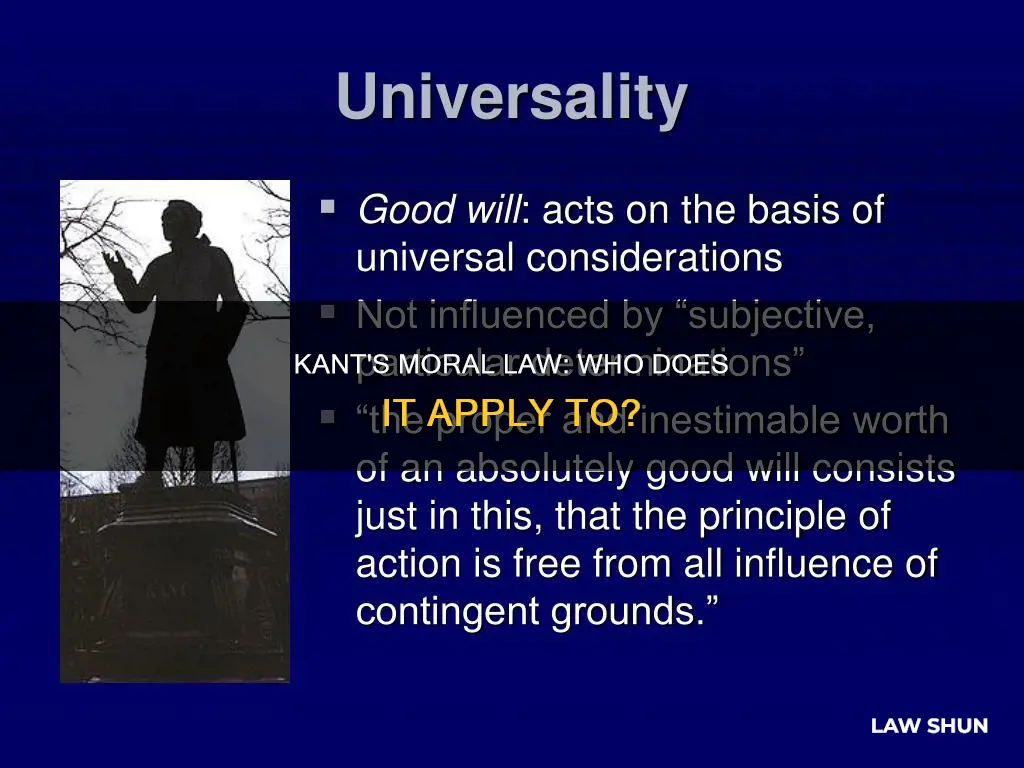

Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy is based on the notion that morality is defined by duties, and an action is moral if it is motivated by duty. Kant calls this the Categorical Imperative, which is a universal ethical principle stating that one should always respect the humanity in others, and that one should only act in accordance with rules that could hold for everyone. This moral law, according to Kant, applies to all rational creatures, and is thus binding for all moral agents without exception.

Kant's Categorical Imperative can be understood through his distinction between hypothetical and categorical imperatives. Hypothetical imperatives are contingent on certain goals or interests, whereas categorical imperatives are necessary and always binding, and determine our moral duties. For example, a hypothetical imperative would be if you want to get a good grade in calculus, work the assignment regularly, whereas a categorical imperative would be do not lie, which binds us regardless of our desires or circumstances.

Kant's moral philosophy focuses on the value of the individual, our ability to reason, and our autonomy. He offers an objective sense of morality through absolute duties that are binding regardless of our desires, goals, or outcomes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Rational creatures | Bound by the same moral law |

| All moral agents without exception | Bound by the moral law |

| All moral agents | Bound by the moral law |

| Persons | Intrinsic moral worth |

What You'll Learn

- The moral law is a truth of reason, and thus binds all rational creatures

- The moral law is not given to us from outside, but is derived from human nature, freedom, and reason

- The moral law is an obligation binding all moral agents without exception

- The moral law is not concerned with the consequences of our actions

- The moral law is based on the notion that I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law

The moral law is a truth of reason, and thus binds all rational creatures

Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy is based on the idea that morality is defined by duties, and an action is moral if it is motivated by duty. Kant calls this the Categorical Imperative, which is a universal ethical principle stating that one should always respect the humanity in others, and that one should only act in accordance with rules that could hold for everyone.

Kant argues that the moral law is a truth of reason, and thus binds all rational creatures. This is because the moral law is nothing other than rational will—the will which is entirely "devoted" to, or guided by impartiality and universality of reason. The nature of reason itself is universal, as is evident in logic, mathematics, and science.

Kant makes a distinction between two types of imperatives: categorical and hypothetical. A hypothetical imperative tells you what to do in order to achieve a goal, but it doesn't tell you what to do if you don't care about that goal. For example, "if you want to get a good grade in calculus, work the assignment regularly." A categorical imperative, on the other hand, tells you how to act regardless of what end or goal you might desire. For instance, "you ought to follow this Categorical Imperative no matter what wants you might happen to have." Categorical imperatives are thus morally binding because they are based on reason, rather than contingent facts about an agent.

Kant's first formulation of the Categorical Imperative is that of universalizability:

> Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.

Kant defines a maxim as a "subjective principle of volition", which is a practical rule that reason determines in accordance with the conditions of the subject (their ignorance or inclinations). A maxim may be a practical law, but it is always the principle that the person themselves act from. Maxims become mere subjectivity and thus unable to qualify as practical laws if they produce a contradiction in conception or a contradiction in the will when universalized.

Kant's second formulation of the Categorical Imperative is to treat humanity as an end in itself:

> So act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.

Kant argued that rational beings can never be treated merely as means to ends; they must always also be treated as ends in themselves, requiring that their own reasoned motives be equally respected. This is because moral obligation is a rational necessity: that which is rationally willed is morally right.

Kant's third formulation of the Categorical Imperative is the Kingdom of Ends:

> A rational being belongs as a member to the kingdom of ends when he gives universal laws in it but is also himself subject to these laws.

This formulation requires that actions be considered as if their maxim is to provide a law for a hypothetical kingdom of Ends. Accordingly, people have an obligation to act upon principles that a community of rational agents would accept as laws. In such a community, each individual would only accept maxims that can govern every member of the community without treating any member merely as a means to an end.

Kant's moral philosophy focuses on fairness and the value of the individual. His method rests on our ability to reason, our autonomy, and logical consistency. He also offers an objective sense of morality in the form of absolute duties—duties that are binding regardless of our desires, goals, or outcomes.

Lemon Law and Salvage Cars: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

The moral law is not given to us from outside, but is derived from human nature, freedom, and reason

Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy is based on the idea that morality is not defined by the consequences of our actions, our emotions, or any external factor. Instead, morality is defined by duties, and an action is moral if it is motivated by duty. The moral law, according to Kant, is not given to us from outside, but is derived from human nature, freedom, and reason. It is a truth of reason, and thus all rational creatures are bound by the same moral law.

Kant's ethics are centred on the notion of a "categorical imperative", which is a universal ethical principle stating that one should always respect the humanity in others and act in accordance with rules that could hold for everyone. The categorical imperative is not meant to be understood as separate duties but rather as different articulations of a single moral duty. Kant provides three formulations of the categorical imperative:

- Always act in such a way that you could will that the maxim of your act become a universal law. This is the requirement of universalizability, meaning that everyone could act the same way.

- Always act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in yourself or others, as an end in itself and never merely as a means. This is the requirement of human dignity, meaning that we should not just use people.

- Always act in such a way that you are both legislator and legislated in the kingdom of "ends". This is the requirement of reciprocity, meaning that your action would be considered fair from all perspectives.

Kant's moral philosophy focuses on fairness and the value of the individual. It rests on our ability to reason, our autonomy, and logical consistency. He offers an objective sense of morality in the form of absolute duties that are binding regardless of our desires, goals, or outcomes.

Kant argues that the only thing that is good in itself is the "good will". The will drives our actions and grounds the intention of our act. It is good when it acts from duty. The will is a good will provided it acts from duty, not just in conformity with duty. This is because it is difficult to determine one's intentions, and acting from duty means understanding one's moral obligation and acting accordingly.

Kant's conception of duty does not entail that people perform their duties grudgingly. Although duty often constrains people and prompts them to act against their inclinations, it still comes from an agent's volition as they desire to keep the moral law from respect for the moral law. Thus, when an agent performs an action from duty, it is because their moral incentives are chosen over and above any opposing inclinations.

Kant wished to move beyond the conception of morality as externally imposed duties and present an ethics of autonomy, where rational agents freely recognize the claims reason makes upon them. He based his ethical theory on the Enlightenment belief that reason should be used to determine how people ought to act, instructing that reason should be used to determine how to behave rather than prescribing specific actions.

Applying to Law School: 3 or 4 Applications Enough?

You may want to see also

The moral law is an obligation binding all moral agents without exception

Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy is based on the notion that "I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law". This is known as the Categorical Imperative, which is Kant's term for the moral law.

The Categorical Imperative is an obligation binding all moral agents without exception. Kant's ethical theory is deontological, meaning that morality is defined by duties, and one's action is moral if it is an act motivated by duty. The moral law is not given to us from the outside, such as through God's command, civil law, or societal recommendation. Instead, it is found within us, in our human nature, freedom, and reason.

Kant identifies the will as what drives our actions and grounds the intention of our acts. The will is good when it acts from duty, and it is the only thing that is intrinsically valuable. Other goods, such as knowledge or courage, can be used for immoral ends, so they are only instrumentally good.

Kant distinguishes between acting in conformity with duty and acting from duty. For example, a person may help an elderly woman across the street because they feel guilty if they don't, or because they want to be rewarded. However, acting from duty means understanding that one has a moral obligation to help others in need.

Kant also distinguishes between hypothetical and categorical imperatives. Hypothetical imperatives are the 'oughts' that direct our actions provided we have certain goals or interests. Categorical imperatives, on the other hand, are necessary and always binding. They are the 'oughts' that determine our moral duties, even if we don't want to fulfil them.

Kant provides three formulas for the Categorical Imperative:

- Universalizability: We ought to act in a way such that the maxim of our act can be willed as a universal law. For example, stealing is morally off-limits because if everyone stole all the time, there would be no private property and stealing would no longer be possible.

- Humanity as an End: We ought to treat humanity (ourselves and others) as an end in itself and never merely as a means. This is based on the idea that humans have the capacity for autonomy and rationality, so we must treat humans with respect and dignity.

- Kingdom of Ends: We ought to act on principles that could be accepted within a community of other rational agents. This moves us from the individual level to the social level, where we are both legislators and legislated in the kingdom of ends.

In summary, Kant's moral philosophy focuses on fairness and the value of the individual. It rests on our ability to reason, our autonomy, and logical consistency. It offers an objective sense of morality through absolute duties that are binding regardless of our desires, goals, or outcomes.

Natural Law Theory's Take on the Trolley Problem

You may want to see also

The moral law is not concerned with the consequences of our actions

Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy is based on the notion that "I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law". This is known as the Categorical Imperative, which is Kant's term for the moral law.

Kant's moral philosophy is deontological, meaning that morality is defined by duties, and one's action is moral if it is an act motivated by duty. The moral law is not concerned with the consequences of our actions, our emotions, or an external factor. Instead, it is defined by duties and is concerned with the intention behind the action.

The moral law is given by reason and is based on the belief that reason should be used to determine how people ought to act. It is not something that is given to us from the outside, such as what God commands or what civil law or society recommends. Rather, it is the rational will—the will that is entirely devoted to, or guided by, impartiality and universality of reason.

The test of the moral law is that it can be universalized, or willed to become a universal law. This is what the Categorical Imperative is for—to provide a way to examine the rationality and therefore moral acceptability of an action.

The moral law is concerned with the intention behind the action, not the consequences. This is because the consequences of our actions are not under our control, whereas our will is. Thus, we cannot be held morally responsible for the consequences of our actions, but we can be held responsible for our will and the intention behind our actions.

Kant's moral theory is often referred to as the "respect for persons" theory of morality. This is because persons, conceived of as autonomous rational moral agents, are beings that have intrinsic moral worth, and this value makes them deserving of moral respect.

Kant's moral theory has three formulas for the Categorical Imperative:

- We ought to act in a way such that the maxim, or principle, of our act can be willed as a universal law.

- We ought to treat humanity (self and others) as an end in itself and never as a mere means.

- We ought to act on principles that could be accepted within a community of other rational agents.

These three formulas are not meant to be understood as separate duties but rather as different articulations of a single moral duty—the Categorical Imperative.

Levitical Law: Still Relevant or Archaic Today?

You may want to see also

The moral law is based on the notion that I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law

Immanuel Kant's moral philosophy is based on the notion that "I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law". This is known as the Categorical Imperative, which is Kant's term for the moral law.

The Categorical Imperative is a universal ethical principle stating that one should always respect the humanity in others, and that one should only act in accordance with rules that could hold for everyone. It is an objective sense of morality in the form of absolute duties – duties that are binding regardless of our desires, goals, or outcomes.

Kant's moral theory is deontological, from the Greek word for the science of duties. This means that, for Kant, morality is defined by duties, and an action is moral if it is an act motivated by duty. The will is what drives our actions and grounds the intention of our act. It is good when it acts from duty.

Kant makes a distinction between acting in conformity with duty and acting from duty. Acting in conformity with duty means acting in a way that is driven by some other goal or desire aside from duty itself. Acting from duty means understanding that one has a moral obligation to help others in need when one can.

Kant's Categorical Imperative has three formulations:

- We ought to act in a way such that the maxim, or principle, of our act can be willed as a universal law. If your maxim cannot be universalised, then that act is morally off-limits.

- We ought to treat humanity (self and others) as an end in itself and never as a mere means. This is the requirement of human dignity – we should not just use people.

- We ought to act on principles that could be accepted within a community of other rational agents. This moves us from the individual level to the social level, and is known as the Kingdom of Ends.

Kant's moral philosophy focuses on fairness and the value of the individual. It rests on our ability to reason, our autonomy, and logical consistency.

Kant's moral theory is often referred to as the "respect for persons" theory of morality. Persons, conceived of as autonomous rational moral agents, are beings that have intrinsic moral worth. This value of persons makes them deserving of moral respect.

Applying Corn Laws: Amino Acid Focus

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The moral law applies to all rational creatures.

The moral law is the sense of obligation that our will often responds to. It is deeper than conscience, which can be mistaken, and is the basic structure and drive of human reason that is in each and every person, and that is also the source of human freedom and autonomy.

The test of the moral law is that it can be universalized, i.e., that one can will that it becomes a universal law. This is what the Categorical Imperative is for – to provide a way to examine the rationality and therefore moral acceptability of an action.