947 Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) pamphlet and Bayard Rustin song, You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow

- The 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v Board of Education of Topeka

- The 1964 Civil Rights Act

The 1896 Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v Ferguson upheld the 'separate but equal' doctrine

The 1896 Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v Ferguson upheld the separate but equal doctrine, which legitimised segregation laws in the American South. The case began in 1892 when Homer Plessy, a mixed-race man, boarded a whites-only train car in New Orleans, in violation of Louisiana's Separate Car Act of 1890. This Act required "equal, but separate" railroad accommodations for white and non-white passengers. Plessy was charged under the Act, and his lawyers argued that the charges should be dismissed on the grounds that the Act was unconstitutional. The request was denied, and the Louisiana Supreme Court upheld this ruling on appeal. Plessy then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In May 1896, the Supreme Court issued a 7-1 decision against Plessy, ruling that the Louisiana law did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Court stated that although the Fourteenth Amendment established the legal equality of whites and blacks, it did not require the elimination of all "distinctions based upon color". The Court gave deference to the power of American state legislatures to make laws regulating health, safety, and morals (the "police power") and to determine the reasonableness of the laws they passed.

The Court reasoned that laws requiring racial separation were within Louisiana's police power and that as long as a law that classified and separated people by their race was a reasonable and good-faith exercise of a state's police power, it did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. The Court gave State legislatures broad discretion to determine the reasonableness of the laws they passed. The Court rejected Plessy's lawyers' arguments that segregation laws inherently implied that black people were inferior, stating that racial prejudice could not be overcome by legislation.

Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenter from the Court's decision. He disagreed with the conclusion that the Louisiana railcar law did not imply that black people were inferior, and he accused the majority of being willfully ignorant on the issue. He pointed out that the Louisiana law contained an exception for "nurses attending children of the other race", which allowed black women who were nannies to white children to be in the white-only train cars. Harlan said that this showed that the Louisiana law allowed black people to be in white-only cars only if it was obvious that they were "social subordinates" or "domestics". In a now-famous passage, Harlan argued that even though white Americans considered themselves superior to other races, the U.S. Constitution was "color-blind" regarding the law and civil rights:

> "The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power... But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law regards man as man, and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved."

The Plessy v Ferguson ruling legitimised state laws establishing "racial" segregation in the South and provided an impetus for further segregation laws. It also legitimised laws in the North requiring "racial" segregation. The ruling basically granted states legislative immunity when dealing with questions of "race", guaranteeing their right to implement racially separate institutions. Despite the pretense of "separate but equal", non-whites always received inferior facilities and treatment, if they received them at all.

Laws Governing Non-International Armed Conflict

You may want to see also

The 1908 observations of journalist Ray Stannard Baker

In 1908, journalist Ray Stannard Baker made observations about the racial divide in the United States, specifically regarding the Jim Crow laws that upheld racial segregation in the country. Baker, a leading national journalist known for his muckraking articles and belief in social reform, published the book "Following the Color Line: An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy" in 1908. The book explored the situation of Black Americans and the state of race relations in the country.

Baker's observations in 1908 specifically highlighted the impact of the Jim Crow laws on bus travel in the South. He noted that "no other point of race contact is so much and so bitterly discussed among Negroes as the Jim Crow car." This referred to the segregation of buses, trains, and trolley cars that required Blacks and whites to sit separately. This form of transit segregation was a core component of the Jim Crow system, which aimed to prevent any contact between Blacks and whites as equals.

Baker's book "Following the Color Line" was published after the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, which sparked his interest in examining America's racial divide. It became a highly successful and influential work, with sociologist Rupert Vance describing it as "the best account of race relations in the South during the period." The book provided a realistic portrayal of Negro town life and offered insights into the optimism inspired by the Washingtonian movement among liberals and moderates.

Through his observations and writings, Ray Stannard Baker brought attention to the humiliating and dehumanizing impact of the Jim Crow laws on Black people. His work contributed to the growing recognition of the need for social reform and the eventual civil rights movement, which sought to challenge and dismantle the systemic racial segregation in the United States.

A Nestam for the Future: YSR Law Application Guide

You may want to see also

The 1947 Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) pamphlet and Bayard Rustin song, You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow

The 1947 Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) pamphlet and Bayard Rustin's song "You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow" were powerful tools in the fight against racial segregation in the American South. CORE, founded in 1942 by an interracial group of students in Chicago, dedicated itself to the use of nonviolent direct action to challenge segregation. One of their early victories was achieved through sit-ins and other nonviolent tactics to integrate Chicago restaurants and businesses.

In 1947, CORE took their activism to the South with the "Journey of Reconciliation", a multi-state integrated bus ride to challenge segregation in interstate travel. This journey, which included Bayard Rustin, was the first "Freedom Ride", and served as a precursor to the more famous 1961 Freedom Rides. Rustin, a prominent civil rights activist, wrote and composed "You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow" to inspire and educate people about their rights. The song's lyrics are a powerful testament to the struggle for equal rights:

> "You don't have to ride Jim Crow. No, you don’t have to ride Jim Crow. On June the third, the high court said 'When you ride interstate, Jim Crow is dead' You don’t have to ride Jim Crow."

The date of June 3rd referenced in the song is significant. It marks the day in 1946 when the Supreme Court ruled that a Virginia statute enforcing racial segregation on public vehicles was unconstitutional when applied to interstate travel. This ruling was a crucial step forward, giving legal weight to the protests against segregation.

The CORE pamphlet and Rustin's song were part of a broader strategy to target transit segregation. Keeping whites and blacks separate on buses, trains, and trolley cars was a key component of the Jim Crow system, which enforced racial segregation in all aspects of daily life. By taking a stand against this, CORE and Rustin were striking at the heart of a deeply entrenched system of racial oppression. Their courage and determination inspired many, and their nonviolent tactics influenced leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr.

Child Labor Laws: Under 18 or 21?

You may want to see also

The 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v Board of Education of Topeka

The case was brought by the NAACP on behalf of 13 parents in Topeka, Kansas, who challenged the policy of segregation in the city's schools. The parents attempted to enrol their children in the schools closest to them, which were designated for white students. Each child was refused admission and directed to the African-American schools, which were much further from where they lived.

The case was first argued in December 1952 and reargued in December 1953. On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling, stating that segregation of children in public schools on the basis of race was unconstitutional and deprived minority children of equal educational opportunities. The ruling overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine established in the 1896 Plessy v Ferguson case, which had allowed for separate schools for white and African-American children as long as the facilities were deemed equal.

The Brown v Board of Education case was a significant moment in the civil rights movement and a catalyst for further expansion of civil rights during the 1950s. It took another 10 years for Congress to restore full civil rights to minorities, including protections for the right to vote.

Lemon Law and Recalls: What's the Connection?

You may want to see also

The 1964 Civil Rights Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson on July 2, 1964. It was the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The Act outlawed segregation in businesses such as theatres, restaurants, and hotels, banned discriminatory practices in employment, and ended segregation in public places such as swimming pools, libraries, and public schools. It also strengthened the enforcement of voting rights and the desegregation of schools.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a response to massive resistance to desegregation and the murder of Medgar Evers. In June 1963, President John Kennedy asked Congress for a comprehensive civil rights bill. After Kennedy's assassination in November, President Lyndon Johnson pressed hard, with the support of Roy Wilkins and Clarence Mitchell, to secure the bill's passage the following year.

The Act was not passed without difficulty. In the House of Representatives, opposition bottled up the bill in the House Rules Committee. In the Senate, Southern Democratic opponents attempted to talk the bill to death in a filibuster. However, these obstacles were overcome with the leadership of Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, the support of President Lyndon Johnson, and the efforts of Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois, who convinced enough Republicans to support the bill over Democratic opposition.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended the application of "Jim Crow" laws, which had been upheld by the Supreme Court in the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the Court held that racial segregation purported to be "separate but equal" was constitutional.

Miranda Rights: Do They Apply to Minors?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended legal segregation in the United States.

The Black Codes and Jim Crow Laws.

The Black Codes were passed after the Civil War to limit the voting rights of Black citizens and prevent contact between Black and white citizens in public places. They also restricted the jobs and property Black people could own.